You track your steps, your sleep, your calories – but what about your study time? While fitness trackers have long become mainstream, systematically tracking study time is still in its infancy for most students. Yet research clearly shows: Those who understand the science behind learning and track their study time learn more effectively.

Effective studying isn't about willpower – it's about applying what decades of cognitive science research has discovered about how we learn best.

In this comprehensive guide, I'll introduce you to 11 evidence-based concepts that explain how to study more effectively according to science. Each concept is backed by peer-reviewed studies – with links to the original sources. You'll learn not just the theory, but also practical ways to apply these principles. You'll discover the optimal times for learning, understand why the simple act of tracking changes behavior, and learn how to build study habits that stick for the long term. For a practical implementation guide, see our comprehensive resource on study time tracking.

1. Best time to study according to science

When is your brain most ready to learn?

One of the most frequently asked questions in learning science is: When is the best time to study? The answer depends on your chronotype and what you're trying to learn, but research provides clear guidance.

According to cognitive science, the brain goes through different states throughout the day:

- 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM – Peak alertness for most people, ideal for analytical tasks, problem-solving, and learning new concepts. Your working memory operates at full capacity.

- 3:00 to 4:00 PM – The infamous "post-lunch dip." Best avoided for complex learning, as your circadian rhythm naturally dips.

- 4:00 PM to 10:00 PM – A second peak of alertness emerges, particularly good for creative tasks and consolidating information you learned earlier.

What does the research say?

The scientific literature strongly supports the importance of timing. Schmidt et al. (2007) published a comprehensive review in Cognitive Neuropsychology titled "A time to think: Circadian rhythms in human cognition," which found that cognitive performance peaks during hours of high circadian arousal – for most people, this means late morning to early afternoon.

Interestingly, age plays a role in optimal timing. May et al. (1993) demonstrated in Psychological Science that older adults perform best in the morning, while younger adults show more flexibility with peak performance often extending into late afternoon. The key finding across both studies: matching study time to your personal peak hours improves performance by up to 20%.

How long should you study per day?

Science also provides guidance on optimal study duration, and the answer might surprise those who pride themselves on marathon study sessions. Dunlosky et al. (2013) published a landmark review in Psychological Science in the Public Interest that found distributed practice – shorter sessions spread over multiple days – consistently outperforms massed practice, those long cramming sessions we've all been guilty of.

The question of session length has also been studied extensively. Research by the Draugiem Group using productivity tracking software discovered that the most productive people work for approximately 52 minutes, then take a 17-minute break. This aligns with multiple studies on the Pomodoro Technique, which confirm that 25–50 minute focused sessions with short breaks optimize both attention and retention. The brain simply isn't designed for hours of uninterrupted focus – it needs periodic recovery to consolidate learning.

2. Metacognition – learning about learning

What is metacognition?

Metacognition refers to awareness of one's own thinking processes and learning strategies. It's about not just learning, but understanding how you learn – and using that knowledge to optimize your learning process.

When you track your study time, you automatically develop metacognitive skills. You start asking questions that previously never crossed your mind: Why did I only manage 45 minutes today? Which subject needs more time? When am I most productive? This self-reflection is the first step toward building better study habits. You transform from a passive learner – someone who simply goes through the motions – into an active pilot of your learning process, constantly adjusting course based on real data rather than vague feelings.

What does the research say?

The research on metacognition is remarkably clear. Wang et al. (1990) demonstrated that students with strong metacognitive skills learn more and perform better than peers who are still developing their metacognition, establishing metacognition as one of the strongest predictors of academic success.

Building on this foundation, Donker et al. (2014) conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of learning strategy interventions and found that metacognitive strategies have a substantial effect on learning outcomes. The strategies that proved particularly effective were those focused on planning, monitoring, and evaluating one's own learning process – exactly the skills that time tracking naturally develops.

Perhaps most compelling is the work of Ohtani & Hisasaka (2018), whose meta-analysis across different developmental stages found that metacognition showed a significant correlation with academic performance (r = 0.36) – even when controlling for intelligence. This finding has profound implications: metacognitive skills are trainable and work independently of IQ, meaning anyone can improve their learning through better self-awareness.

