You sit in lecture, pen moving furiously across the page. An hour later, you have six pages of notes that somehow contain everything the professor said—and nothing you actually understand. Sound familiar? Most students know how to write things down. Far fewer know how to take notes that actually help them learn.

The problem isn't effort—it's method. Different subjects demand different approaches, and what works for your history seminar might fail spectacularly in organic chemistry. This guide covers the five most effective note-taking methods, when to use each one, and how to transform your notes from passive records into active learning tools.

The goal of note-taking isn't to record information—it's to process it.

The Cornell Method: built-in review system

The Cornell Method, developed at Cornell University in the 1950s, remains one of the most effective systems for lecture-based courses. Its power lies in the structure: rather than filling pages randomly, you create a built-in review system as you write.

How it works

Divide your page into three sections before class begins:

- Note-taking column (right side, ~6 inches wide) – Your main lecture notes go here during class

- Cue column (left side, ~2.5 inches wide) – Leave this blank during lecture; fill it afterward with questions, keywords, and prompts

- Summary section (bottom, ~2 inches tall) – Write a brief summary after class

During the lecture, take notes in the right column as you normally would. Don't worry about perfection—capture main ideas, definitions, formulas, and examples.

The magic happens after class. Within 24 hours, review your notes and create cues in the left column. Turn main ideas into questions: if your notes say "Photosynthesis converts light energy to chemical energy," your cue might be "How does photosynthesis convert energy?" Add keywords that trigger recall of larger concepts.

Finally, write a 2–3 sentence summary at the bottom. This forces you to identify the core message of the lecture—what you'd tell a friend who missed class.

Why it works

The Cornell Method works because it builds review into the note-taking process itself. The cue column transforms passive notes into a self-testing tool. Cover the right side, read a cue, and try to recall the corresponding information. This active recall strengthens memory far more effectively than re-reading—a foundational principle of effective study techniques.

Best for

The Cornell Method shines in lecture-heavy courses like history, psychology, and political science—anywhere you're receiving dense verbal information that requires later recall. It's particularly valuable for students who know they should review but struggle with the discipline to actually do it. The built-in cue column creates an accountability structure: if you haven't filled in those questions, you haven't really finished your notes.

Step-by-step Cornell setup

- Draw a vertical line ~2.5 inches from the left edge

- Draw a horizontal line ~2 inches from the bottom

- During class: take notes in the large right section only

- Within 24 hours: add questions and keywords to the left column

- Write a summary in the bottom section

- To review: cover the right column and answer your cue questions

Mind mapping: visualizing connections

Linear notes work well for linear content. But some subjects—philosophy, literature, strategic thinking—are inherently non-linear. Ideas connect in webs, not chains. For these subjects, mind mapping captures relationships that traditional notes miss.

How it works

Start with the central topic in the middle of a blank page. Draw branches outward for main themes or concepts. From each branch, add sub-branches for supporting details, examples, and connections. Use colors to distinguish categories. Add drawings or symbols where helpful.

The key difference from outlining: connections can cross branches. If a concept from one branch relates to another, draw a linking line. This visual representation of relationships is the method's primary strength.

Why it works

Mind maps mirror how the brain naturally associates ideas—radially, not linearly.

Mind mapping engages visual-spatial processing, which strengthens encoding. The act of deciding where to place a concept—and what it connects to—requires deeper processing than simply writing it down. When you review, the visual layout helps you reconstruct relationships.

Best for

Mind mapping thrives in conceptual, discussion-based subjects where ideas don't follow a neat linear path—philosophy seminars, literature analysis, strategic planning. It's also an exceptional tool for brainstorming essay structures and synthesizing material from multiple sources into a unified whole. If you've ever been told you're a "visual learner" and found traditional notes frustrating, mind mapping may finally feel like a method that matches how your brain naturally works.

Mind mapping in practice

- Place the lecture topic or chapter title in the center

- As major themes emerge, create main branches (use different colors)

- Add sub-branches for supporting details and examples

- Draw cross-connections between related concepts on different branches

- After class: review the map and add any missing connections

- Use your completed map as a one-page summary for exam review

The outline method: hierarchical clarity

For subjects with clear structure—biology classifications, historical timelines, legal frameworks—the outline method provides unmatched clarity. It's the fastest method for capturing hierarchical information and the easiest to review.

How it works

Use indentation to show relationships between ideas:

I. Main Topic

A. Subtopic

1. Supporting detail

2. Supporting detail

a. Example

b. Example

B. Another subtopic

Each level of indentation represents a level of specificity. Main points sit flush left. Supporting details indent one level. Examples and evidence indent further.

