You study hard for an exam. You pass. A month later, you can barely remember what you learned. Sound familiar? This isn't a personal failing—it's how human memory works. Without intervention, we forget approximately 70% of new information within 24 hours, and 90% within a week. But there's good news: scientists have discovered how to hack the forgetting curve. The technique is called spaced repetition, and it can transform how much you retain from your studies.

The best time to review something is right before you forget it.

The forgetting curve problem

In 1885, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus conducted a groundbreaking experiment: he memorized lists of nonsense syllables and tested how quickly he forgot them. His findings—still replicated in laboratories today—revealed what he called the forgetting curve.

The decay is dramatic and swift. After just 20 minutes, you retain only 58% of what you learned. An hour later, that drops to 44%. By the next day, you're down to 33%, and after a week, only about a quarter remains. A month out, you're holding onto just 21% of the original material.

| Time elapsed | Typical retention |

|---|---|

| 20 minutes | 58% |

| 1 hour | 44% |

| 1 day | 33% |

| 1 week | 25% |

| 1 month | 21% |

This is why cramming produces poor long-term results. You might remember enough for tomorrow's exam, but the knowledge rapidly decays. The forgetting curve seems depressing—but Ebbinghaus discovered something else that changed everything: each review resets and flattens the curve. Review at the right times, and you can remember almost anything indefinitely.

"Learning is not the number of times you've seen something—it's the number of times you've successfully retrieved it from memory."

— Robert Bjork, cognitive psychologist

How spaced repetition works

Spaced repetition exploits a psychological phenomenon called the spacing effect: information reviewed across multiple sessions, spaced apart in time, is remembered far better than information reviewed in a single massed session. It's one of the most powerful study techniques for long-term retention.

The science behind spacing

When you learn something new, your brain creates a memory trace—a pattern of neural connections. This trace is initially weak. Without reinforcement, it fades. Here's the counterintuitive part: the best time to review is when you're about to forget.

Why? Because difficult retrieval—remembering something at the edge of forgetting—strengthens the memory trace more than easy retrieval. If you review too soon (when memory is still strong), you're not working hard enough. If you review too late (after you've forgotten), you have to relearn from scratch.

Spaced repetition finds the sweet spot: review just before forgetting, when retrieval is challenging but still possible.

Memory works by desirable difficulty. The harder you work to remember, the stronger the memory becomes.

The spacing effect in action

Consider two students studying the same material for a Monday exam. Student A crams everything on Sunday night, reviewing all material in one intensive session. She passes Monday's exam—barely—and moves on. Student B takes a different approach: she studies the material on Wednesday, reviews it on Thursday (one day later), and reviews again on Sunday (three days later) before taking Monday's exam.

Both students invest similar total time. But here's what happens two weeks later:

| Student | Retention after 2 weeks |

|---|---|

| Student A (crammed) | ~20% |

| Student B (spaced) | ~80% |

The difference is staggering—and it compounds over time. Student B will need only a brief review to refresh her knowledge for finals, while Student A will essentially start from scratch.

Spaced repetition schedules

The exact intervals matter less than the principle, but research has converged on a commonly used schedule that works well for most learners.

Basic schedule

| Review number | Interval |

|---|---|

| 1st review | 1 day |

| 2nd review | 3 days |

| 3rd review | 1 week |

| 4th review | 2 weeks |

| 5th review | 1 month |

| 6th review | 2 months |

If you struggle with an item during review, reset the interval to the beginning. If it's easy, you can extend intervals further.

Adjusting for difficulty

Not all material is equally difficult, and your spacing should reflect that:

- Easy recall (answer came instantly) – Extend the next interval beyond schedule, perhaps from 3 days to 5 days.

- Difficult recall (got it right, but it took effort) – Shorten the next interval slightly to reinforce the shaky memory.

- Failed recall (couldn't remember) – Reset to the beginning with a one-day interval.

Modern spaced repetition software calculates these adjustments automatically based on your responses, learning your personal forgetting patterns for each piece of information.

Tools for spaced repetition

You can implement spaced repetition with nothing more than physical flashcards and a box system, but digital tools make the process dramatically easier. They handle the scheduling automatically, track your performance over time, and ensure you never miss a review that's due.

Digital flashcard apps

Anki is the gold standard for serious spaced repetition users. It's free on desktop and relatively inexpensive on mobile, with powerful customization options that let you tune the algorithm to your learning style. The software calculates optimal review times based on your performance, adjusting intervals automatically when you struggle with a card or find it easy. There's a huge library of pre-made decks for everything from language learning to medical school exams, and it works offline for studying anywhere.

