Why note-taking method matters more than note-taking volume

Most students confuse note-taking quantity with quality. They sit in lectures furiously transcribing every word the professor says, filling page after page, and leave feeling productive. But cognitive science tells a different story. Research on the encoding effect shows that the act of processing information during note-taking is what drives learning -- not the act of recording it. When you simply copy words from a slide to your notebook, you bypass the deep cognitive processing that forms durable memories.

The encoding effect means how you take notes matters far more than how many notes you take.

The external storage effect -- having notes to review later -- only works if those notes are organized in a way that facilitates retrieval and self-testing. A wall of verbatim text is nearly useless for review because it lacks structure, cues, and condensed meaning. Students who take fewer but more thoughtful notes consistently outperform those who transcribe everything. The verbatim transcription trap is one of the most common mistakes in higher education, and escaping it is the single biggest upgrade most students can make to their study habits.

Active processing during note-taking means paraphrasing concepts in your own words, generating questions, and connecting new ideas to what you already know. This is a form of elaborative encoding, one of the most powerful memory strategies identified by cognitive psychologists. When you force yourself to rephrase an idea, you must first understand it -- and that moment of understanding is where real learning happens.

Handwritten vs digital notes: what the research says

The Mueller and Oppenheimer study (2014) changed the conversation about laptops in classrooms. Their research, published in Psychological Science, found that students who took notes on laptops performed significantly worse on conceptual questions than those who wrote by hand -- even though the laptop users recorded more content. The reason was clear: laptop users tended to transcribe lectures verbatim, while hand-writers were forced to select, condense, and paraphrase because they simply could not write fast enough to capture every word.

This advantage is explained by the generation effect -- the well-documented finding that information you generate yourself (by rephrasing, summarizing, or elaborating) is remembered far better than information you passively receive. Handwriting naturally triggers this effect because the physical slowness of pen on paper forces you to think before you write. Your brain must decide what matters most and how to express it concisely.

Handwriting forces deeper processing because you cannot transcribe verbatim — you must summarize and paraphrase in real time. This "generation effect" means handwritten notes, though fewer in quantity, produce superior understanding and retention.

However, digital notes win in other important areas: searchability, reorganization, backup, and multimedia integration. Students with learning disabilities, those in fast-paced STEM courses, or anyone who needs to manage large volumes of reference material may benefit from digital tools. The key insight is that the medium matters less than the method -- our guide on digital vs handwritten notes breaks down the full research. If you type your notes, you must consciously avoid transcription and instead rephrase ideas in your own words. Tools like Notion and Obsidian support structured note-taking methods digitally, letting you combine the best of both approaches with your broader study techniques.

The Cornell method explained

Developed at Cornell University in the 1950s by Professor Walter Pauk, the Cornell note-taking system is one of the most rigorously tested methods in educational research. The system divides your page into three distinct sections: a narrow cue column on the left (about 2.5 inches wide), a wider note-taking area on the right, and a summary section at the bottom of the page. Each section serves a specific cognitive function that builds on the others.

During the lecture, you take notes in the right column using your own words -- paraphrasing, abbreviating, and capturing key ideas rather than transcribing verbatim. Within 24 hours after class, you review those notes and generate questions, key terms, and cue words in the left column. These cues serve as retrieval prompts for self-testing: cover the right column, read a cue, and try to recall the associated information. Finally, write a brief summary at the bottom that condenses the entire page into two or three sentences. For a detailed walkthrough, see our complete Cornell note-taking method guide.

The review step is what makes Cornell notes transformative rather than just organizational. Studies show that students who complete the full Cornell cycle -- notes, cues, and summary -- score up to 29% higher on tests compared to those who take unstructured notes. The method works because it embeds active recall and spaced review directly into the note-taking workflow. You are not just recording information; you are systematically processing it for long-term retention. Cornell notes also make exam preparation dramatically more efficient because the cue column functions as a ready-made self-testing tool.

The Zettelkasten system for deep learning

Niklas Luhmann, a German sociologist, used the Zettelkasten method to produce over 70 books and 400 scholarly articles across an extraordinary range of subjects. His secret was a deceptively simple system: write each idea on a separate note (a "Zettel"), express it in your own words, and link it explicitly to related notes. Over decades, Luhmann built a network of roughly 90,000 interconnected notes -- a "second brain" for deep learning that generated new insights through the connections between ideas.

Sociologist Niklas Luhmann produced over 70 books and 400 scholarly articles using his Zettelkasten — a network of 90,000 interconnected notes. The system's power lies not in individual notes but in the connections between them, which generate new insights through unexpected combinations.

For students, the Zettelkasten method transforms note-taking from a course-by-course activity into a cumulative knowledge-building practice. Each note should be "atomic" -- containing exactly one idea, fully expressed in your own words. When you encounter a concept in your psychology lecture that relates to something from your economics course, you create an explicit link between those notes. Over time, these cross-course connections reveal patterns and principles that isolated studying never uncovers. Learn how to get started in our Zettelkasten for students guide.

