"How many hours should I study today?" Millions of students ask themselves this question every day. The answers you get from classmates range from "at least 8 hours" to "2 hours is plenty." Some swear by all-nighters; others claim they barely crack a book. The confusion is understandable—study advice often comes from anecdote rather than evidence. But what does science actually say?

The truth isn't in the middle—it's more nuanced than a simple number. Decades of research on expertise, cognitive limits, and learning efficiency point to a surprising conclusion: most people dramatically overestimate how much productive studying they can do in a day, while underestimating how much quality matters over quantity.

In this article, you'll learn what research says about optimal study times, which factors influence your personal limits, and how to get the most out of your study sessions. Whether you're preparing for final exams, standardized tests, or professional licensing, the principles remain the same—and the evidence is clearer than you might expect.

What does science say about optimal study time?

The 4-hour limit: Deliberate Practice

Psychologist Anders Ericsson, famous for his research on expertise and the "10,000-hour rule," made a surprising discovery that upends conventional wisdom about hard work. Even elite performers—the best in the world at what they do—rarely practice more than 4 hours per day at high intensity. This wasn't due to lack of dedication; it was a biological limit.

The elite violinists averaged 3.5 hours of deliberate practice per day… They practiced with full concentration in sessions lasting no more than 90 minutes, then took breaks.

— Anders Ericsson, Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise

In his landmark study of violinists at the Berlin University of the Arts, Ericsson found that the best performers practiced an average of 3.5 hours per day, divided into two focused blocks—one in the morning, one in the afternoon. Crucially, the elite violinists weren't practicing more than their less accomplished peers; they were practicing better. More than 4 hours led to quality decline and increased injury risk, so they deliberately stopped.

The best performers don't practice longer—they practice smarter, then rest.

What does this mean for studying? Deliberate practice—focused, goal-oriented work with feedback—is mentally exhausting. Your brain simply cannot maintain this state indefinitely. After about 4 hours of true concentration, absorption capacity drops dramatically. The implication is clear: if world-class musicians can't sustain more than 4 hours of peak practice, expecting yourself to productively study for 8 or 10 hours is unrealistic.

Deep Work: Cal Newport's findings

Cal Newport, computer science professor and author of "Deep Work," extends Ericsson's insights into the modern knowledge economy. His research on focused, distraction-free work confirms what the violinists demonstrated: there's a hard ceiling on how much concentrated cognitive work humans can sustain.

The ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy.

— Cal Newport, Deep Work

Newport distinguishes between "Deep Work"—concentrated, distraction-free work that pushes your cognitive capabilities—and "Shallow Work," which includes emails, scheduling, and other tasks that don't require intense focus. The distinction matters because many students conflate the two, counting hours of shallow activity as productive study time.

Through observing himself and other knowledge workers, Newport found that beginners typically manage just 1–2 hours of deep work per day. After 1–2 years of deliberate training in focus, 3–4 hours become possible. But the absolute ceiling remains firm—even seasoned professionals rarely sustain more than 4–5 hours of true deep work.

For a deeper dive into implementing deep work in your study routine, read our guide Deep Work with Athenify.

The diminishing returns curve

If individual limits weren't convincing enough, broader academic research confirms the pattern. Multiple studies have examined the relationship between study hours and academic performance, and the findings are consistent: learning returns per hour drop dramatically beyond a certain threshold.

A study by Nonis & Hudson (2010) surveyed over 1,000 students and found no linear relationship between study time and grades. Students who studied 6 hours didn't consistently outperform those who studied 4 hours. Beyond a certain point, more time simply didn't produce better results. Similarly, Plant et al. (2005) found that the quality of study time—concentration level, study methods used, and engagement with material—was a stronger predictor of academic success than raw hours logged.

After 5–6 hours of concentrated studying, returns diminish so much that you're better off resting.

The core message is counterintuitive but liberating: more isn't always better. Once you've hit your cognitive ceiling for the day, additional hours don't just fail to help—they may actively harm your learning by creating interference and fatigue that undermines consolidation during sleep.

Factors that influence your optimal study time

The "perfect" number of hours doesn't exist as a universal constant. Your individual ceiling depends on several factors that shift throughout the semester and even throughout each day.