The learning curve can be steep for beginners, but the investment pays dividends. Medical students, language learners, and law students swear by Anki precisely because it works.

Quizlet offers a gentler introduction with a simpler, more intuitive interface. The "Learn" mode uses spaced repetition principles to optimize your review sessions, and the platform excels at sharing decks with study groups—useful for collaborative exam preparation. The free tier has limitations, but it's enough to get started and see if digital flashcards work for you.

Other options worth considering include RemNote (combines note-taking with flashcards), Brainscape (confidence-based repetition), SuperMemo (the original spaced repetition software), and Mochi (markdown-based cards for technical content).

Manual tracking with the Leitner system

Don't want to use an app? You can implement spaced repetition manually using the Leitner box system, developed by German science journalist Sebastian Leitner in the 1970s. Create physical flashcards and divide them into five boxes. Box 1 gets reviewed daily, Box 2 every three days, Box 3 weekly, Box 4 bi-weekly, and Box 5 monthly. When you successfully recall a card, it moves up to the next box. When you fail, it drops back to Box 1 regardless of where it started. This simple system approximates the benefits of algorithmic spacing without any technology.

Tracking your sessions

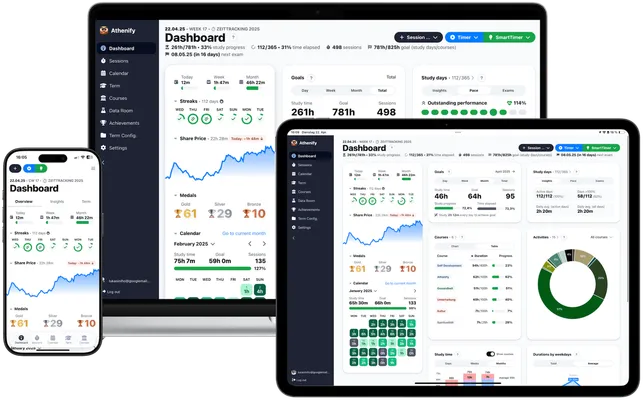

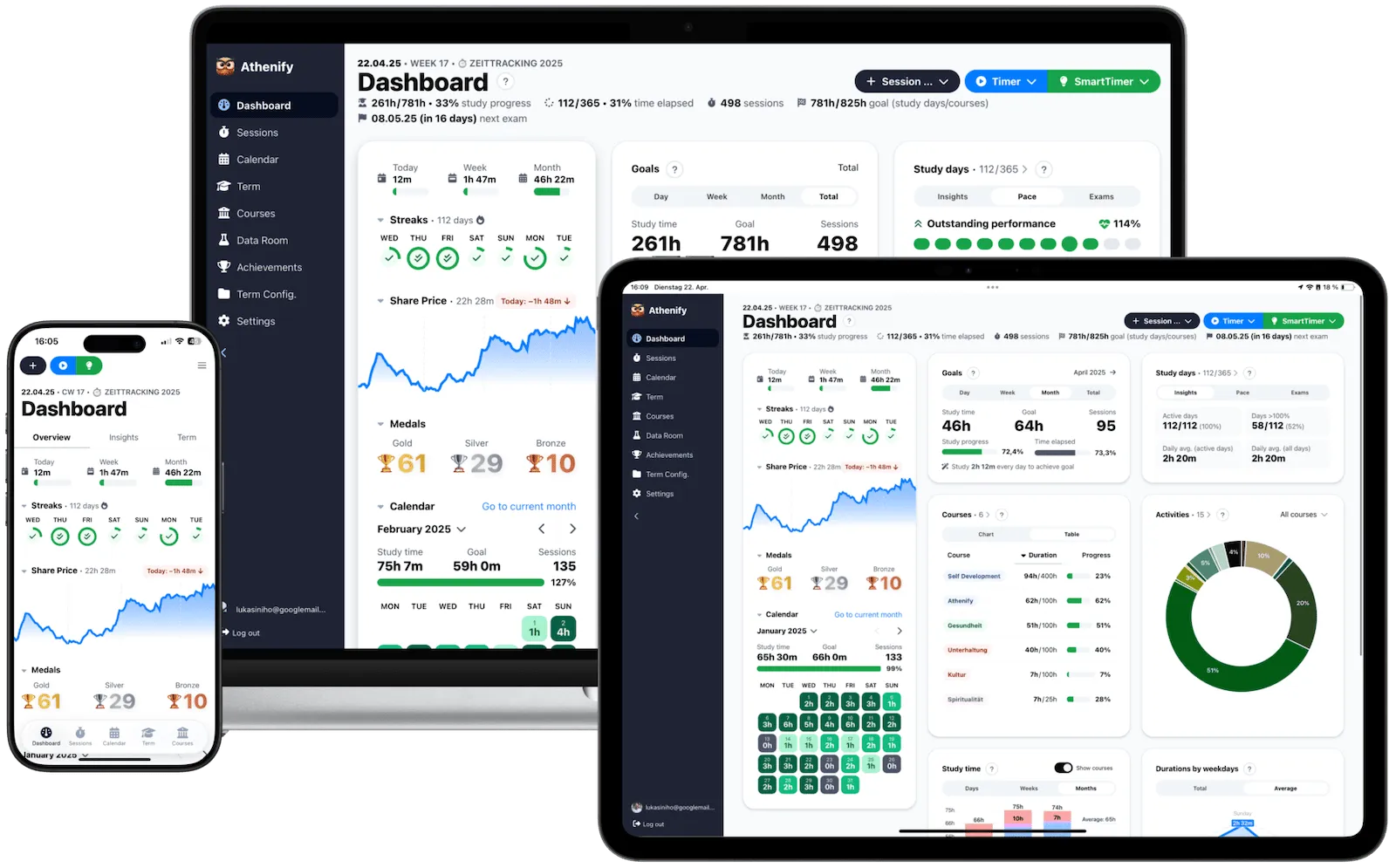

Whatever method you use, tracking study time creates accountability. When you log your spaced repetition sessions with Athenify, you can see patterns: which subjects get consistent review, how your total study hours accumulate, whether you're maintaining your review schedule.

Try Athenify for free

Track your review sessions, build daily streaks, and see which subjects need more attention—all in one place.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Spaced repetition only works if you actually do the reviews. Tracking keeps you accountable.

Creating effective flashcards

Spaced repetition is only as good as the material you're reviewing. Poor flashcards produce poor results.

Principles for good flashcards

Keep cards atomic. Each card should test exactly one fact or concept. Don't try to pack multiple ideas together—this makes cards harder to review and provides less precise feedback about what you actually know. Instead of creating a monster card about "Mitochondria: produces ATP through oxidative phosphorylation in the inner membrane using the electron transport chain," break that into several simple cards: "What organelle produces ATP?" → "Mitochondria."

