Most students take notes the same way they did in middle school: write down everything the professor says, hope for the best, and re-read it all the night before the exam. It feels productive in the moment. It rarely produces results.

The Cornell Note-Taking Method offers something fundamentally different--not just a way to capture information, but a system that forces you to process and review it. Developed over 70 years ago, it remains one of the most research-backed note-taking methods available to students. And yet most people who have heard of it have never actually used it properly.

This guide covers everything: the exact setup, how to take notes during lecture, how to write effective cue questions, how to review, and when Cornell notes are--and aren't--the right choice.

The Cornell Method doesn't just organize your notes. It builds a review system directly into the note-taking process.

The origin of Cornell notes

Professor Walter Pauk developed the Cornell Note-Taking System in the 1950s at Cornell University. He wasn't trying to invent something clever--he was trying to solve a real problem. His students were taking extensive notes in class but struggling to use them effectively when studying for exams.

Pauk's insight was deceptively simple: the problem wasn't how students captured information. It was that their notes offered no pathway back into the material. A page full of dense paragraphs gives you nothing to grab onto during review. You end up re-reading passively, which research consistently shows is one of the least effective study strategies.

His solution was structural. By dividing the page into distinct zones with distinct purposes, he created a system where review is built into the format itself.

How to set up a Cornell note page

The setup takes about 30 seconds and should be done before class begins. You need three sections on every page.

The three zones

1. The notes column (right side, approximately 6 inches wide) This is your main workspace during class. Lecture content, examples, diagrams, and key details go here. Think of it as a slightly more organized version of whatever you're already doing--but confined to the right two-thirds of the page.

2. The cue column (left side, approximately 2.5 inches wide) Leave this completely blank during class. This is the critical piece most people skip. After class, you'll fill it with questions, keywords, and prompts that correspond to your notes on the right. The cue column transforms your notes from a passive record into an active study tool.

3. The summary section (bottom, approximately 2 inches tall) After reviewing your notes and filling in the cue column, write a 2-3 sentence summary of the entire page. This forces you to distill the lecture down to its essential message.

Drawing the lines

For physical notebooks:

- Place your ruler 2.5 inches (about 6.5 cm) from the left edge

- Draw a vertical line from top to bottom

- Draw a horizontal line about 2 inches (5 cm) from the bottom

- Label the date and topic at the very top of the page

For digital setups, most note-taking apps (Notion, OneNote, GoodNotes) offer Cornell templates. Use them--don't try to recreate the layout with tables every time.

Phase 1: Taking notes during lecture

During class, your only job is to write in the notes column. Don't touch the cue column. Don't worry about the summary. Focus entirely on capturing the lecture content.

What to write down

Not everything. This is the most common mistake with any note-taking method, and it's worth repeating: your goal is to capture main ideas, not to transcribe. Specifically, focus on:

- Main concepts and definitions -- the ideas the professor emphasizes, repeats, or writes on the board

- Examples and illustrations -- concrete instances that clarify abstract ideas

- Formulas, dates, and specific facts -- anything precise that you can't reconstruct from memory

- Connections -- moments when the professor links the current topic to previous material

- Your own confusion -- mark anything you don't understand with a question mark

What to skip

Don't write down anything you can easily find in the textbook or slides. Don't transcribe anecdotes the professor uses for entertainment. Don't copy down examples verbatim if you understand the principle--write the principle instead and add a brief note about the example.

Formatting tips for the notes column

Use abbreviations consistently. Develop your own shorthand: "w/" for "with," "bc" for "because," "def" for "definition," "ex" for "example," and so on. Leave space between topics--you'll want room to add details later. Use bullet points or dashes rather than full sentences. Underline or star key points as the professor emphasizes them.

The notes column is for capturing. The cue column is for thinking. Don't mix them up.

Phase 2: Creating the cue column

This is where the Cornell Method earns its reputation. Within 24 hours of the lecture--ideally the same evening--sit down with your notes and fill in the cue column. This step typically takes 10-15 minutes per page and serves as your first genuine review.