How to apply this

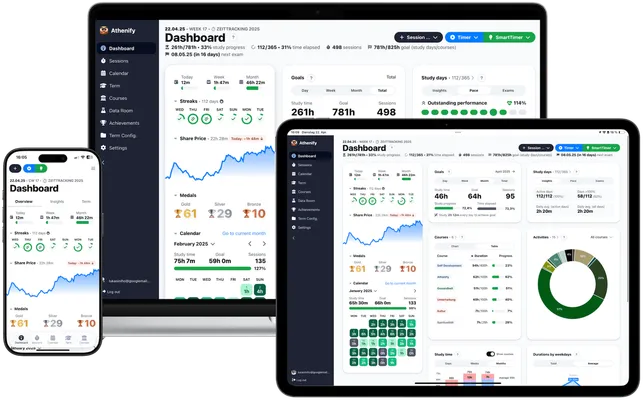

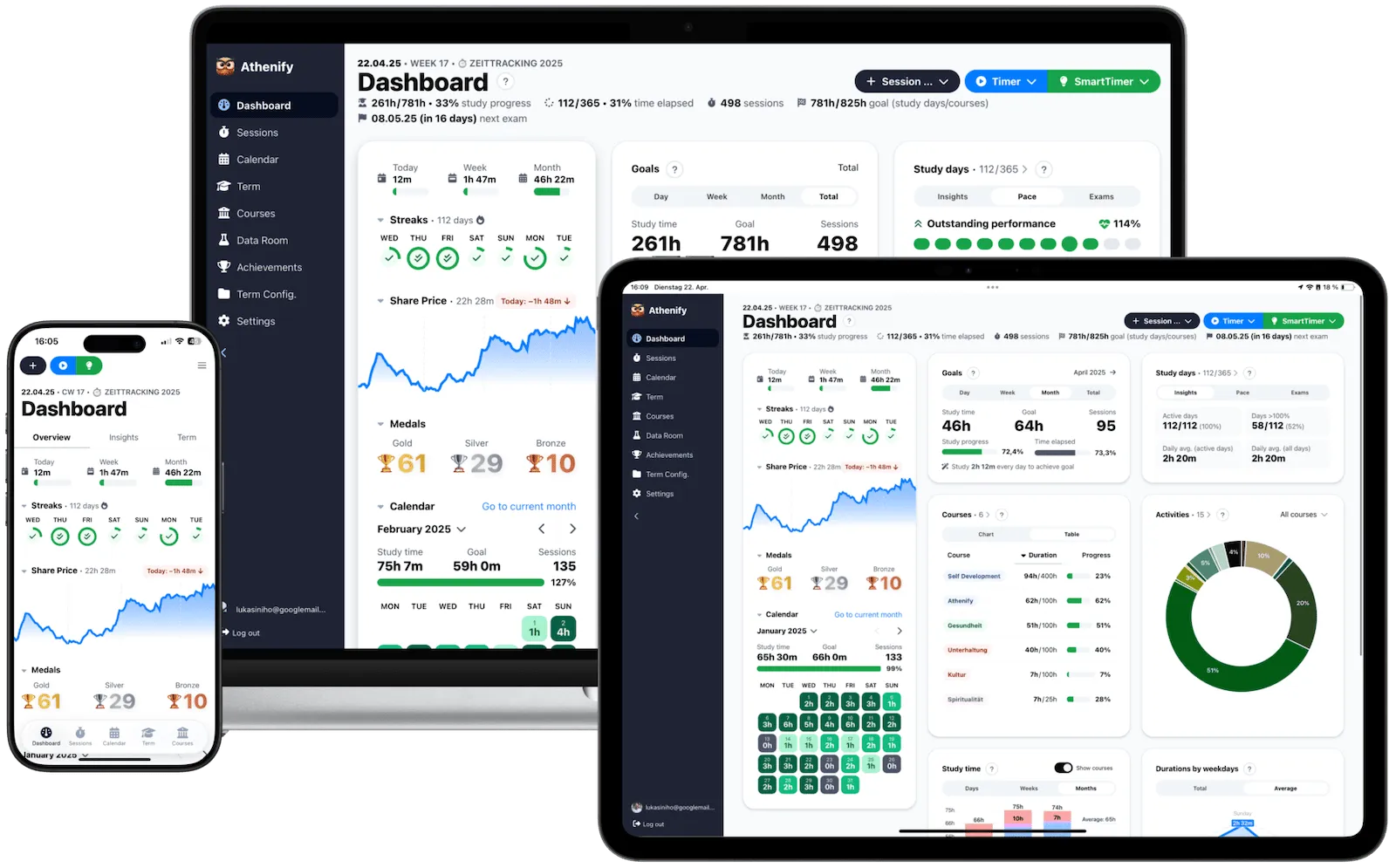

The dashboard in Athenify promotes metacognition on multiple levels. The subject distribution view lets you see at a glance how much time goes into each subject, often revealing surprising imbalances you weren't aware of. Activity analysis shows which learning types – reading, exercises, summaries – you use and how often, helping you identify whether you're spending too much time on passive methods. Time trends reveal when you're most productive, transforming vague intuitions into actionable data. This information forces you to reflect, and that reflection is precisely what trains your metacognition over time.

3. "What gets measured, gets managed" – the power of measurement

The principle explained

"What gets measured, gets managed" – this classic management principle translates directly to learning: Without data about your study time, there's no foundation for targeted optimization.

The principle works in both directions. First, visibility creates action: what you measure, you consciously perceive – and can therefore change. Second, data enables optimization, because without a baseline, there's no foundation for improvement. You can't optimize what you can't see.

Many students have only a vague sense of how much they study. They think they've been studying "all day," when the actual net study time was perhaps 2–3 hours. Research suggests students overestimate their effective study time by 30–40% on average. Only through measurement does this blind spot become visible.

You can't optimize what you can't see. Measurement is the first step toward meaningful improvement.

Scientific background

The foundation of this principle traces back to Drucker (1954) and his classic "The Practice of Management," where he wrote: "Work implies accountability, a deadline and the measurement of results – feedback from results on the work and planning process itself." Measuring results is fundamental to improvement, whether in business or learning.

