Academic writing is a learned skill, not a talent

Many students believe good writers are simply born that way, but decades of research in composition studies tell a different story. Writing ability is not fixed at birth—it develops through deliberate practice, structured feedback, and repeated revision. Professional authors, researchers, and journalists all produce multiple drafts before publishing. The polished prose you read in textbooks went through rounds of editing that you never see. If the experts rely on revision, why would students expect their first drafts to be perfect?

Writing is thinking made visible. The quality of your writing reflects the quality of your thinking.

The growth mindset, popularized by psychologist Carol Dweck, applies directly to writing. Students who view writing as a process rather than a product improve faster because they embrace feedback instead of fearing it. Every marked-up paper is not a judgment of your intelligence—it is a roadmap for improvement. The difference between a C paper and an A paper often comes down to process: outlining before drafting, revising multiple times, and citing sources correctly. These are habits anyone can develop with the right approach and consistent effort.

The most important shift is treating writing as thinking made visible. When you struggle to explain an idea on paper, the problem is usually that you have not fully understood it yet. The act of writing forces clarity—it exposes gaps in your reasoning, reveals weak evidence, and pushes you to articulate connections you had only vaguely sensed. Students who use a Zettelkasten-style knowledge management system find that connecting ideas across sources makes this process even more powerful. This is why writing deepens understanding more than passive reading ever can, and why the students who write the most learn the most.

The thesis statement: backbone of every paper

A strong thesis statement is the single most important sentence in your entire paper. It tells the reader exactly what you will argue and why it matters. Without a clear thesis, even well-researched papers wander from point to point without arriving anywhere. A good thesis is specific enough to be proven within your page limit, arguable enough that a reasonable person could disagree, and clear enough that a reader knows exactly what to expect from the paragraphs that follow.

Your thesis statement functions as a compass for the entire paper. Every paragraph should connect back to it. If a section does not support or develop your thesis, it does not belong in your paper.

Common thesis mistakes include statements that are too broad ("Technology has changed society"), too obvious ("Exercise is good for health"), or merely descriptive rather than analytical. A strong thesis takes a position and previews the reasoning behind it. Compare "Social media affects teens" with "Social media use exceeding three hours daily correlates with increased anxiety in teenagers because it replaces face-to-face interaction and creates unrealistic social comparisons." The second version gives the paper direction, structure, and an argument worth defending.

Your thesis should function as a compass for the entire paper. Every paragraph should connect back to it, either supporting it with evidence, addressing counterarguments, or extending its implications. If you find a paragraph that does not serve the thesis, either revise the paragraph or revise the thesis. This discipline is what separates focused, high-scoring papers from the rambling essays that professors dread reading. Spend extra time crafting your thesis before you start writing—it saves hours of aimless revision later.

Research and source evaluation

Finding credible sources is the foundation of persuasive academic writing. Not all sources are created equal. Peer-reviewed journal articles, academic books, and reputable institutional reports carry far more weight than blog posts, opinion pieces, or Wikipedia entries. Learning to distinguish primary sources (original research, historical documents) from secondary sources (textbooks, review articles) helps you build stronger arguments and demonstrates scholarly rigor to your professors.

Evaluating source quality requires asking critical questions: Who is the author, and what are their credentials? When was it published, and is the information still current? Where was it published—a peer-reviewed journal or a self-published blog? Does the author present evidence or merely opinion? These evaluation skills transfer beyond academia into every area of life where you need to assess information quality. Building a literature review means reading widely, taking organized notes, and synthesizing multiple perspectives into a coherent narrative that supports your thesis.

Start your research early and cast a wide net before narrowing down. Use your university library databases, Google Scholar, and reference lists from key papers to find relevant sources. As you read, track not just what each source says but how it relates to your argument. A structured approach like the Cornell note-taking method helps you capture key ideas and organize them by theme rather than by author—this makes it much easier to weave them into your paper naturally rather than producing a disjointed list of summaries.

The writing process: from outline to final draft

The most productive writers follow a structured process: outline, draft, revise, polish. An outline is not busy work—it is the architectural blueprint for your paper. A good outline maps your thesis to supporting arguments, assigns evidence to each section, and reveals structural weaknesses before you have invested hours in prose. Students who outline consistently produce more coherent papers and spend less total time writing because they avoid the painful experience of realizing halfway through a draft that their argument does not hold together.

The drafting phase should be separate from editing. When you draft, your goal is to get ideas on paper—not to produce perfect sentences. Write quickly, follow your outline, and resist the urge to go back and fix things. This approach, sometimes called "freewriting," keeps your creative momentum going and prevents the paralysis of perfectionism. You can always fix a bad page; you cannot fix a blank one. Use a study timer to create focused writing blocks of 25 to 50 minutes.

