You have experienced it before, even if you did not have a name for it. You sat down to study, started working through a problem set, and suddenly two hours had vanished. Not because you were procrastinating--the opposite. You were so deeply absorbed in the work that time, self-consciousness, and the outside world all faded away. You were not fighting to concentrate. Concentration was simply happening.

That was flow.

Most students treat flow as a happy accident--something that occasionally happens on a good day. But Csikszentmihalyi's research, and decades of neuroscience that followed, reveals something far more useful: flow is not random. It emerges when specific conditions are met. And once you understand those conditions, you can create them deliberately.

Flow is not a personality trait or a lucky break. It is a predictable neurological state that arises when the right conditions are present.

The neuroscience of flow

Understanding what happens in your brain during flow explains why it feels the way it does--and why it is so productive.

Transient hypofrontality

During flow, your prefrontal cortex--the brain region responsible for self-monitoring, time perception, and critical inner dialogue--partially deactivates. This phenomenon, called transient hypofrontality, is what produces the signature characteristics of flow:

- Time distortion: Hours feel like minutes because the brain region that tracks time is quieter

- Reduced self-consciousness: Your inner critic goes silent because the self-monitoring circuits dial down

- Effortless concentration: Focus feels natural because the brain resources normally spent on distraction and self-doubt are redirected to the task

- Enhanced pattern recognition: With the analytical prefrontal cortex taking a back seat, deeper brain structures that handle intuition and pattern-matching get more bandwidth

Neurochemical cocktail

Flow triggers a specific cocktail of neurochemicals that enhance performance:

- Dopamine: Increases focus, pattern recognition, and the sense of reward

- Norepinephrine: Heightens attention and arousal

- Endorphins: Reduce pain perception and create a mild euphoria

- Anandamide: Enhances lateral thinking and the ability to make novel connections

- Serotonin: Produces the calm, satisfied feeling that accompanies flow

This combination explains why flow does not just feel productive--it feels good. Your brain is literally rewarding you for being deeply engaged with a challenging task.

The four conditions for flow

Csikszentmihalyi identified specific conditions that reliably trigger flow. For studying, these translate into four practical requirements.

1. Challenge-skill balance

This is the most critical condition. Flow occurs when the difficulty of your task sits in a narrow band: challenging enough to fully engage your cognitive resources, but not so difficult that it produces anxiety.

| Task difficulty vs. skill level | Mental state |

|---|---|

| Far below skill level | Boredom, mind-wandering |

| Slightly below skill level | Relaxation, easy focus |

| Matched to skill level | Flow zone |

| Slightly above skill level | Stretch, high engagement |

| Far above skill level | Anxiety, frustration, avoidance |

The flow zone typically sits at about 4 percent beyond your current ability--enough to stretch you without overwhelming you. This is why studying material that is too easy (rereading notes you already know) and material that is too hard (tackling advanced problems without prerequisites) both fail to produce flow. You need to be working at your edge.

2. Clear goals

Flow requires a clear sense of what you are trying to accomplish. Vague intentions like "study biology" do not trigger flow. Specific goals like "work through practice problems 1 through 10 on cellular respiration without looking at solutions" do.

Clear goals work because they:

- Give your brain a concrete target to lock onto

- Provide immediate feedback (you either solved the problem or you did not)

- Eliminate the decision fatigue of figuring out what to do next

Before each study session, write down one to three specific goals. Not subjects. Not topics. Concrete, completable tasks.

3. Immediate feedback

Flow requires a continuous loop of action and feedback. You try something, see the result, and adjust. This is why activities like playing music, rock climbing, and gaming produce flow so reliably--the feedback is instant.

For studying, you can create faster feedback loops through:

- Active recall: Test yourself, then check answers immediately. Each question gives you instant feedback on your understanding

- Practice problems: Attempt a problem, then check the solution. The gap between your answer and the correct one tells you exactly where you stand

- Teaching aloud: Explain a concept as if teaching someone else. Stumbling reveals gaps in real time

- Writing: Each sentence you write gives feedback about whether you truly understand the material

Passive studying methods like highlighting and rereading provide almost no feedback, which is one reason they rarely produce flow. For more on active engagement techniques, see our guide on how to focus when studying.