The power of Zettelkasten lies in its compounding returns. Unlike traditional notebooks that sit on a shelf after the semester ends, a well-maintained Zettelkasten grows more valuable over time. Each new note you add creates potential connections with everything already in the system, making it easier to write essays, prepare for comprehensive exams, and develop original ideas. Combined with a consistent study schedule, the Zettelkasten method turns your entire academic career into a single, interconnected learning project.

Mind mapping and visual note-taking

Tony Buzan popularized mind mapping in the 1970s, but the underlying principle -- that visual, radial organization aids memory -- has deep roots in cognitive science. A mind map starts with a central concept in the middle of the page, with branches radiating outward for main topics, sub-branches for supporting details, and connections drawn between related ideas. This structure mirrors the associative nature of human memory, where ideas are stored not in linear sequences but in interconnected webs.

Research published in the Journal of Educational Psychology found that mind mapping can improve recall by up to 32% compared to linear notes. The visual layout engages spatial memory, while the act of organizing information into branches requires you to identify hierarchies and relationships -- a form of deep processing that passive transcription completely misses. Color coding, icons, and images further enhance the dual coding effect, where information stored in both verbal and visual forms is remembered significantly better.

Mind mapping is particularly powerful for subjects with complex relationships: biology (systems and processes), history (cause-and-effect chains), literature (thematic connections), and any course that requires synthesizing multiple perspectives. However, mind maps are less effective for highly sequential or quantitative content. The best approach is to use mind mapping strategically -- for brainstorming sessions, chapter overviews, and connecting ideas during review -- while using a more structured method like Cornell for day-to-day lecture notes. Our mind mapping study technique guide walks through the process step by step.

Common note-taking mistakes students make

Verbatim transcription is the most widespread and damaging note-taking mistake. When you copy every word the professor says, your brain operates in "stenographer mode" -- focused on accurate recording rather than understanding. Research consistently shows that students who transcribe verbatim perform worse on conceptual questions despite having more complete notes. The solution is deliberate paraphrasing: force yourself to close the source, recall the main idea, and write it in your own words. For practical strategies, read our guide on how to take effective lecture notes.

Verbatim transcription — writing down everything the lecturer says — is the most common note-taking trap. It feels productive but bypasses the deep processing that creates understanding. Force yourself to paraphrase and you will remember far more.

Never reviewing notes is the second critical mistake. The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve shows that without review, you lose approximately 80% of new information within 24 hours. Taking beautiful, structured notes is worthless if they sit in a drawer until exam week. Build a daily review habit by scheduling short 10 -- 15 minute sessions with a study timer to revisit and condense your most recent notes before the forgetting curve erases them.

Lack of structure turns notes into unusable walls of text. Notes without headings, bullet points, or visual hierarchy are nearly impossible to review efficiently. Always use a consistent format -- whether Cornell, outlining, or another system -- so you can quickly locate and retrieve information. Copying other students' notes is equally problematic because the learning benefit comes from the act of processing, not from possessing the information. Similarly, failing to personalize notes -- adding your own questions, connections, and examples -- turns them into impersonal reference documents that lack the retrieval cues your memory needs.