How to write effective cues

For each section of your notes, generate one or more of the following in the cue column:

Questions that test understanding: If your notes say "Photosynthesis occurs in the chloroplast, using light energy to convert CO2 and water into glucose and oxygen," your cue might be: "Where does photosynthesis occur and what does it produce?"

Keywords that trigger recall: For a section on the causes of World War I, your cues might be: "Alliance system," "Assassination," "Imperialism," "Militarism."

Conceptual prompts: "How does X relate to Y?" or "Why is Z important?" These force you to think about relationships rather than just facts.

Comparison prompts: "Difference between mitosis and meiosis?" These work well when the lecture covers contrasting concepts.

The cue column as a diagnostic tool

Pay attention to sections where you struggle to write cues. If you can't formulate a question about your notes, it usually means one of two things: either the material was trivial and doesn't need a cue, or you didn't understand it well enough to question it. The second case is a signal to revisit the textbook or ask the professor.

Phase 3: Writing the summary

After completing your cues, write a 2-3 sentence summary at the bottom of the page. This is the hardest part for most students--not because it's complex, but because it requires synthesis.

What makes a good summary

A good summary answers: "If I could only remember one thing from this page, what would it be?" It captures the core argument, principle, or takeaway--not a list of everything covered.

Weak summary: "This lecture covered photosynthesis, cellular respiration, and ATP production."

Strong summary: "Photosynthesis and cellular respiration are complementary processes: photosynthesis stores energy from sunlight in glucose, and cellular respiration releases that energy as ATP for cellular work."

The weak version lists topics. The strong version captures the relationship between them--which is what you'll actually need to understand for exams.

Phase 4: Reviewing with Cornell notes

The entire point of the Cornell structure is to make review active rather than passive. Here's the protocol.

The cover-and-recall method

- Fold the page or cover the notes column with a blank sheet

- Read the first cue in the left column

- Try to recall the corresponding information from memory--say it aloud or write it on a separate page

- Uncover the notes column and check your answer

- Mark cues you answered incorrectly or incompletely

- Move to the next cue and repeat

This is active recall in its purest form--the same principle that makes flashcards effective, but built directly into your notes.

The spaced review schedule

Don't cram all your review into one session. Space it out following the forgetting curve:

- Day 1 (within 24 hours): Create cues and summary. Do your first cover-and-recall pass. This is the most critical review session.

- Day 3: Quick review. Cover the notes column and test yourself on all cues. Focus extra time on any you missed.

- Day 7: Full review. By now, most material should feel solid. Flag persistent problem areas.

- Day 14: Final review before the material enters long-term memory. At this point, you should be able to answer most cues without hesitation.

This schedule aligns with spaced repetition research--intervening at the moments when memories are about to fade, reinforcing them at optimal intervals.

When Cornell notes work best

The Cornell Method isn't universally optimal. It excels in specific contexts and struggles in others.

Ideal use cases

Lecture-heavy humanities courses: History, psychology, political science, sociology--anywhere you're receiving dense verbal information that requires later recall. The cue column is perfectly suited for the "who, what, when, why" questions that dominate these fields.

Courses with cumulative exams: When you need to retain material over an entire semester, the built-in review system pays enormous dividends. Students who use Cornell consistently report needing less cramming before finals.

Courses where the professor lectures linearly: If the lecture follows a logical sequence (topic A leads to topic B leads to topic C), the notes column captures this flow naturally.

When to choose a different method

Highly visual or diagrammatic subjects: If the lecture involves complex diagrams, molecular structures, or mathematical proofs, the two-column structure can feel constraining. Consider mind mapping for visual content.

Discussion-based seminars: When ideas emerge non-linearly from group discussion, the Cornell structure can feel forced. Flow-based notes may capture the organic development of ideas more naturally.

Fast-paced technical lectures: If the professor moves through material so quickly that you can barely keep up, the outline method may be faster. Cornell requires some breathing room to organize notes in the right column.

Adapting Cornell for different subjects

Cornell for STEM

Use the notes column for worked examples, step-by-step derivations, and diagram explanations. In the cue column, write the problem type or theorem name. Your cues become a catalog of problem types: "How to solve a second-order differential equation," "When to apply L'Hopital's rule."