1. Type of material

Not every subject places the same cognitive demands on your brain. Understanding complex mathematical proofs requires intense concentration and can only be sustained for 2–3 hours before quality deteriorates. Learning new concepts falls into the high-demand category as well, with most people maxing out around 3–4 hours. Solving practice problems sits in the middle ground—you're applying known concepts rather than building new ones, so 4–5 hours becomes achievable. Lighter activities like reviewing flashcards or reading summaries can extend to 5–6 hours because they require recognition rather than deep processing.

| Study Activity | Cognitive Load | Max Focus Time |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding complex proofs | Very high | 2–3 h |

| Learning new concepts | High | 3–4 h |

| Solving practice problems | Medium | 4–5 h |

| Reviewing flashcards | Low | 5–6 h |

| Reading summaries | Low | 5–6 h |

2. Time until your exam

The closer the exam, the more you can—and likely will—study, but only to a point. When you're 3+ months out, 2–3 hours per day is sustainable and prevents burnout. As you move into the 1–3 month window, 4–5 hours daily becomes manageable. During the final weeks, 5–6 hours is achievable with careful attention to rest. But in the final days before the exam, less is more. Your brain needs time to consolidate what you've learned, not cram in more information.

3. Your personal chronotype

Are you a lark or an owl? Your chronotype—your natural preference for morning or evening activity—profoundly influences when you're most productive. Larks (early risers) typically peak between 8am and noon. Owls (night owls) hit their stride between 4pm and 10pm. Neutral types, representing about 60% of the population, peak somewhere between 10am and 2pm.

The practical implication: schedule your most demanding material during your peak hours, and save lighter review for your natural low points.

4. Your current training state

Like physical exercise, cognitive endurance improves with regular training. If you haven't studied seriously in weeks, don't expect to sustain 6 hours on day one. You'll burn out and likely abandon your efforts entirely. Instead, build up gradually: start with 2 hours, add 30 minutes each week, and let your focus muscles strengthen over time.

Research by Lally et al. found that habits take an average of 66 days to become automatic—about two months before your new study routine starts feeling natural. This means your first two months of a new study routine will feel harder than they eventually will—persistence during this period pays compounding dividends.

Concrete guidelines for different scenarios

Based on research and practical experience, here are specific recommendations for different academic situations. These aren't arbitrary numbers—they're calibrated to maximize learning while respecting cognitive limits.

Regular semester

Recommendation: 2–4 hours per day

During the regular semester, your goal is maintaining consistent progress rather than heroic daily efforts. Quality beats quantity:

- Lecture days: 2–3 hours (lectures consume cognitive resources)

- Free days: 3–4 hours of focused study

- Rest day: One complete day off per week

Exam period

Recommendation: 4–6 hours per day

During intensive exam preparation, you can push harder—but carefully. Plan for 5–6 hours on most days, with 1–2 reduced days of 3–4 hours to allow partial recovery. Even in the thick of exam season, preserve at least one half rest day per week. Your brain consolidates learning during rest, so skipping recovery actually undermines the hours you put in. For detailed strategies on structuring your exam prep, see our exam preparation guide.

Exam period is a sprint within a marathon. Push hard, but don't burn out.

Standardized test prep (SAT, LSAT, MCAT)

Recommendation: 2–4 hours per day over months

Standardized test preparation is a different beast entirely. Unlike course exams where you're mastering defined content, standardized tests require developing skills that improve gradually over time. You're training pattern recognition, timing intuition, and strategic thinking—none of which can be crammed.

| Test | Daily Study | Duration | Total Hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAT | 1–2 h | 2–4 months | 40–200 h |

| LSAT | 2–4 h | 4–6 months | 250–400 h |

| MCAT | 3–6 h | 4–6 months | 300–500 h |

Graduate/professional exams (Bar, Medical Boards)

Recommendation: 6–8 hours per day

Professional licensing exams represent the upper extreme of study intensity. These exams require extraordinary commitment—but even here, hard limits exist. Sustainable bar exam preparation typically involves 6–8 hours on weekdays (Monday through Friday), dropping to 4–5 hours on Saturday. Sundays should be completely off or limited to 2–3 hours of light review. And critically, plan for a full recovery week every 4–6 weeks, with a maximum of 2 hours per day.

The students who burn out during bar prep aren't the ones who took too many rest days—they're the ones who didn't take enough.

Quality vs. quantity: The real question

The number of hours is only half the story. Effective study time matters far more than time at your desk—and the gap between perceived study time and actual productive hours is often enormous.

The problem with gross study time

Many students say: "I was in the library for 8 hours." But how much of that was actual studying? When researchers have tracked this question rigorously, the results are humbling.

Typical breakdown of an 8-hour library day:

- 40–60% – Focused studying (3–5 hours of real study)

- 10–15% – Productive breaks

- 15–25% – Distractions (phone checks, daydreaming, social media)

- 10–20% – Unproductive breaks

The math is sobering: that heroic 8-hour session likely contained only 4–5 hours of real study.

This isn't a moral failing—it's human nature. Our brains aren't designed for uninterrupted focus. The problem arises when we count distracted hours as productive ones, then wonder why our results don't match our "effort."

Net study time is king

This is precisely why time tracking matters. Honest tracking reveals your actual net study time—not the time you spent at your desk, but the time you spent genuinely engaged with material. When students first start tracking their real focus time, they're often shocked to discover they study far less than they thought.