However, measurement isn't without its pitfalls. Ridgway (1956) published "Dysfunctional Consequences of Performance Measurements" in Administrative Science Quarterly, warning of the dangers of blind measurement – but also recognizing its benefits when applied correctly. The message is nuanced: measure the right things, not everything. For studying, this means tracking subject, activity, and time – enough to make informed decisions without getting lost in a data jungle.

How to apply this

Athenify makes measuring effortless. The automatic tracking captures every minute through a simple timer interface, eliminating the friction of manual logging. Clear statistics present your data in daily, weekly, and semester views, allowing you to zoom in on recent patterns or zoom out for long-term trends. The Share Price feature visualizes your cumulative over- or under-achievement relative to your goals, giving you an instant read on where you stand.

4. Self-monitoring – the reactivity of measurement

The phenomenon of reactivity

Self-monitoring refers to systematically observing one's own behavior. Psychological research reveals a fascinating phenomenon: Simply observing a behavior changes that behavior – the so-called reactivity of measurement.

This means: When you know you're tracking your study time, you automatically study more and with more focus. The running timer becomes a gentle reminder to stay on task.

What does the research show?

The effectiveness of self-monitoring is well-documented across decades of research. Nelson & Hayes (1981) published an influential study in Behavior Modification showing that merely recording behaviors changed their frequency. The reactivity was so strong that self-monitoring is now used as a therapeutic intervention in its own right – simply observing yourself is powerful medicine.

This effect holds true in educational settings. Mace & Kratochwill (1985) found that among students, all self-monitoring conditions led to significant behavioral changes. Remarkably, mere recording – without any external reward or punishment – proved effective. The act of observation itself was sufficient to drive improvement.