Revision is where good papers become great, and it deserves its own dedicated time. The 30% revision rule suggests allocating nearly a third of your total writing time to revising. Read your draft once for argument structure, once for evidence quality, once for clarity and flow, and once for grammar and formatting. Each pass has a specific purpose. A systematic editing and proofreading process catches logical gaps, tightens prose, and eliminates the errors that distract from your argument.

Build revision time into your study schedule from the start. If your paper is due Friday, aim to finish your first draft by Tuesday so you have three days for revision. This buffer transforms the quality of your work and dramatically reduces stress. The students who consistently earn top marks are not necessarily the most brilliant—they are the ones who give themselves time to revise.

Common academic writing mistakes

The most damaging mistake is submitting a first draft. First drafts are exploratory by nature—they contain redundancies, weak transitions, unsupported claims, and structural problems that only become visible during revision. Yet many students treat the first draft as the final product, either because of poor time management or because they believe revision means simply fixing typos. True revision means rethinking your argument, reorganizing paragraphs, strengthening evidence, and cutting anything that does not serve your thesis.

Submitting your first draft is the single most damaging mistake in academic writing. Every piece of writing improves dramatically with revision. Plan your timeline to include at least two full revision passes before submission.

Other common mistakes include writing without a thesis (or with a thesis so vague it provides no direction), using weak evidence like personal anecdotes where data is needed, and constructing paragraphs without clear topic sentences. Each paragraph should make one point, support it with evidence, and connect it back to your thesis. When paragraphs try to do too much, the writing becomes muddled and the reader loses the thread of your argument.

Citation errors are among the most costly mistakes because they can result in plagiarism charges, even when unintentional. Forgetting to cite a paraphrased idea, misformatting a reference, or failing to include a source in your bibliography all undermine your credibility. Poor proofreading is the final common mistake—spelling errors, grammatical mistakes, and formatting inconsistencies signal carelessness and distract professors from your argument. These errors are entirely preventable with a structured writing process that includes dedicated revision time.

Citations and plagiarism: getting it right

Citations are not just formalities—they are trust signals. Professors use citations to evaluate whether you have engaged seriously with the literature. Incorrect or missing citations do not just cost you marks; they can trigger plagiarism flags that carry serious academic consequences. The three major citation styles each serve different disciplines: APA (American Psychological Association) is standard in social sciences, psychology, and education; MLA (Modern Language Association) is used in humanities and literature; Chicago/Turabian is common in history, arts, and some business courses.

Citation errors are among the most costly and easily avoidable mistakes in academic writing. A missing citation can be interpreted as plagiarism, regardless of intent. Always cite as you write, not after.

Learning proper citation formats early in your academic career pays dividends on every paper you write. Each style has specific rules for in-text citations, reference lists, and formatting details like italics and punctuation. Rather than memorizing every rule, learn the general logic of your primary style and use a reference manager to handle the details. Tools like Zotero, Mendeley, and EndNote can automatically format your citations and bibliography, saving hours of tedious manual work. Pairing a reference manager with a digital second brain for students creates a research system where every source, note, and idea is organized and retrievable when you need it.

Plagiarism anxiety is real—and avoidable. One in three students report worrying about unintentional plagiarism. The solution is straightforward: take careful notes during research, always track which ideas came from which sources, and learn to paraphrase properly. Proper paraphrasing means understanding an idea fully and expressing it in your own words and sentence structure—not just swapping synonyms. When in doubt, cite it. Understanding how to avoid plagiarism removes the anxiety and lets you write with confidence.