Use active recall. Cards should require you to produce an answer from memory, not just recognize whether something is true. A yes/no card like "Is ATP produced by mitochondria?" doesn't work your memory nearly as hard as "What is the main function of mitochondria?" The act of production—pulling information from your memory rather than simply confirming it—is what strengthens the memory trace.

Add context. Pure facts without context are hard to remember and often useless in practice. Connect information to meaning. Instead of a card that just says "1789," create one that asks "When did the French Revolution begin, and what triggered it?" The additional context gives your brain more hooks to hang the memory on.

Include both directions. For vocabulary and definitions, create cards in both directions. One card shows "Mitochondria" and asks for the definition; another shows "Which organelle produces ATP?" and asks for the term. This builds stronger, more flexible knowledge.

What to put on flashcards

Flashcards excel at cementing factual knowledge that needs to become automatic:

- Vocabulary and definitions

- Dates and historical facts

- Formulas and equations

- Foreign language phrases

- Anatomical terms and medical terminology

- Legal cases and precedents

They're less suited for complex problem-solving (use practice problems), deep conceptual understanding (use active recall and explanation), or skills requiring practice (use deliberate practice). Think of flashcards as the foundation—they ensure you have ready access to the building blocks, but you still need to practice assembling them. Consider organizing all your learning materials in a second brain system to complement your spaced repetition practice—the Zettelkasten method is particularly well suited for building a networked knowledge base alongside your flashcard reviews.

Combining spaced repetition with other techniques

Spaced repetition + active recall

These techniques are natural partners. Spaced repetition tells you when to review; active recall tells you how. Every flashcard review should be a genuine active recall attempt: see the prompt, genuinely try to recall the answer (resist the urge to flip early), compare your answer to the correct one, and mark honestly about whether you really knew it. The temptation to peek or to mark "correct" when you sort of knew it undermines the entire system.

