It is 8 AM. You slept poorly, your first lecture is in an hour, and you have a study session planned for the afternoon. So you do what roughly 85 percent of college students do every single day: you reach for caffeine.

But here is the question almost nobody asks: Are you using caffeine in a way that actually helps your studying? Or are you unknowingly sabotaging your sleep, building tolerance that makes it less effective, and drinking it at times that work against your brain's natural chemistry?

The science on caffeine and cognitive performance is extensive, nuanced, and often contradicts what most students believe. This guide covers what the research actually shows--no marketing, no broscience, just evidence.

Caffeine is the most powerful legal cognitive enhancer available to you. But like any tool, its value depends entirely on how you use it.

How caffeine works in your brain

To use caffeine strategically, you need to understand the mechanism. It is surprisingly simple.

Throughout the day, your brain accumulates a molecule called adenosine. Adenosine binds to receptors in your brain and produces the sensation of drowsiness. The longer you are awake, the more adenosine builds up, and the sleepier you feel. This is called "sleep pressure," and it is one of the two main systems that regulate your sleep-wake cycle.

Caffeine works by blocking adenosine receptors. It does not eliminate adenosine--the molecule keeps building up. Caffeine simply prevents your brain from detecting it. This is why you feel alert after coffee: the drowsiness signal is being masked, not removed.

This mechanism has several important implications for students:

- Caffeine does not create energy. It blocks the signal that tells you to rest. The underlying fatigue is still there, accumulating in the background

- When caffeine wears off, adenosine floods your receptors all at once. This is the "caffeine crash"--the sudden wave of tiredness when the blocking effect ends

- Caffeine has a half-life of 5 to 6 hours. If you drink 200 milligrams of caffeine at 2 PM, you still have 100 milligrams active at 7 or 8 PM. This matters enormously for sleep

What caffeine actually does for studying

The research on caffeine and cognitive performance is remarkably consistent. Here is what it reliably improves:

Alertness and vigilance

This is caffeine's primary benefit. Multiple meta-analyses confirm that caffeine significantly improves sustained attention and reduces the performance decline that comes with prolonged mental effort. For students facing long study sessions, this is the most relevant effect.

Working memory

Moderate caffeine intake (100 to 200 milligrams) improves performance on working memory tasks. Working memory is the cognitive system that holds and manipulates information in the short term--exactly what you use when solving problems, following complex arguments, or connecting ideas across a reading.

Reaction time

Caffeine consistently improves reaction time across studies. While this matters less for studying than for, say, driving, it does mean your cognitive processing speed increases--you read slightly faster and respond to mental challenges more quickly.

Mood

Caffeine has mild mood-enhancing effects, reducing perceived fatigue and increasing subjective feelings of energy and well-being. When studying feels like a slog, a cup of coffee genuinely does make the experience more pleasant.

The optimal caffeine strategy for students

Based on the research, here is how to use caffeine as an effective study tool rather than a mindless habit.

Dose: 100 to 200 milligrams

This is the range where cognitive benefits are strongest and side effects (anxiety, jitteriness, increased heart rate) are minimal. Above 200 milligrams in a single dose, the anxiety-increasing effects often cancel out the focus-improving effects.

| Source | Approximate caffeine content |

|---|---|

| Espresso (single shot) | 63 mg |

| Brewed coffee (240 ml / 8 oz) | 95 mg |

| Black tea (240 ml / 8 oz) | 47 mg |

| Green tea (240 ml / 8 oz) | 28 mg |

| Energy drink (250 ml can) | 80 mg |

| Cola (355 ml / 12 oz) | 34 mg |

| Dark chocolate (30 g) | 23 mg |

Timing: align with your cortisol cycle

Your body naturally produces cortisol--a hormone that promotes alertness--in a predictable daily pattern. Cortisol peaks during the first 30 to 60 minutes after waking (the "cortisol awakening response"), then again around midday.