Why it works

Outlining forces you to identify relationships in real-time. Is this new point a main idea or a supporting detail? Does it belong under the previous heading or start a new one? These micro-decisions require active processing—you can't outline on autopilot.

The structure also makes review efficient. Scan main headings for a topic overview. Drill into subpoints for detail. The hierarchy mirrors how textbooks and exams often organize information.

Best for

The outline method excels wherever content has natural hierarchy—biology with its kingdom-phylum-class-order cascades, chemistry with its periodic organization, law with its nested rules and exceptions. It's also the fastest method for capturing information, making it ideal for those rapid-fire lecturers who seem to speak without pausing for breath. When structure is inherent in the material, outlining simply mirrors what's already there.

Outline method tips

Speed matters with outlining, so develop a consistent set of abbreviations you use every time—"w/" for "with," "bc" for "because," "def" for "definition," and so on. Leave generous space between sections; you'll inevitably need to add details later as you review. Use consistent markers throughout (Roman numerals for main topics, letters for subtopics, numbers for details), and always review within 24 hours to fill gaps while the lecture is still fresh in your mind.

The boxing method: visual separation

The boxing method (also called the "split-page" or "cell" method) works brilliantly when lectures cover multiple distinct topics that don't connect to each other. Instead of one continuous flow, you create separate "boxes" for each topic on your page.

How it works

When the lecture shifts to a new topic, draw a box around the previous content and start fresh in a new area of the page. Each topic gets its own contained space. Boxes can be different sizes based on content importance.

Why it works

Boxing creates visual chunking—a cognitive principle that helps memory. When you review, you can see at a glance how many distinct topics the lecture covered and where each one lives on the page. It also prevents the confusion of running topics together.

Best for

Boxing works brilliantly for lectures that cover multiple unrelated topics in sequence—survey courses that jump from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution, introductory law classes that discuss three unrelated cases in one session. The visual separation prevents the most common confusion in such courses: blending topics together when you review. If you've ever walked into an exam and mixed up two concepts that happened to be discussed on the same day, boxing solves that problem.

Boxing in practice

- Start your first topic anywhere on the page

- When the topic shifts, draw a box around what you've written

- Label the box with the topic name

- Start the new topic in a fresh area

- Continue boxing as topics change

- Review by topic, not by page

Flow-based note-taking: capturing thinking

Flow notes capture how you think, not just what you hear.

Developed by Cal Newport and others, flow-based note-taking abandons the goal of recording everything. Instead, you capture only what sparks your thinking—ideas, connections, questions, and insights. The page becomes a map of your thought process during the lecture, not a transcript of the lecturer's words.

How it works

Write ideas in clusters rather than linear sequences. When something interests you, write it down and add your own thoughts beside it. Draw arrows to show connections. Ask questions in the margins. Skip details you can get from the textbook—focus on capturing what clicks in your mind during the lecture.

Why it works

Most students try to capture too much. They transcribe rather than process, creating beautiful notes they don't understand. Flow-based notes flip this: you can't write something down unless you're thinking about it. The notes are inherently processed because they reflect your engagement, not the lecture's content.

Best for

Flow-based notes work best when you already have foundational knowledge in the subject—enough context to distinguish important ideas from details. They're particularly effective for problem-solving courses like math, physics, and programming, where understanding the why behind each step matters more than recording the steps themselves. They're also a revelation for students who recognize themselves as chronic over-transcribers: people who write down everything the professor says but understand almost none of it. If that's you, flow notes force a different approach entirely.

Flow notes in action

- Write the lecture topic at the top

- When something interests you, write it as a node

- Add your own thoughts, questions, and connections around it

- Draw arrows between related ideas

- Ignore details you can find in the textbook

- After class: compare with textbook to fill critical gaps

Digital vs. handwritten: the great debate

Research consistently shows handwritten notes produce better learning outcomes, at least for conceptual material. But digital notes offer undeniable advantages for organization, search, and long-term reference. The answer isn't one or the other—it's knowing when to use each.

The case for handwriting

When you write by hand, you can't transcribe verbatim—you're too slow. This limitation is actually a feature: it forces you to process, summarize, and select what's important. The physical act of writing also engages different neural pathways than typing, strengthening encoding.

The slowness of handwriting is a feature, not a bug—it forces you to think.

Handwriting wins when you're learning conceptual material for the first time, when deep understanding matters more than coverage, and—critically—when you notice yourself slipping into transcription mode. The slowness is the feature: it forces selection and processing. Of course, some classes have made the choice for you by banning laptops entirely.