The most compelling evidence comes from Harkin et al. (2016), who conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis across 138 studies with nearly 20,000 participants. They confirmed that progress monitoring significantly improves goal attainment, with an effect size of d = 0.40. This principle works across domains, from health to learning to work performance.

How to apply this

The fullscreen focus timer optimally utilizes the reactivity effect. The visible time measurement means you see every second that passes, creating a constant awareness of your studying. Once started, the timer creates a commitment effect – a sense of obligation to continue that makes it harder to give up. And because every session is saved, you build documentation that shows you later what you accomplished, reinforcing the cycle of awareness and improvement.

Streaks also leverage self-monitoring brilliantly. You see daily whether you reached your study goal, and that visible record motivates you to keep going. Breaking a streak feels like a loss, which taps into loss aversion – one of the most powerful forces in human psychology.

5. Goal-setting theory – the power of specific goals

What does goal-setting theory state?

The Goal-Setting Theory by Edwin Locke and Gary Latham is one of the most thoroughly researched motivation theories. Its core message: Specific, challenging goals lead to better performance than vague intentions or no goals at all.

The most effective performance occurs when goals are specific and challenging, when they are used to evaluate performance, and when there is feedback on performance.

— Edwin Locke & Gary Latham, A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance

"I want to study today" isn't a goal – it's an intention. "I want to study statistics for 3 hours today" is a goal. The difference is measurable: Specific goals lead to 10-25% better performance than vague goals.

Tracking enables setting and verifying concrete study goals. Without data, you don't know if you've reached your goal. With data, goal attainment is binary: achieved or not.

The research base

The evidence for goal-setting theory is overwhelming. Locke & Latham (2006) published a comprehensive review titled "New Directions in Goal-Setting Theory" that summarizes 40 years of research encompassing approximately 400 laboratory and field studies. Their consistent finding: people with high, specific goals perform better than those with vague goals like "Do your best."

The effect extends specifically to academic settings. Latham & Brown (2006) found that MBAMaster of Business Administration students with specific learning goals had higher GPAGrade Point Averages and reported more satisfaction than those with only distal performance goals. Interestingly, learning goals – "I want to understand how..." – proved more effective than pure outcome goals like "I want to get an A."

More recently, Martin et al. (2016) published a study in Learning and Individual Differences showing that personal best goal-setting led to significant academic achievement gains. The effect was particularly strong for students who tracked their progress, suggesting a synergy between goal-setting and monitoring.

How to apply this

Define daily study goals in minutes for maximum clarity. You immediately see whether you're on track, removing all ambiguity about your progress. The Share Price shows cumulatively whether you're above or below your goal, giving you a long-term perspective that daily views miss. The Medal Table rewards exceeding goals with visible achievements, turning goal-setting from a chore into a game.

6. Feedback loops – the importance of timely feedback

Why feedback is essential

Without feedback, no improvement. Feedback loops are cycles in which you receive information about your behavior and can react to it. The faster and more specific the feedback, the more effective the learning curve.

Feedback is the breakfast of champions. Without knowing how you're doing, you can't improve.

In traditional learning, feedback is very delayed: You study for weeks, take an exam, and find out weeks later how you did. That's too late to adjust the learning process.

Tracking provides continuous feedback – daily, weekly, throughout the semester. You immediately know whether you're studying enough and can adjust course.

What does science say?

The research on feedback is striking. Bandura & Cervone (1983) conducted a classic study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology that demonstrated the power of feedback quantitatively: the group receiving feedback increased their effort by approximately 30% more than the control group, and feedback led to a 25% improvement in task accuracy. These aren't marginal gains – they're transformative.

The educational implications were crystallized by Hattie & Timperley (2007) in their influential review "The Power of Feedback" published in the Review of Educational Research. They found that feedback about performance and understanding enables students to improve their learning significantly. In fact, the effect size of feedback is among the highest in all of educational research – making it one of the most powerful tools available to learners.