Drinking caffeine during a cortisol peak is partially redundant. You are already alert. The optimal time for caffeine is when cortisol dips:

- 90 to 120 minutes after waking: Your first cortisol peak has passed. Caffeine will provide a genuine boost rather than stacking on top of natural alertness

- Early afternoon (1 to 2 PM): Cortisol typically dips after lunch, and this is when many students experience the "afternoon slump." A moderate caffeine dose here can restore focus for afternoon study sessions

The hard cutoff: no caffeine after 1 to 2 PM

This is the most important rule and the one students most frequently violate.

Caffeine has a half-life of 5 to 6 hours, meaning half of it is still in your bloodstream after that time. If you drink coffee at 4 PM, you still have a quarter of that caffeine active at midnight. Research using sleep-tracking technology shows that afternoon caffeine--even when subjects feel they sleep normally--reduces deep sleep duration by up to 20 percent.

The caffeine you drink at 4 PM is not helping you study tonight. It is stealing the sleep that would help you study better tomorrow.

Deep sleep is when your brain consolidates memories and transfers information from short-term to long-term storage. Reducing deep sleep by even 20 percent means you retain significantly less of what you studied that day. This is the cruel irony of late-afternoon caffeine: it makes you feel productive in the moment while undermining the very process that turns studying into lasting knowledge.

For an in-depth look at the connection between sleep and academic performance, see our guide on how sleep affects learning.

Caffeine and sleep: the trade-off students ignore

Most students dramatically underestimate caffeine's impact on their sleep. In a landmark study, researchers gave subjects 400 milligrams of caffeine at three different times: at bedtime, 3 hours before bed, and 6 hours before bed. Even the 6-hours-before group experienced significant sleep disruption.

Here is what makes this particularly insidious: many students do not feel that their sleep was disrupted. They fall asleep at their normal time and wake up at their normal time. But sleep-tracking data reveals reduced deep sleep, more frequent micro-awakenings, and lower overall sleep quality. The result is feeling unrested and reaching for more caffeine the next morning--creating a cycle that progressively worsens both sleep and cognitive performance.

The caffeine-sleep debt cycle

- Poor sleep the night before leads to fatigue

- Student consumes caffeine to compensate

- Caffeine consumed too late disrupts that night's sleep

- The next morning, fatigue is even worse

- Student consumes even more caffeine

- Repeat

Breaking this cycle requires one uncomfortable week: reduce caffeine to one cup before noon and accept that you will feel more tired for 3 to 5 days while your sleep quality recovers. After that adjustment period, most students report feeling more alert with less caffeine because their sleep has improved.

Coffee versus tea for studying

Students often debate whether coffee or tea is better for studying. The answer depends on what type of work you are doing.

Coffee: the intensity tool

Coffee delivers a fast, strong caffeine hit. Blood caffeine levels peak 30 to 60 minutes after consumption and provide maximum alertness for about 2 to 3 hours. This makes coffee ideal for:

- Morning deep work sessions requiring maximum concentration

- Intensive problem-solving or writing

- Short, focused study sprints using the Pomodoro technique

The downside is the crash. As caffeine wears off, the accumulated adenosine floods your receptors, and alertness drops sharply. This is why many students feel they need a second cup.

Tea: the sustained focus tool

Tea contains less caffeine per cup (28 to 47 milligrams versus 95 milligrams for coffee) but also contains L-theanine, an amino acid that promotes a state of calm alertness. L-theanine increases alpha brain wave activity, which is associated with relaxed focus--the state where you are alert but not anxious.

The combination of caffeine and L-theanine in tea has been studied extensively:

- Improved attention on demanding cognitive tasks

- Reduced anxiety compared to caffeine alone

- Smoother, longer-lasting energy without the sharp crash

- Better performance on tasks requiring both speed and accuracy

This makes tea ideal for:

- Afternoon review sessions

- Reading-intensive studying

- Any study task where anxiety might impair performance (exam prep, for instance)

- Long sessions where sustained, gentle focus is more valuable than peak intensity

Caffeine tolerance: why your coffee stopped working

If your daily coffee barely seems to wake you up anymore, you have built a tolerance. Here is what happened.

When you consume caffeine regularly, your brain responds by producing more adenosine receptors. More receptors means more landing spots for adenosine, which means you need more caffeine to block the same proportion of them. Within 7 to 12 days of daily use, most people develop significant tolerance.

