You are sitting in a lecture hall. Half the students have laptops open, fingers flying across keyboards. The other half are scribbling in notebooks, pens barely keeping up. Both groups believe they are doing the right thing. Both groups can cite studies supporting their choice. And both groups are partly wrong.

The digital-vs.-handwritten debate has been raging since laptops became common in classrooms, and it has generated more heat than light. Proponents of handwriting point to studies showing better retention. Digital advocates counter with evidence on organization and long-term access. The truth, as usual, is more interesting than either side's talking points.

This guide examines what the research actually says--not the headlines, but the methodology, the effect sizes, and the conditions under which each approach excels. The answer is not "handwriting wins" or "digital wins." The answer is that different situations demand different tools, and the students who perform best are the ones who know when to use each.

The question isn't whether to use a pen or a laptop. It's whether you're processing information or just recording it.

The landmark study: Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014)

The study that launched a thousand "put away your laptop" articles was published by Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer in Psychological Science. It is the most cited paper in the handwriting-vs.-typing debate, and it is worth understanding in detail--both for what it found and what it didn't.

What they did

Across three experiments, college students watched TED talks and took notes either by hand or on a laptop. They were then tested on the material--both factually (recall of specific details) and conceptually (applying and integrating ideas).

What they found

Laptop users recorded significantly more words. But on conceptual questions, handwriters performed better. Critically, Mueller and Oppenheimer found that the more verbatim the laptop notes, the worse the conceptual performance. Transcription was the culprit, not the device itself.

In their third experiment, they warned laptop users: "Don't transcribe. Put things in your own words." It didn't help. The laptop users still transcribed more and still performed worse on conceptual questions. The temptation to capture everything verbatim, it seems, is nearly irresistible when your typing speed allows it.

What the study didn't test

The study tested recall after a single viewing with no opportunity for review. This is a significant limitation. In real academic life, you don't just take notes and then take a test. You review, revise, reorganize, and build on your notes over weeks. The study tells us about initial encoding--it tells us nothing about the full learning cycle.

The replication attempts

Science doesn't rest on single studies. Since 2014, several research groups have attempted to replicate Mueller and Oppenheimer's findings.

Morehead et al. (2019)

A large-scale replication study by Morehead, Dunlosky, and Rawson found no significant difference between handwritten and typed notes on either factual or conceptual questions. They did replicate the finding that laptop users wrote more words and used more verbatim overlap--but this didn't translate into worse performance.

Urry et al. (2021)

A multi-lab replication coordinated across eight universities, involving over 1,100 students, also failed to find a significant advantage for handwritten notes. The researchers concluded that the original effect, if it exists, is smaller than initially reported.

The emerging consensus

The current state of the evidence looks something like this: handwriting produces a small encoding advantage for conceptual material, likely because it forces slower, more selective processing. But this advantage can be reduced or eliminated when laptop users are trained to take selective notes, and it may be outweighed by digital advantages when notes are reviewed and used over time.

The real variable: processing depth

Here is what both sides of the debate often miss: the medium is less important than the method. A student taking thoughtful, selective typed notes will outperform a student mindlessly copying a professor's words by hand. And a student who handwrites detailed, well-organized notes will outperform a student typing a stream-of-consciousness transcript.

Handwriting doesn't magically create understanding. It creates a constraint that forces processing. If you can process without the constraint, the medium doesn't matter.

The variable that actually predicts learning outcomes is processing depth--how much you think about the material as you write it. Handwriting enforces this naturally through speed limitations. Typing allows it but doesn't enforce it. The question you should ask is not "pen or laptop?" but "Am I processing or transcribing?"

Signs you are transcribing (regardless of medium)

- You are writing in complete sentences that match the professor's words

- You can't summarize what you just wrote without re-reading it

- Your notes are long but you feel like you haven't learned anything

- You could have been replaced by an audio recorder

Signs you are processing

- You are paraphrasing in your own words

- You are selecting what to write and leaving things out

- You are making connections to previous material

- You could explain what you just wrote to a classmate

When handwriting wins

Despite the nuances in the research, there are clear situations where handwriting has real advantages.

First-time conceptual learning

When you encounter material for the first time and need to build understanding--not just record facts--handwriting forces the processing that builds comprehension. This applies to philosophy, theoretical physics, literary analysis, and any subject where understanding relationships matters more than memorizing details.

Distraction-prone environments

The research on laptop distraction is far less controversial than the encoding debate. Studies consistently show that students on laptops are distracted by non-academic content (email, social media, messaging) for significant portions of class time. And the distraction isn't limited to the laptop user--students sitting behind an open laptop also perform worse.

Diagram-heavy subjects

For subjects involving diagrams, chemical structures, mathematical notation, or spatial relationships, handwriting (or a tablet stylus) is simply faster and more natural. Try drawing an organic chemistry mechanism with a keyboard. Exactly.

When the professor bans laptops

An increasing number of professors are restricting devices in classrooms, citing distraction research. In these cases, having strong handwriting habits isn't optional--it's required. Understanding effective note-taking methods for pen and paper, such as the Cornell Method, becomes essential.