How to apply this

The key to effective feedback is getting it at multiple time scales. Immediately, the timer shows you in real-time how long you're studying, creating moment-to-moment awareness. Daily, the dashboard shows your goal attainment, letting you know whether today was a success. Weekly, statistics reveal your most productive days and subjects, helping you plan better. And at the semester level, The Share Price shows the long-term trend, keeping you focused on the bigger picture when individual days feel discouraging.

7. Self-determination theory – autonomy and competence

The three basic psychological needs

Self-Determination Theory (SDTSelf-Determination Theory) by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan is one of the most influential motivation theories. It identifies three innate psychological needs: autonomy (the feeling of making one's own decisions), competence (the feeling of being able to master tasks), and relatedness (the feeling of being connected to others). When these needs are met, intrinsic motivation emerges – you study because you want to, not because you have to.

Tracking, done right, can support all three needs. It fosters autonomy because you decide yourself what and how much you track – no one imposes the system on you. It builds competence because visible progress shows you that you're advancing, providing the mastery experiences humans crave. And while tracking is often a solo activity, gamification elements like streaks and medals create a form of relatedness – an identification with goals that feels almost social.

Research evidence

The theoretical foundation was established by Ryan & Deci (2000) in their highly cited article "Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation" in American Psychologist. They demonstrated that the three basic needs fundamentally influence both intrinsic motivation and overall well-being. Since the 1970s, over 10,000 studies have examined Self-Determination Theory across cultures and contexts.

The educational implications are profound. Grolnick & Ryan (1987) found that students in controlling learning conditions lost initiative and learned less effectively, especially with conceptual learning. Autonomy support proved crucial for deeper learning and engagement – a finding that explains why self-directed tracking works better than mandatory study schedules imposed by others.

On a larger scale, Vallerand et al. (1997) studied over 4,500 high school students and found that perceived autonomy support from teachers and parents predicted self-determined motivation, which in turn affected academic outcomes and persistence. The chain is clear: autonomy leads to motivation leads to success.

How to apply this

Build systems that support your psychological needs across all three dimensions. For autonomy, choose your own subjects, activities, and daily goals – resist the urge to copy someone else's system. For competence, use tools like The Medal Table that make successes visible and celebrate your wins. For relatedness, find a study partner who shares your goals, or use tracking apps as "digital study partners" that create a sense of accountability without external judgment.

8. Habit formation – the 66-day rule

How habits form

Habits follow a simple pattern: Cue → Routine → Reward (Trigger → Behavior → Reward). This cycle, popularized by Charles Duhigg in "The Power of Habit," explains how automatic behavior develops.

Champions don't do extraordinary things. They do ordinary things, but they do them without thinking, too fast for the other team to react. They follow the habits they've learned.

— Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habit

Study time tracking utilizes all three elements of the habit loop:

- Cue – Opening the app or sitting at your desk serves as a consistent trigger that signals "study time."

- Routine – Starting the timer and studying becomes increasingly automatic over time.

- Reward – Watching your streak grow or earning a medal provides the dopamine hit that reinforces the loop.

Streaks are particularly powerful in this context. The "Don't break the chain" principle, famously attributed to Jerry Seinfeld, leverages loss aversion – you don't want to lose what you've built. A 30-day streak feels like an asset, and the thought of resetting to zero creates just enough psychological pressure to get you studying on days when motivation fails. For more strategies on building consistent routines, explore our guide on study habits.

What does research show?

The timeline for habit formation is now well-established. Lally et al. (2010) published the famous study in the European Journal of Social Psychology that found habit formation takes an average of 66 days, with a surprisingly wide range of 18–254 days. Speed varies depending on behavior complexity and individual motivation, meaning some students will lock in their study habit in weeks while others need months.

Habit formation takes 66 days on average – but consistency of context matters more than intensity of effort.

More recent research refines these findings. Keller et al. (2021) found a median of 59 days for successful habit formation in the British Journal of Health Psychology. Importantly, success was more likely with intrinsically rewarding behaviors – like the feeling of having learned something – which suggests that finding genuine satisfaction in studying accelerates habit formation.