4. Uninterrupted time

Flow takes 10 to 25 minutes of continuous focus to develop. A single interruption--a phone notification, a roommate's question, a browser tab switch--resets the clock. This means you need a minimum of 90 uninterrupted minutes to enter flow and sustain it long enough to be productive.

A single notification can cost you 25 minutes of flow. That is not hyperbole--it is the measured time to re-enter deep concentration after an interruption.

This is the condition students most frequently violate. You might have the perfect challenge level, clear goals, and immediate feedback--but if your phone buzzes every 10 minutes, flow will never arrive.

A practical flow protocol for studying

Here is a step-by-step protocol for creating flow conditions before and during your study sessions.

Before the session (5 minutes)

- Choose one task. Not a subject--a specific, completable task. "Complete 15 organic chemistry reaction mechanism problems" beats "study chemistry"

- Assess the challenge level. Is this material slightly above your current comfort zone? If not, adjust the difficulty up or down

- Prepare your environment. Phone in another room. One browser tab open. Desk cleared of everything unrelated. For detailed environment design, see our guide on study environment optimization

- Set a timer for 90 minutes. Use a dedicated study timer that will not send you notifications. Do not plan to check anything until the timer ends

- Take three deep breaths. This sounds trivial but it activates your parasympathetic nervous system and creates a psychological transition point between "pre-study mode" and "study mode"

During the session

- Start working immediately. Do not ease into it. Dive into your first problem or question. The faster you engage, the faster flow arrives

- Resist the urge to check anything. The first 15 minutes are the hardest. Your brain will generate urges to check your phone, email, or social media. Note the urge, let it pass. It will dissipate within 30 to 60 seconds

- Use a capture list. Keep a notepad nearby. When unrelated thoughts intrude ("I need to respond to that email"), write them down and immediately return to your task. This tells your brain the thought will not be lost

- Do not switch tasks. If you finish one problem set, move to the next related task. Task-switching breaks flow

- Ignore the clock. Once you are working, do not check the timer. Flow involves losing track of time. Let it happen

After the session

- Log your session. Record how long you studied, what you accomplished, and how the session felt. Over time, this data reveals your personal flow patterns

- Take a genuine break. Walk, stretch, hydrate. Do not check your phone for at least 5 minutes after the session ends--give your brain time to transition out of flow gradually

Matching study techniques to flow

Not all study methods are equally compatible with flow. Here is how common techniques rank:

High flow potential

Practice problems and problem sets: The challenge-feedback loop is tight and continuous. Each problem is a mini-cycle of effort, feedback, and adjustment--exactly what flow requires.

Essay writing and extended composition: Once you have an outline and start writing, the continuous act of translating thoughts into words creates a natural flow rhythm. Many writers describe their best work emerging during flow states.

Active recall with self-testing: Testing yourself on material, then checking answers, provides immediate feedback and requires genuine cognitive effort--both flow triggers.

Coding and programming: The challenge-feedback loop is extremely tight. Write code, run it, see the result, fix errors, repeat. Programming is one of the most flow-compatible activities that exists.

Low flow potential

Passive rereading: No feedback loop, no challenge. Your brain disengages quickly.

Highlighting text: Feels productive but requires minimal cognitive effort. Falls well below the challenge threshold for flow.

Copying notes: Mechanical transcription does not engage deep processing. Your mind wanders while your hand moves.

Watching video lectures passively: Unless you are actively pausing to take notes and test yourself, video lectures rarely produce flow because they put you in a receptive rather than active mode.

The pattern is clear: flow favors active, challenging engagement over passive absorption. If your study method does not require you to generate responses, solve problems, or create something, it is unlikely to produce flow.