At full tolerance, caffeine no longer provides a boost above your baseline alertness. It merely brings you back to the level of alertness you would have had naturally if you had never started consuming caffeine in the first place. Your morning coffee is not making you sharp. It is preventing withdrawal symptoms from making you sluggish.

How to reset your caffeine tolerance

A caffeine tolerance reset takes 7 to 10 days of reduced or eliminated caffeine intake.

The gradual approach (recommended):

- Day 1 to 3: Reduce intake by half

- Day 4 to 6: Reduce to one quarter of your normal intake

- Day 7 to 10: Zero caffeine or just a single cup of green tea

After the reset:

- Reintroduce caffeine at the minimum effective dose (one cup of coffee)

- Use it strategically rather than habitually

- Aim for 2 to 3 caffeine-free days per week to prevent tolerance from rebuilding

The first few days of a reset are uncomfortable--expect headaches and fatigue. Schedule your reset during a low-demand academic period. The payoff is that caffeine becomes genuinely effective again.

Common caffeine mistakes students make

Mistake 1: Using caffeine to replace sleep

No amount of caffeine can replicate what sleep does for your brain. Sleep consolidates memories, clears metabolic waste, and restores cognitive function in ways that caffeine cannot. A caffeinated but sleep-deprived student will consistently underperform compared to a well-rested one.

Mistake 2: Drinking caffeine on an empty stomach

Caffeine stimulates stomach acid production. On an empty stomach, this can cause nausea, jitteriness, and anxiety--symptoms that actively impair studying. Always consume caffeine with or after food for a smoother, more sustained effect.

Mistake 3: Relying on energy drinks

Energy drinks combine excessive caffeine with large amounts of sugar and questionable additives. The sugar crash that follows an energy drink often leaves you more fatigued than before. A cup of black coffee or green tea provides the same cognitive benefits without the crash, the cost, or the excessive sugar.

Mistake 4: Ignoring individual variation

Caffeine sensitivity varies enormously between individuals. Some people metabolize caffeine twice as fast as others due to genetic differences. If a single cup of coffee makes you anxious and jittery, you are likely a slow metabolizer. Reduce your dose or switch to tea. There is no virtue in consuming caffeine that makes you feel worse.