How Athenify supports your writing process

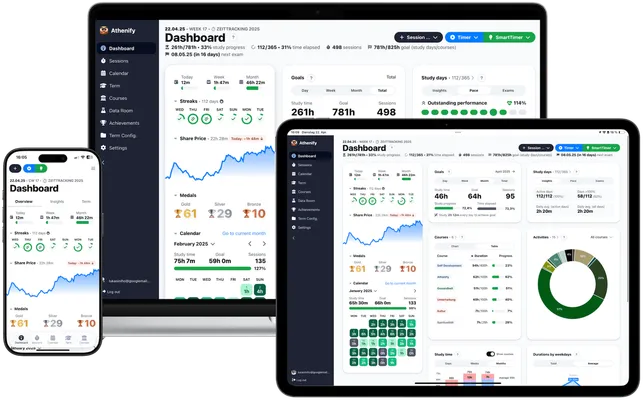

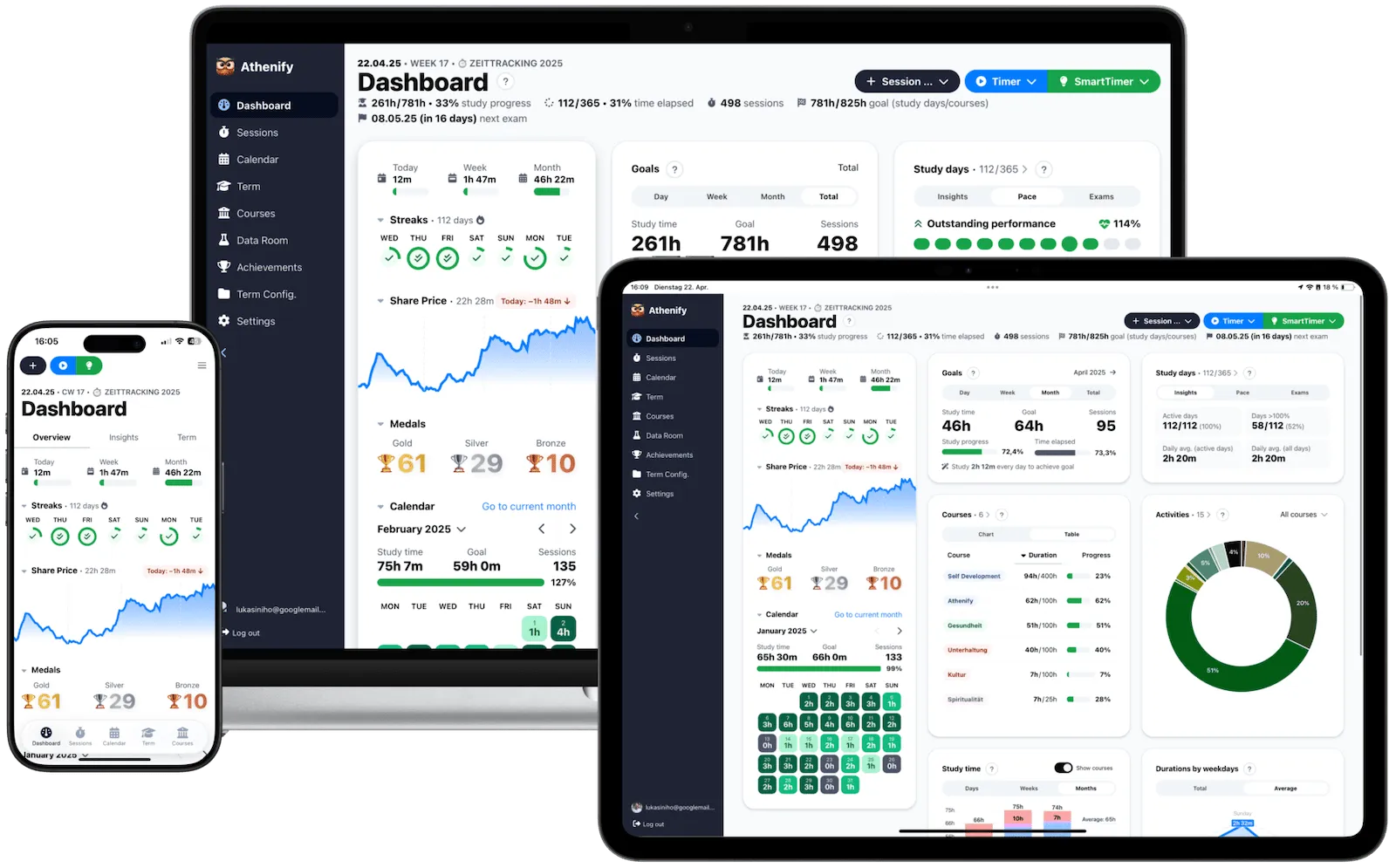

Writing a research paper is not a single task—it is a series of distinct phases that each benefit from focused attention. Athenify's Pomodoro timer lets you dedicate structured blocks to research, outlining, drafting, revising, and formatting. By breaking the writing process into timed sessions, you prevent the overwhelm that leads to procrastination and make steady progress instead of staring at a blank page for hours.

Athenify's time tracking shows you exactly how long each writing phase takes, helping you plan future assignments more accurately. The streak feature builds a daily writing habit—because consistent practice is what transforms writing from a dreaded chore into a natural skill. Session planning lets you map out your writing week in advance, ensuring you allocate enough time for revision instead of rushing to submit a first draft at the last minute.

Your writing improvement action plan

Start today with one simple change: outline before you write. Before your next assignment, spend 20 minutes creating a structured outline with your thesis, main arguments, and supporting evidence mapped to each section. This single habit will improve your paper's coherence more than any other change. Then commit to writing daily, even if only for 15 minutes—summaries of readings, reflections on lectures, or freewriting about your thesis topic all build fluency.

Revise systematically by making multiple passes with different purposes: structure, evidence, clarity, grammar. Seek feedback from your university writing center, professors' office hours, or trusted peers—external perspectives reveal blind spots you cannot see on your own. Finally, track your writing practice with Athenify to build the consistency that transforms writing from an anxiety-inducing assignment into a skill you are genuinely confident in. Apply the same deliberate practice techniques that work for any complex skill, and watch your writing improve paper by paper.

Try Athenify for free

Plan your writing projects with Athenify

No credit card required.

No credit card required.