Common flow blockers (and how to remove them)

Perfectionism

Perfectionism kills flow because it amplifies the self-monitoring that flow suppresses. If you are constantly evaluating whether your work is good enough, you are engaging the prefrontal cortex that needs to quiet down for flow to occur.

The fix: give yourself permission to produce imperfect work during your flow session. You can edit, revise, and improve later. The first pass is about maintaining momentum and staying in the zone.

Multitasking

Multitasking is the opposite of flow. Flow requires single-pointed attention on one task. Switching between your essay, a research paper, and a text message does not just break flow--it prevents it from ever developing.

The fix: commit to one task per session. If you have multiple subjects to cover, schedule separate blocks for each with breaks in between. Our guide on deep work covers this in detail.

Anxiety about results

Worrying about your grade, your GPA, or your future while studying pulls you out of the present moment and into your prefrontal cortex--exactly the brain region that needs to quiet down for flow. The paradox is that flow produces better results, but you cannot enter flow while worrying about results.

The fix: focus on the process, not the outcome. Your goal for this session is not "get an A." It is "complete these 15 problems." Trust that consistently entering flow will produce the outcomes you want.

Physical discomfort

Hunger, thirst, uncomfortable temperature, a bad chair, or needing to use the bathroom will all prevent flow. Your brain cannot ignore physical distress, no matter how interesting the material.

The fix: address all physical needs before you start. Eat a meal. Fill a water bottle. Adjust the temperature. Use a chair that supports good posture. These are not luxuries--they are prerequisites.

You cannot think your way into flow. You have to remove everything that blocks it and let it arrive.