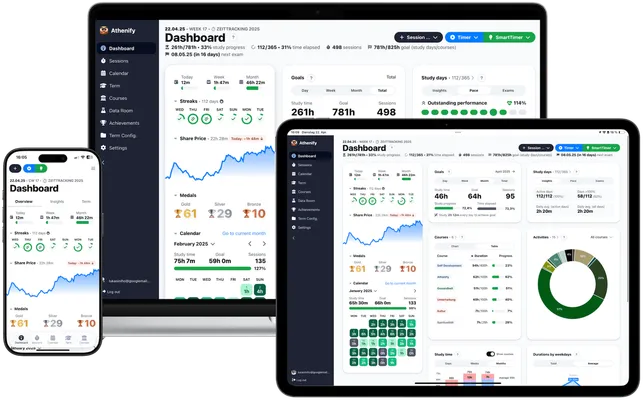

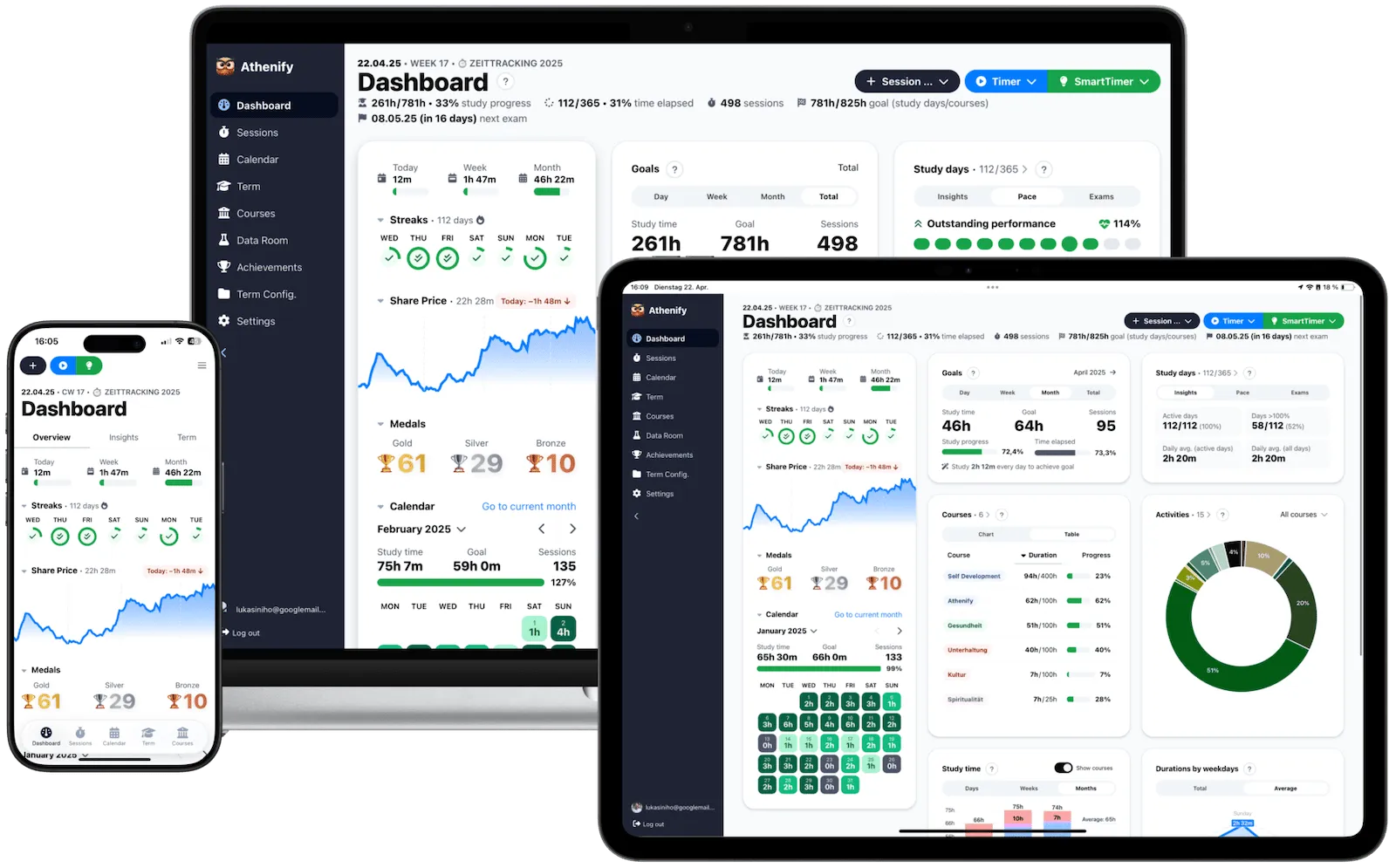

Try Athenify for free

Track your study sessions to see how caffeine timing affects your focus. Athenify helps you discover when you do your best work.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

The bottom line

Caffeine is a legitimate cognitive tool--one of the few legal substances with robust evidence for improving alertness, working memory, and sustained attention. But it is a tool, not a solution.

Used well, caffeine amplifies an already solid study routine: it sharpens your focus during dedicated study blocks, helps you push through afternoon energy dips, and makes the act of studying slightly more pleasant. Used poorly, it disrupts your sleep, builds tolerance until it barely works, and creates a dependency cycle that makes you feel worse over time.

The evidence points to a simple strategy: one to two cups of coffee or tea, consumed between 90 minutes after waking and early afternoon, with a hard cutoff at least 8 hours before bedtime. Pair this with good sleep, regular exercise, and a well-designed study environment, and you have a caffeine practice that genuinely enhances your learning.

The best study aid is not a stronger cup of coffee. It is a better night's sleep.

Stop treating caffeine as a substitute for the fundamentals. Start treating it as the finishing touch on a system that already works. Your brain will thank you.