When digital wins

Digital note-taking has advantages that handwriting cannot match, particularly for activities beyond the lecture itself.

Long-term knowledge management

If you are building a knowledge system that spans semesters--a second brain or a Zettelkasten--digital tools are essential. You cannot hyperlink paper notes. You cannot search a handwritten notebook for every mention of "neuroplasticity." Digital notes enable the kind of networked, searchable, evolving knowledge base that becomes more valuable over time.

Speed-dependent courses

Some courses demand speed. A fast-talking professor covering dense technical material, a law lecture reviewing multiple cases, a computer science class with code examples--in these contexts, handwriting simply cannot keep up. Typed notes, even if slightly less processed, capture information that would otherwise be lost entirely.

Collaboration and sharing

Digital notes can be shared instantly, co-edited in real time, and integrated with group study systems. For study groups preparing for exams, digital notes are dramatically more efficient than photographing handwritten pages.

Organization and retrieval

Tags, folders, search, links, backlinks--digital tools offer organization capabilities that paper fundamentally cannot match. As your note collection grows across semesters, the ability to find and connect information becomes increasingly valuable.

The hybrid approach: best of both worlds

Given the evidence, the most effective strategy for most students is not choosing one medium but using both strategically. This is the approach recommended by learning scientists and adopted by high-performing students across disciplines.

The workflow

During lecture: handwrite. Take notes by hand using a structured method like the Cornell Method or mind mapping. Focus on capturing main ideas, connections, and your own thoughts. Let the physical constraint of handwriting force you to process rather than transcribe.

Within 24 hours: digitize selectively. Don't type up everything you wrote. Extract the key ideas, important details, and connections worth preserving. This selective digitization serves as your first review session--you are revisiting the material, deciding what matters, and restating it in a permanent format.

For long-term storage: link and organize. Place your digitized notes into your knowledge management system. Link related concepts across courses. Add them to structure notes or mind maps that show the bigger picture. This is where digital tools earn their keep.

For tablet users

Tablets with styluses (iPad + Apple Pencil, reMarkable, Samsung Galaxy Tab) offer an intriguing middle path. You get the encoding benefits of handwriting with the organizational benefits of digital storage. Apps like GoodNotes, Notability, and Apple Notes allow handwritten notes that are searchable via handwriting recognition.

The main caveat: tablets carry distraction risk. If your iPad also has Instagram, Twitter, and email, the temptation will be present. Consider using Focus modes or dedicated apps during lectures to minimize this.

Matching medium to method

Different note-taking methods pair differently with handwriting and digital tools.

| Method | Handwriting | Digital | Best medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cornell | Natural fit; draw lines, write cues | Templates available; easy review | Either; handwrite for lectures, digitize for review |

| Mind mapping | More creative; free-form drawing | Unlimited space; easy reorganization | Handwrite first, digitize complex maps |

| Outlining | Slower but forces selectivity | Fast; easy to reorganize levels | Digital for speed-dependent lectures |

| Zettelkasten | Luhmann's original was handwritten | Bidirectional links transform the system | Digital strongly preferred |

| Flow-based | Natural for diagrams and connections | Limited by linear typing | Handwrite or tablet |

What about recording lectures?

Some students bypass the debate entirely by recording lectures and reviewing the audio later. This is worth addressing because it seems like a reasonable third option.

The research is clear: recording without note-taking produces worse outcomes than either handwriting or typing. Students who rely on recordings tend to pay less attention during the lecture (they know they can listen again later) and often never actually review the full recording. A 50-minute lecture takes 50 minutes to re-listen to--far more time than reviewing well-taken notes.

However, recording as a supplement to active note-taking can be useful. If you miss something important, you can fill the gap from the recording. The key is that the recording should support your notes, not replace them.

Making your choice

Here is a decision framework based on the research.

Choose handwriting when:

- You are learning conceptual material for the first time

- The subject involves diagrams, formulas, or spatial reasoning

- You are prone to digital distraction

- The professor bans devices

- Deep processing matters more than comprehensive capture

Choose digital when:

- The lecture is fast-paced and information-dense

- You are building a long-term knowledge system

- The subject is terminology-heavy and you will need to search your notes

- You are collaborating with study groups

- Organization and retrieval are priorities

Choose hybrid when:

- You want the encoding benefits of handwriting AND the organizational benefits of digital

- You have 15-20 minutes after each lecture for processing

- You are taking courses across multiple subjects with different demands

The best note-taking medium is the one that makes you think--not the one that makes you feel productive.

Whatever medium you choose, combine it with consistent review using active recall and spaced repetition. A student who handwrites notes and never reviews them will be outperformed by a student who types notes and reviews them actively every three days. The review matters more than the medium. Track your study sessions to make sure review actually happens rather than remaining a good intention.