4 hours of true focus time beats 8 hours of half-hearted "studying"—every time.

The good news? Once you know your real numbers, you can improve them. And 4 focused hours, honestly tracked, will outperform 8 distracted ones. For more on the science behind effective study time, read our article The Science Behind Study Time Tracking, or explore our comprehensive guide to study time tracking for practical implementation strategies.

How Athenify helps you find your optimal study time

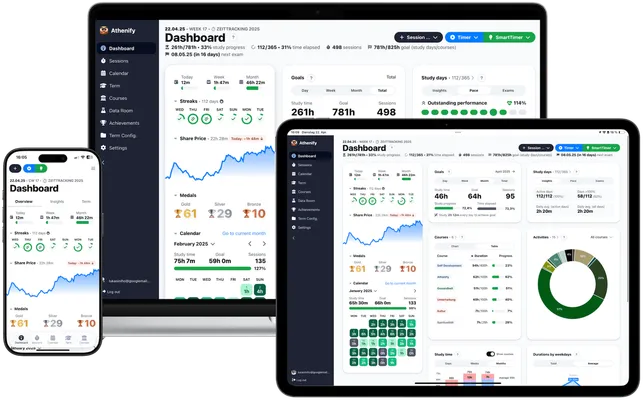

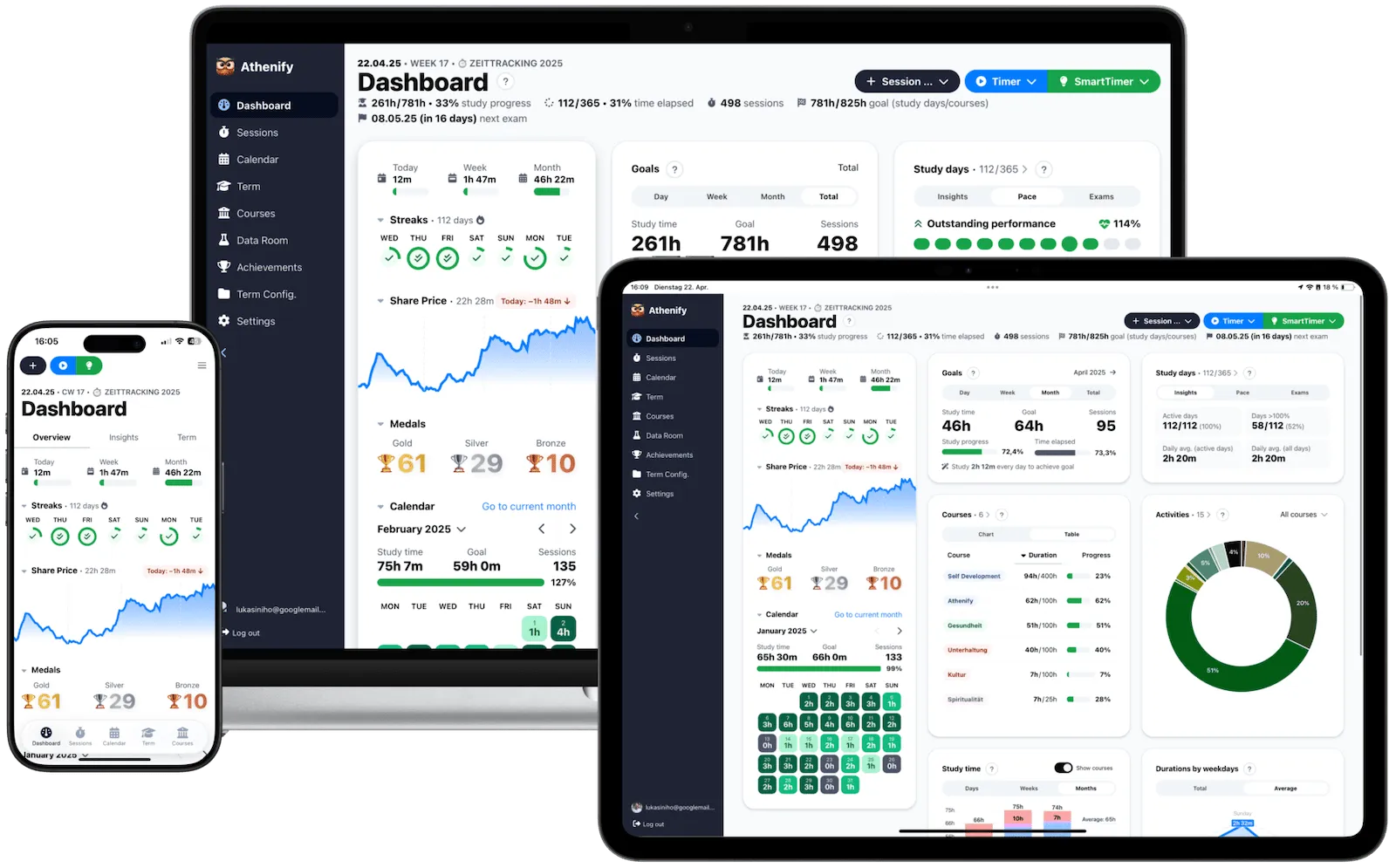

Athenify was designed to answer exactly this question: How much am I actually studying—and how can I optimize? Rather than guessing or relying on intuition, Athenify provides the data you need to discover your personal limits.