The summary section becomes a formula reference: write the key equation or theorem from the page along with the conditions for its application.

Cornell for languages

Use the notes column for grammar explanations, example sentences, and usage patterns. The cue column becomes a mini-quiz: write the English meaning (or a prompt) on the left, the target-language construction on the right. This turns every page into a study card for grammar concepts.

Cornell for law

Law students find Cornell particularly effective for case briefs. The notes column holds the case facts, reasoning, and ruling. The cue column contains the legal principle, the rule of law, and comparison prompts ("How does this differ from previous case?"). The summary captures the holding in one sentence.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Mistake 1: Treating it like regular notes

The most common failure mode is taking notes in the right column and never touching the cue column or summary. At that point, you're just taking notes on a page with lines drawn on it. The method's power lives entirely in phases 2-4. If you skip them, you're not using Cornell--you're using a two-column layout.

Mistake 2: Writing cues during lecture

The cue column should be blank during class. If you try to generate questions while simultaneously capturing lecture content, you'll do both poorly. Separate capture from processing.

Mistake 3: Making cues too easy

"What year did WWI start?" is not a useful cue if the answer is a single date you can look up in two seconds. Better: "What combination of factors made 1914 the tipping point for European conflict?" Cues should require genuine recall and understanding.

Mistake 4: Never reviewing

Cornell notes without review are just notes with lines drawn on them.

The review phase is not optional. If you consistently skip the cover-and-recall step, switch to a simpler method like outlining. The Cornell Method's advantage is its review system--without it, you're adding setup complexity for no benefit.

Mistake 5: Using Cornell for everything

No single method works for every subject. If you're struggling with Cornell in a particular class, that's a signal to try a different approach, not to push harder. Effective students use 2-3 methods across their courses, matching each one to the subject's demands. See our complete guide to note-taking methods for alternatives.

Building Cornell into your daily routine

The Cornell Method requires discipline, but less than you might think. Here's a realistic daily workflow.

Before class (30 seconds)

Draw your lines. Write the date and topic. Open to a fresh page.

During class (the full lecture)

Take notes in the right column. Focus on main ideas. Use abbreviations. Leave space between topics.

After class, same day (10-15 minutes)

Review notes. Fill in cue column with questions and keywords. Write the summary. Flag anything you don't understand.

Review sessions (5-10 minutes per session)

Follow the spaced schedule: days 1, 3, 7, 14. Cover notes, answer cues, check accuracy.