Context matters enormously. Stojanovic et al. (2022) published research in Frontiers in Psychology finding that performing behavior in a stable context – same time, same place – was associated with higher automaticity and goal attainment. The message is clear: consistency of context is more important than intensity of effort. Studying for one hour at the same time every day builds habits faster than sporadic four-hour sessions.

How to apply this

Use streaks as your primary habit-building tool. The system counts consecutive study days, giving you a clear number to protect and grow. Visual progress indicators make your consistency tangible, transforming an abstract goal into a concrete achievement. And crucially, allow for planned rest days by pausing streaks – this prevents the perfectionism trap where missing one day leads to complete abandonment.

9. Spacing effect – why distributed learning beats cramming

The phenomenon explained

The Spacing Effect is one of the most robust phenomena in learning psychology: Distributing learning sessions over time is more effective than massed learning ("cramming" before exams).

Why does distributed learning work so much better? The answer lies in how memory actually functions:

- Forgetting enables deeper learning – Counterintuitively, when you've half-forgotten something and then relearn it, the material anchors more deeply in memory

- Context variation strengthens recall – Spreading study across multiple days means you learn in different states and environments

- Sleep consolidates memory – Rest between learning sessions enables the biological process where short-term memories become long-term

Tracking data helps you analyze your learning distribution honestly: Are you studying regularly or only before exams? The calendar view makes this pattern unmistakably clear.

Scientific evidence

The evidence for the spacing effect is overwhelming. Cepeda et al. (2006) published a monumental meta-analysis in the Psychological Bulletin that analyzed 839 assessments of distributed practice across 317 experiments. Their key finding: the optimal interval between learning sessions increased with the retention interval. In practical terms, the longer you want to retain knowledge, the larger the gaps between review sessions should be.

A follow-up study by Cepeda et al. (2008) tested over 1,350 people learning facts with different intervals. They discovered something nuanced: as the gap between learning sessions increased, test performance initially improved and then declined. There exists an optimal interval of about 10–20% of the desired retention period – for example, if you need to remember something for 100 days, your study sessions should be spaced about 10–20 days apart.

The overall pattern is remarkably consistent. Across 271 cases reviewed in the literature, participants with distributed practice outperformed those with massed practice in 259 cases – a success rate of 96%. Cramming simply cannot compete with distributed learning.

How to apply this

Use a calendar view to visualize your learning distribution. At a glance, you can see which days you studied and which you didn't. Patterns become obvious: are you only studying before exams, or maintaining consistent effort throughout the semester? This visual feedback naturally encourages distributed practice. For individual sessions, the Pomodoro Timer optimally structures your time into focused intervals with breaks, preventing the diminishing returns that come from extended cramming sessions.

10. Self-efficacy – belief in your own capability

What is self-efficacy?

Self-efficacy refers to the conviction that one can successfully accomplish a specific task. This term comes from Albert Bandura, one of the most influential psychologists of the 20th century.

People's beliefs about their abilities have a profound effect on those abilities. Ability is not a fixed property; there is huge variability in how you perform.

— Albert Bandura, Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control

Self-efficacy isn't vague self-confidence, but task-specific: You can have high self-efficacy in statistics but low in law. And here's where it gets interesting for tracking:

Documented successes strengthen self-efficacy. When you see that you studied 15 hours last week, you're more likely to believe you can do it again this week. Visible progress builds self-efficacy.

The research base

The research on self-efficacy's importance is striking. Richardson et al. (2012) conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis published in the Psychological Bulletin and found that academic self-efficacy was the strongest single predictor of academic performance among college students – stronger than previous grades, intelligence, or personality. This finding upends conventional wisdom about what predicts academic success.

The mechanism becomes clearer in Zimmerman & Bandura (1994), published in the American Educational Research Journal. They demonstrated that self-regulatory efficacy contributes to academic self-efficacy, which in turn is positively associated with later academic performance. This reveals a virtuous cycle: tracking leads to seeing successes, which builds self-efficacy, which improves performance, which creates more successes to track.