Honest time tracking with the focus timer

The fullscreen focus timer measures only the time you're actually studying. There's no room for self-deception: the timer only runs when you're active, pausing when you pause. Fullscreen mode automatically reduces distractions by hiding notifications and other apps. And every session gets logged, so you can see exactly when you studied and for how long.

Set and check daily goals

Athenify lets you define your daily study goal in minutes. The dashboard provides instant feedback: Have you reached your goal? How much is left? What's your trend over recent days? This visibility transforms vague intentions into concrete targets.

The Pomodoro timer for structured blocks

The Pomodoro Timer helps structure your study time into digestible units. The classic format—25 minutes of focus followed by a 5-minute break—works well for many students, but you can adjust the intervals to match your personal rhythm. Automatic break reminders ensure you actually rest, rather than pushing through diminishing returns.

Data-driven self-knowledge

The Dashboard reveals patterns you'd never notice otherwise. You'll see which days of the week you study most (and which you consistently skip), what times of day you're most productive, and which subjects are being neglected. With this data, you can find your optimal study time empirically—through measuring, not guessing.

Try Athenify for free

Track your actual focused hours, discover your peak productivity times, and see the data that reveals your optimal study duration.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Practical tips: Finding your optimal study time

Run a 2-week experiment

The fastest way to discover your personal limits is through systematic self-experimentation. For two weeks, track three things each day: how many hours you studied, how productive you felt on a scale of 1–10, and how much you actually retained (you can test this with quick recall exercises). After two weeks, patterns will emerge. You'll likely find a sweet spot—a number of hours where productivity is high and retention remains strong. Push beyond that, and your numbers will tell you.

The 90-minute block rule

Your brain operates in ultradian rhythms of approximately 90 minutes—natural cycles of higher and lower alertness that repeat throughout the day. Structure your study time to work with these rhythms:

- Focus for 90 minutes on a single task or topic

- Take a 15–20 minute break (movement is ideal; phone scrolling is not)

- Repeat for 3–4 blocks maximum—that's 4.5–6 hours of deep work

- Stop before quality drops—pushing beyond depletes tomorrow's reserves

The energy check

Before each study session, take a moment to rate your energy level on a scale of 1–10. This simple practice prevents you from wasting peak energy on easy tasks—or torturing yourself with difficult material when you're depleted. If you're at 7–10, tackle your most difficult topics. At 4–6, focus on review and practice problems. At 1–3, you're better off taking a real break than forcing unproductive study.

The weekly rhythm

Not every day needs to be the same. In fact, building variation into your week can improve sustainability and results. For help designing an effective weekly structure, see our guide on creating a study schedule. A sensible weekly rhythm:

- Monday–Thursday – Study at full capacity

- Friday – Reduce the load for recovery

- Saturday – Flexible; catch up if needed or take more rest

- Sunday – Completely off or limit to light review

This rhythm respects your need for rest while maintaining momentum.

Conclusion: The answer to "How many hours per day?"

So what's the science-backed answer to the question every student asks? It depends on your situation, but the research points to clear guidelines:

| Scenario | Recommended Study Time | Maximum Focus Time |

|---|---|---|

| Regular semester | 2–4 h/day | 3–4 h deep work |

| Exam period | 4–6 h/day | 4–5 h deep work |

| Intensive test prep | 3–6 h/day | 4–6 h deep work |

| Professional exams | 6–8 h/day | 5–6 h deep work |

The question isn't "How many hours can I study?"—it's "How many hours can I study productively?"

The research is unambiguous on three points. First, quality beats quantity: 4 focused hours produce more learning than 8 unfocused ones, every time. Second, there's a hard upper limit. Even professionals at the top of their fields rarely manage more than 4–6 hours of true deep work per day—and they've spent years building to that capacity. Third, you must track your real study time. Without honest measurement, you'll overestimate your productive hours and underperform relative to your potential. Only through tracking do you see how much you're really studying.

The number of hours matters less than what you do with them. Find your personal ceiling through experimentation, structure your sessions to respect your cognitive limits, and remember that rest is not the opposite of productivity—it's a prerequisite for it.