How Athenify supports your note-taking practice

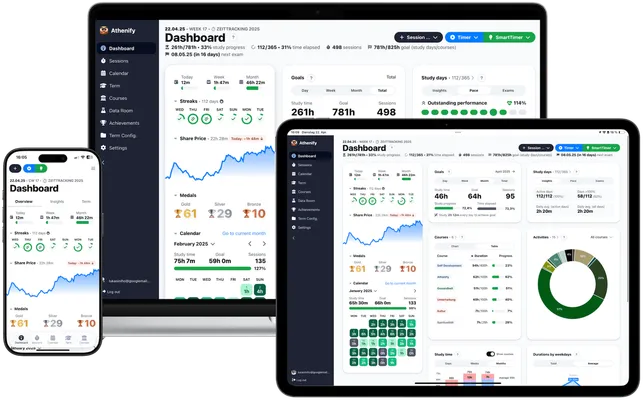

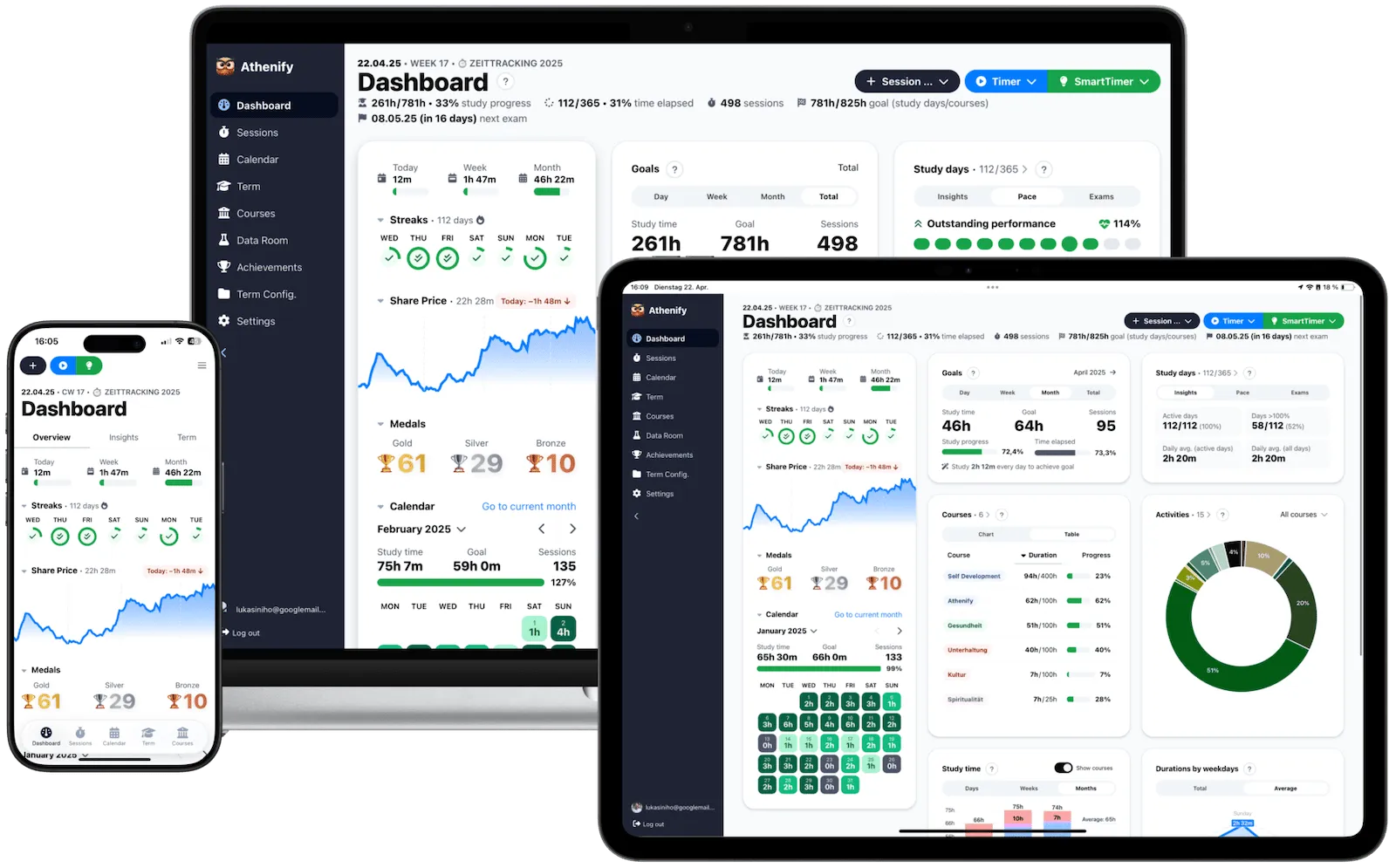

Consistent note review is a habit, and habits need tracking. Athenify helps you build and maintain a daily note review practice through timed study sessions, Pomodoro mode for focused note processing, and streak tracking that rewards consistency. Set a daily goal for note review time, start a session with the study timer, and watch your streak grow as you build the habit that makes all note-taking methods effective.

Beyond timing, Athenify's subject-level tracking shows you exactly which courses need more review attention. If your biology notes haven't been reviewed in a week while your history notes are up to date, the data makes it visible at a glance. Combined with progress visualization that shows your total review hours accumulating over weeks and months, Athenify transforms note review from a vague intention into a measurable, trackable study habit with real accountability.

Getting started: choose your method and commit

The biggest mistake is endlessly researching methods instead of practicing one. Pick the method that resonates most with your learning style -- Cornell for structured review, Zettelkasten for deep connections, mind mapping for visual understanding, or outlining for logical subjects. Then commit to using it exclusively for 30 days before evaluating. Switching methods every few days prevents you from developing the fluency and automaticity that make any system truly effective.

Track your note review sessions daily. Start small -- even 10 minutes of focused review per day is enough to beat the forgetting curve and build momentum. As the habit solidifies, increase your review time and begin connecting notes across subjects. The compound effect of daily, deliberate note-taking practice is extraordinary: students who maintain consistent review habits throughout the semester spend less total time studying while achieving higher grades, because they never have to re-learn forgotten material. Let your notes work for you by reviewing them consistently, and use Athenify to make that consistency visible and rewarding through exam preparation tracking and progress analytics.

Try Athenify for free

Track your note-taking practice with Athenify

No credit card required.

No credit card required.