In his landmark book, Bandura (1997) documented that self-efficacious students set higher goals, show more effort and persistence, and consistently outperform peers with lower self-efficacy. The belief in your ability to succeed becomes self-fulfilling.

How to apply this

Build your self-efficacy through visible wins. The Medal Table lets you collect bronze, silver, and gold medals for productive days, turning study time into tangible achievements you can point to. Streaks show how many days you've studied in a row, providing evidence of your consistency. And historical data lets you compare yourself with your past self – the most meaningful comparison you can make. When you see that you studied more this month than last month, you're building the evidence base for believing in your own capability.

11. Attention & time-on-task – the fundamental truth

The simplest principle

Finally, the simplest but most fundamental principle: More active study time correlates with better learning outcomes. It sounds trivial, but is often overlooked.

There's no shortcut: Those who invest more time in high-quality learning learn more. Tracking makes this invested time visible.

The term "time-on-task" describes the time a learner actually spends on a learning task – actively, engaged, focused. Not the time in the library, not the time in front of the book, but the time of real learning.

Tracking makes this distinction possible: The timer only runs when you're actively learning. The coffee break doesn't count. The 20 minutes on Instagram in between doesn't count. You get an honest picture of your net study time.

Scientific evidence

The relationship between time and learning holds up under scrutiny. Jez & Wassmer (2015) found that just 15 more minutes of school per day leads to approximately 1% increase in average overall performance and approximately 1.5% for disadvantaged students. These percentages might seem small, but the effect compounds over years – small daily increments add up significantly, like compound interest for your education.

Godwin et al. (2021) confirmed in Educational Psychology that on-task behavior correlates positively with learning outcomes across different contexts. The relationship between time-on-task and learning is remarkably consistent, whether studying mathematics, languages, or sciences.

The classic foundation comes from Fisher, Marliave & Filby (1979), whose "Beginning Teacher Evaluation Study" established a strong relationship between engaged time and task completion. Decades of subsequent research confirms their core finding: time spent actively learning – not time spent in proximity to books – predicts achievement.

How to apply this

The focus timer is the heart of time-on-task measurement. Fullscreen mode eliminates distractions by hiding everything except your timer, creating a visual commitment to focus. The timer provides honest time measurement – only active study time counts, giving you a truthful picture of your net study time. Pomodoro mode structures focus and break times automatically, preventing the burnout that comes from trying to study without breaks.

For a detailed guide on how to optimally use time tracking, also read Time Tracking as a Student – The Ultimate Guide.

Summary: the science of effective studying

You've now learned 11 scientifically grounded methods to study more effectively:

| # | Concept | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Best Time to Study | 10 AM – 2 PM is peak learning time for most; match study to your chronotype |

| 2 | Metacognition | Tracking promotes reflection on your own learning process |

| 3 | What gets measured | Measurement enables management and optimization |

| 4 | Self-Monitoring | Simply observing improves behavior |

| 5 | Goal-Setting Theory | Specific goals lead to better performance |

| 6 | Feedback Loops | Timely feedback enables adjustment |

| 7 | Self-Determination Theory | Tracking strengthens autonomy and competence experience |

| 8 | Habit Formation | Streaks leverage the mechanisms of habit building |

| 9 | Spacing Effect | Distributed learning dramatically beats cramming |

| 10 | Self-Efficacy | Documented successes strengthen belief in yourself |

| 11 | Time-on-Task | More active study time = more learning success |

Putting science into practice

Athenify was developed to make these 11 principles practically usable without requiring you to think about them constantly. The Dashboard promotes metacognition and provides the feedback loops that research shows are essential for improvement. The Share Price visualizes goal attainment in a way that leverages goal-setting theory. Streaks support habit formation through the "don't break the chain" mechanism. The Medal Table strengthens self-efficacy by documenting your wins. And the Focus Timer maximizes your time-on-task while respecting your brain's need for distributed practice and breaks.

Try Athenify for free

Put all 11 science-backed principles into practice automatically. The research works in the background while you focus on learning.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.