Tracking your flow sessions

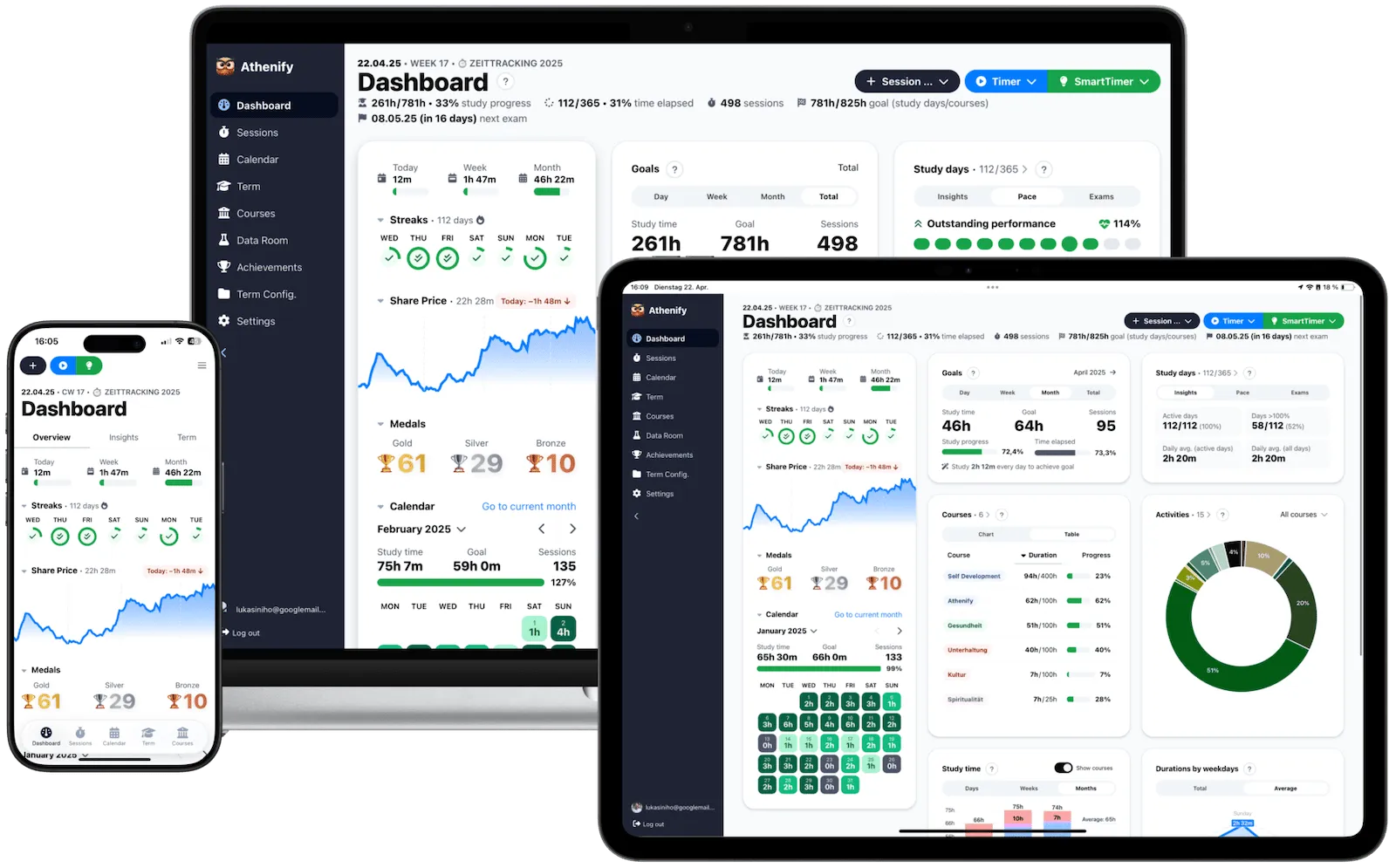

One of the most useful habits you can build is tracking when flow occurs and what conditions preceded it. Over time, you will discover your personal flow profile--the specific combination of time, location, task type, and preparation that most reliably triggers immersion.

After each study session, note:

- Did flow occur? (Yes / Partially / No)

- How long did it take to enter flow? (Minutes)

- What time of day was it?

- Where were you studying?

- What were you working on?

- Was your phone present?

- How difficult was the material relative to your skill level?

After two to three weeks of this data, patterns will emerge. Maybe you enter flow most easily at 9 AM in the library working on math problems. Maybe afternoon reading sessions never produce flow, but morning ones do. These insights let you schedule your most important studying during your peak flow windows.

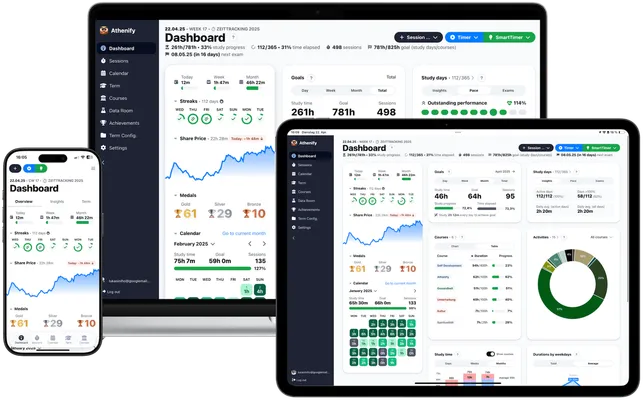

Try Athenify for free

Track your study sessions and identify your flow patterns. Athenify helps you see exactly when and where you do your deepest work.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Flow and the bigger picture

Flow is not just a productivity hack. Csikszentmihalyi's research found that people who experience regular flow states report higher life satisfaction, greater sense of meaning, and lower anxiety. When you are in flow, you are not just studying effectively--you are experiencing one of the most psychologically rewarding states available to humans.

This reframes studying entirely. Instead of being something you endure to get a grade, studying becomes a practice that can produce genuine fulfillment--when you approach it with the right conditions.

The path to consistent flow is straightforward, even if it is not always easy: remove distractions ruthlessly, set clear and specific goals, choose tasks that stretch your abilities without overwhelming them, and protect 90-minute blocks of uninterrupted focus time. Do this consistently and flow will shift from a rare accident to a regular part of your academic life.

The students who master flow do not just get better grades. They discover that learning itself can be deeply enjoyable--and that discovery changes everything.