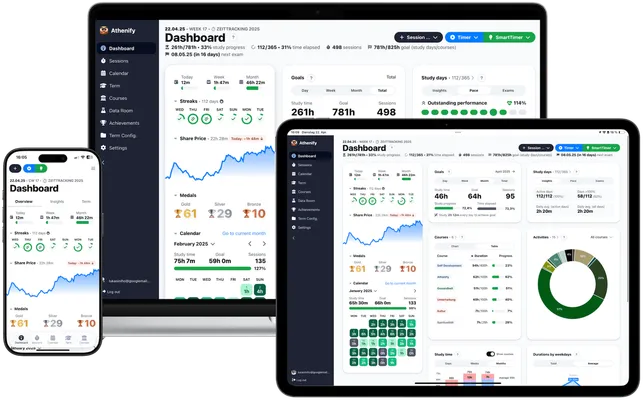

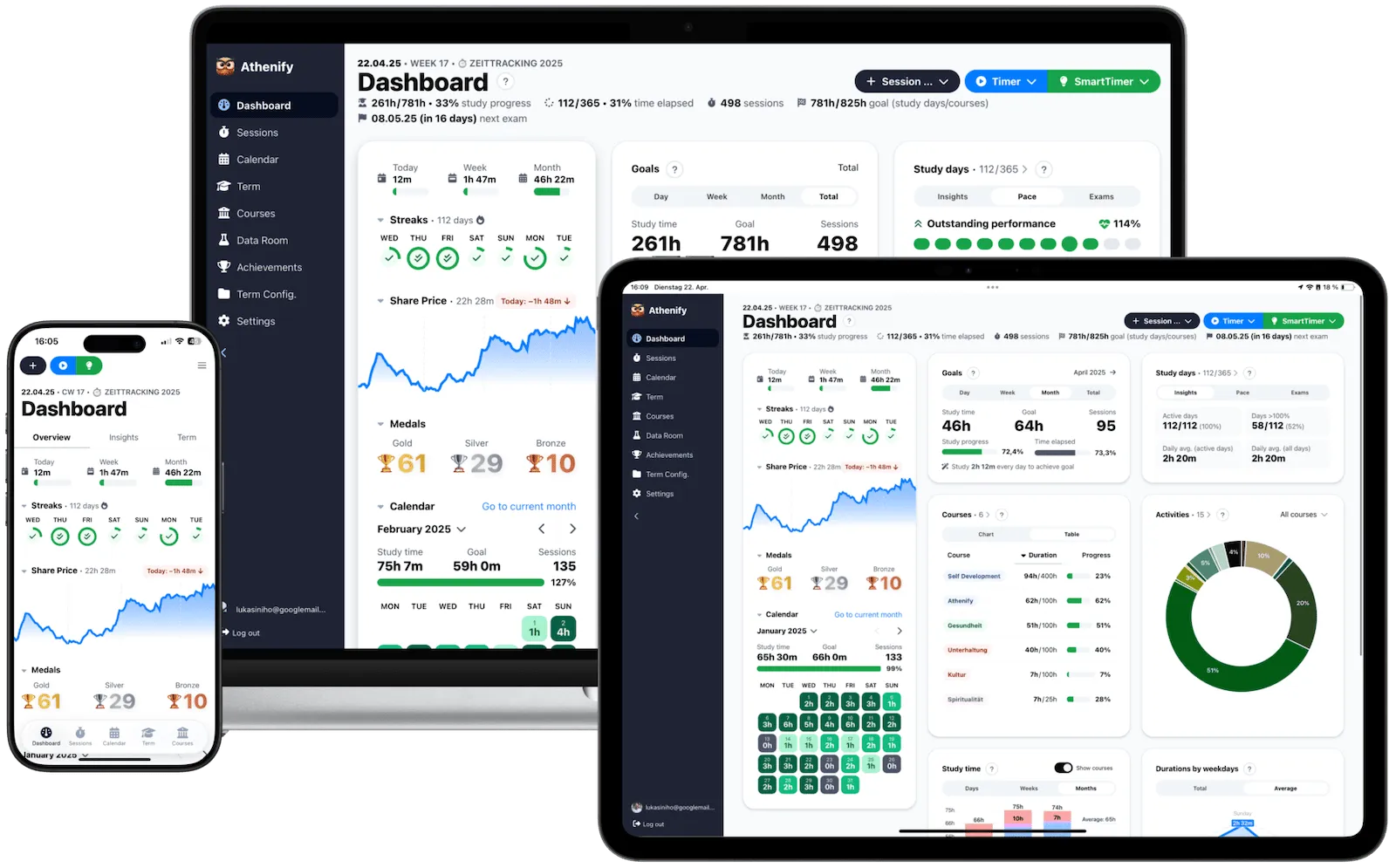

The total extra time investment is roughly 15-20 minutes per lecture--a fraction of the cramming time it saves before exams. Track your review sessions alongside your study habits to ensure consistency. If you find your focus wavering during review, try structuring sessions with the Pomodoro Technique or applying strategies from our guide on how to focus when studying.

Try Athenify for free

Track your Cornell note review sessions and build consistent study streaks. See exactly how much time you're investing in each subject--and where you need more.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Conclusion

The Cornell Note-Taking Method has survived seven decades not because it's trendy, but because it works. Its three-zone structure solves the fundamental problem of student notes: they're written once and never properly reviewed.

The cue column transforms passive notes into an active recall tool. The summary forces synthesis. The review protocol spaces practice at optimal intervals. Together, these elements create a complete learning system--not just a way to write things down.

Start with one class. Set up the page before lecture. Take notes in the right column. Fill in cues that evening. Write your summary. Then cover the notes and test yourself. Do this consistently for two weeks, and you'll understand why a method from the 1950s still outperforms everything that's come after it.