Spaced repetition + elaborative encoding

When you first learn material, don't just read it—elaborate on it. Connect to what you already know. Create mental images. Generate examples. Explain why it makes sense. This elaborative encoding creates richer memory traces with more connections to your existing knowledge. Spaced repetition can then maintain these well-formed memories over time. Poor initial encoding means spaced repetition has less to work with.

Spaced repetition + time tracking

Track both your total study time for a subject and your spaced repetition review time specifically. This reveals whether you're balancing new learning with maintenance. If review time crowds out everything else, you've added too many cards. If you never review, you're building on a foundation of sand. The ideal balance shifts over a semester—more new learning early, more review as exams approach. For optimal focus during review sessions, try using the Pomodoro Technique or schedule your reviews during deep work blocks.

Common spaced repetition mistakes

The five most common mistakes that derail spaced repetition:

- Adding too many cards – Every card creates future review obligations that compound over time. Enthusiastic beginners often add 50–100 cards at once, then drown in reviews a week later. Start small; scale up only when you can comfortably maintain your queue.

- Skipping review sessions – Consistency matters more than volume. Missing a week creates a backlog that's discouraging to face. The cards don't go away—they pile up with increasingly urgent due dates.

- Rating cards too generously – If you click "Easy" when you barely remembered, the software spaces reviews too far apart and you forget. Be honest: if it was hard, mark it hard.

- Creating overly complex cards – If a card regularly takes more than 10 seconds to answer, it's too complex. Break it into multiple simpler cards.

- Only using flashcards – Flashcards are one tool, not a complete learning system. You still need to understand concepts deeply, practice applying knowledge, and engage with material in varied ways.

Spaced repetition for different subjects

Languages are perhaps the ideal use case for spaced repetition. Vocabulary acquisition is pure memorization, and there's a lot of it. Include word-translation pairs in both directions, example sentences with cloze deletions, audio for pronunciation when available, and images for concrete nouns. The combination of visual, auditory, and contextual information creates robust memories.

Medicine and science rely heavily on terminology, anatomical structures, drug mechanisms, and diagnostic criteria. Medical students swear by Anki—there are massive pre-made decks for USMLE, MCAT, and nursing exams. The sheer volume of factual knowledge required makes spaced repetition essential rather than optional.

History and social sciences involve key dates, figures, events, and concepts. The key is adding context to prevent isolated facts from floating free of meaning: "What caused X?" "What were the consequences of Y?" "How does A relate to B?"

Math and physics students often use spaced repetition for formulas, theorems, and key problem-solving steps. But supplement heavily with actual problem practice—knowing a formula isn't the same as knowing when and how to apply it.

Law students create cards during case briefing, then review throughout the semester: case names, holdings, legal principles, statutory language. By the time finals arrive, the foundational knowledge is automatic, freeing cognitive resources for analysis.

Getting started: a practical guide

Starting spaced repetition is simple, but building a sustainable habit takes deliberate effort over several weeks.

Week 1 setup checklist:

- Choose your tool – Anki for serious use, Quizlet for a gentler start

- Pick one subject – Don't overwhelm yourself at the beginning

- Create 20–30 cards from recent material — good lecture notes make this step much easier

- Set a daily review time – Same time each day works best (it becomes automatic faster)

Building this routine is key to developing lasting study habits that stick.

During weeks two through four, your job is building the habit. Do your reviews every day without exception—this is non-negotiable. Add 10–15 new cards daily, no more. Track your sessions to stay accountable. If you're failing too many cards, simplify them. If you're breezing through everything, make cards more challenging or add more.

From month two onward, expand and refine. Add more subjects once the first one feels sustainable. Delete or revise cards that consistently cause problems—some material just doesn't work as flashcards. Experiment with advanced card formats like cloze deletion or image occlusion. Review your analytics to optimize practice.

Conclusion: Beat the forgetting curve

The students who remember most aren't studying more—they're reviewing smarter.

Spaced repetition transforms how you retain information. The core insight is simple: you forget 70% of new information within a day without review, but strategically timed reviews can flatten the forgetting curve almost indefinitely. Review new material after 1 day, then 3 days, then 1 week, then 2 weeks, then monthly. Create atomic flashcards testing one concept each, genuinely trying to recall answers before checking. Be consistent—small daily reviews beat sporadic cramming every time. And track your progress, because accountability keeps you on schedule.

The knowledge you build with spaced repetition stays with you—not just until the exam, but for years afterward. That's the kind of learning worth investing in.