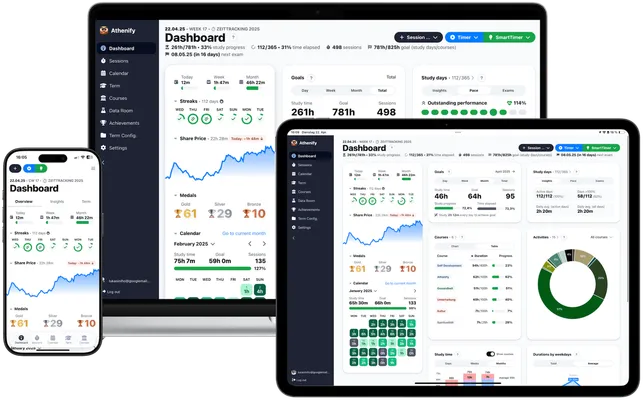

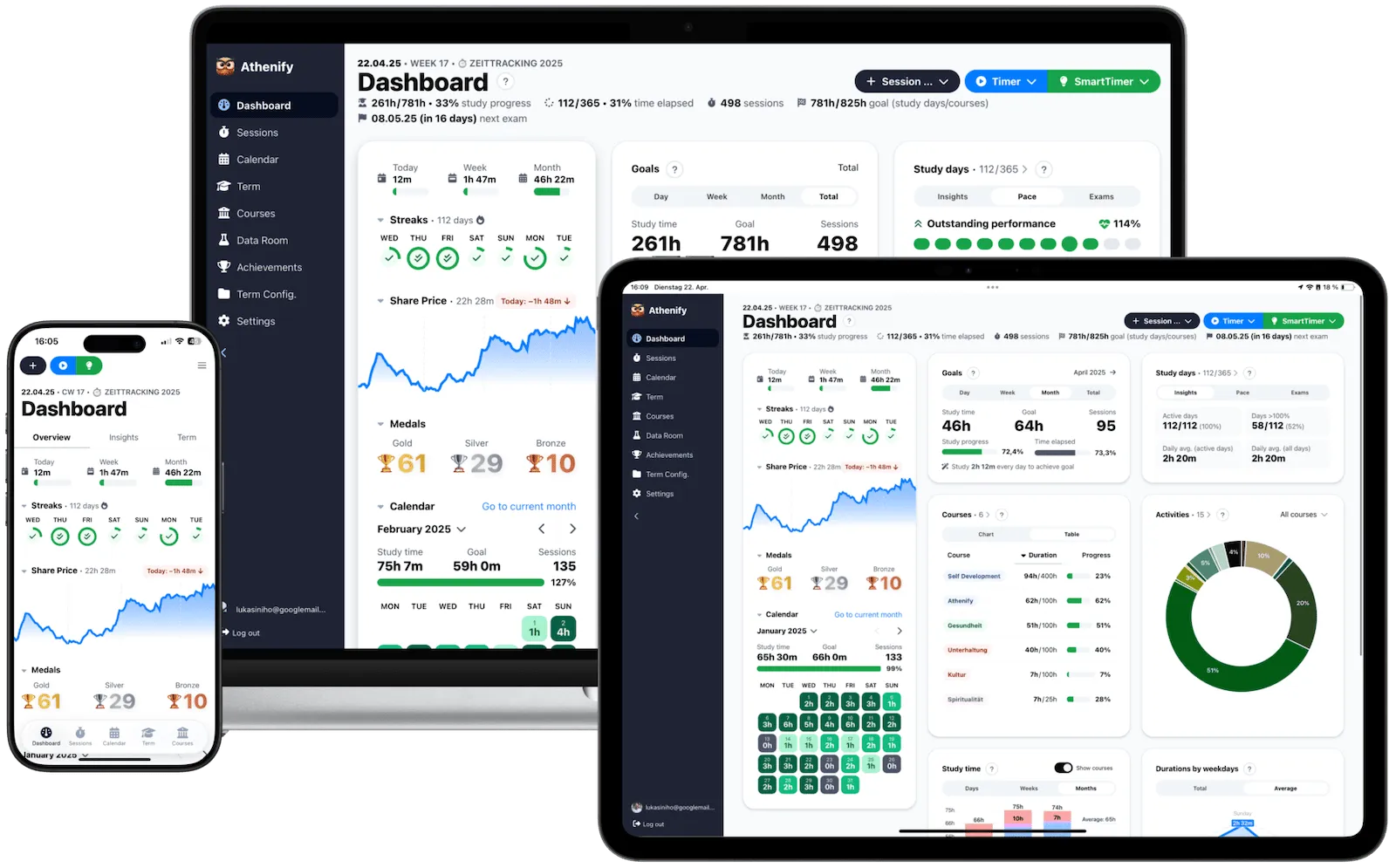

Try Athenify for free

Track your note-taking and review sessions across courses. See where your time goes and build the consistent habits that turn notes into knowledge.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Conclusion

The digital-vs.-handwritten debate is a false binary. The research does not support a universal recommendation for either medium. What it supports is this: the depth of processing during note-taking matters more than the tool you use, handwriting naturally enforces deeper processing, and digital tools offer organizational advantages that compound over time.

Stop asking "pen or laptop?" Start asking "Am I processing or transcribing?" Then choose the tool--or combination of tools--that keeps you on the right side of that question.

The students who perform best are not the ones who picked the "right" medium. They are the ones who matched their tools to their tasks, reviewed their notes consistently, and treated note-taking as an active learning strategy rather than a passive recording exercise.