The case for digital

Digital notes excel at organization, search, and integration with other systems. You can link notes together, tag them by topic, search across years of material, and reorganize without rewriting. For building a second brain that serves you beyond a single exam, digital has clear advantages.

Digital wins for long-term knowledge management—when you need to search across years of notes, link related concepts together, or integrate with flashcard systems and other study tools. It's also simply faster when volume matters, and essential for subjects heavy with technical terminology that you'll need to search and reference repeatedly.

The hybrid approach

Many successful students use both, and the combination is often more powerful than either alone. The workflow: take notes by hand during lecture, forcing yourself to process and summarize in real-time. Then, within 24 hours, digitize the key concepts—not a complete transcription, but the material that deserves a permanent place in your knowledge system. Let your digital tools handle review materials: flashcards, searchable summaries, and cross-referenced notes that connect to other courses and future projects.

Which method for which subject?

| Subject type | Recommended method | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Lecture-heavy humanities | Cornell | Built-in review; handles factual recall |

| Conceptual/philosophical | Mind mapping | Shows non-linear connections |

| Hierarchical sciences | Outline | Captures classification and structure |

| Multi-topic surveys | Boxing | Prevents confusion between distinct topics |

| Problem-solving (math, physics) | Flow-based | Captures thinking process |

| Technical/terminology-heavy | Digital outline | Searchability for precise terms |

Subject-specific tips

For mathematics: Focus on worked examples, not just formulas. Write each step of the solution process. Add notes explaining why each step follows from the previous one. The outline and flow methods work well here.

For languages: Keep vocabulary in a separate notebook or digital flashcard system. During class notes, focus on grammar explanations, example sentences, and usage patterns—the conceptual material that's harder to flashcard.

For lab sciences: Create two parallel tracks: conceptual notes for lecture, procedural notes for lab. Boxing works well to separate these even on the same page.

How to review notes effectively

Taking great notes means nothing if you never review them. But most students review wrong—they re-read, highlight, and feel productive while learning almost nothing. Effective review means active recall: closing your notes and testing yourself.

The 24-hour rule

Your first review should happen within 24 hours of the lecture. This is when memories are fresh but starting to fade—the ideal moment to reinforce them. Spend 10–15 minutes reading through your notes once, then adding any details you remember but didn't capture in the moment. If you're using Cornell, this is when you fill in the cue column and write your summary. Most importantly, identify concepts you don't fully understand and flag them for deeper study—these gaps, caught early, are far easier to fill than the night before an exam.

Spaced repetition for notes

After the initial review, space your subsequent reviews for maximum retention. The spaced repetition schedule for notes follows a simple pattern: your initial review happens within the first 24 hours, then a quick review around day 3 focusing on items you flagged as unclear. By day 7, most material should feel solid, and a final review around day 14 locks it in for exams. This schedule isn't arbitrary—it's designed around the forgetting curve, intervening at the points where memories are about to slip away.

Review techniques by method

Each note-taking method has a natural review approach that maximizes its structure.

For Cornell notes, cover the right column and answer questions from your cues, checking accuracy and marking items that need additional review. The method was literally designed for this—if you're not doing this step, you're not really using Cornell.

For mind maps, redraw the entire map from memory on a blank page, then compare with your original to find gaps. The act of reconstruction, not just recognition, is what builds durable memory.

For outlines, convert your main headings into questions and answer them aloud. "Stages of mitosis" becomes "What are the stages of mitosis and what happens in each?" The hierarchy you created during note-taking becomes a hierarchy of comprehension questions.

For boxing, review one box at a time and explain each topic to yourself as if teaching a classmate. The visual separation that helped during capture now helps during review—you can focus on one chunk without interference from others.

For flow notes, trace your arrows and connections. Can you explain why each connection exists? If an arrow links two concepts and you can't articulate the relationship, that's a gap worth investigating.

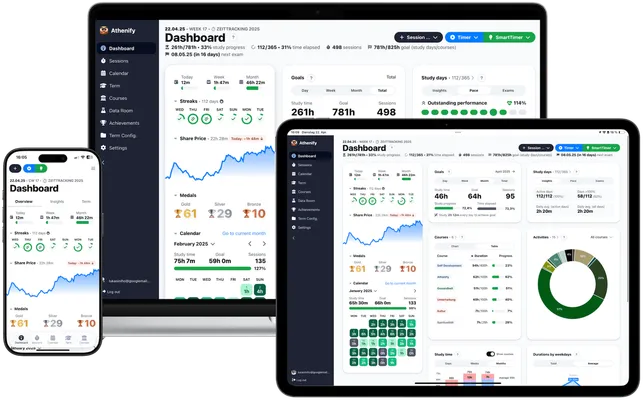

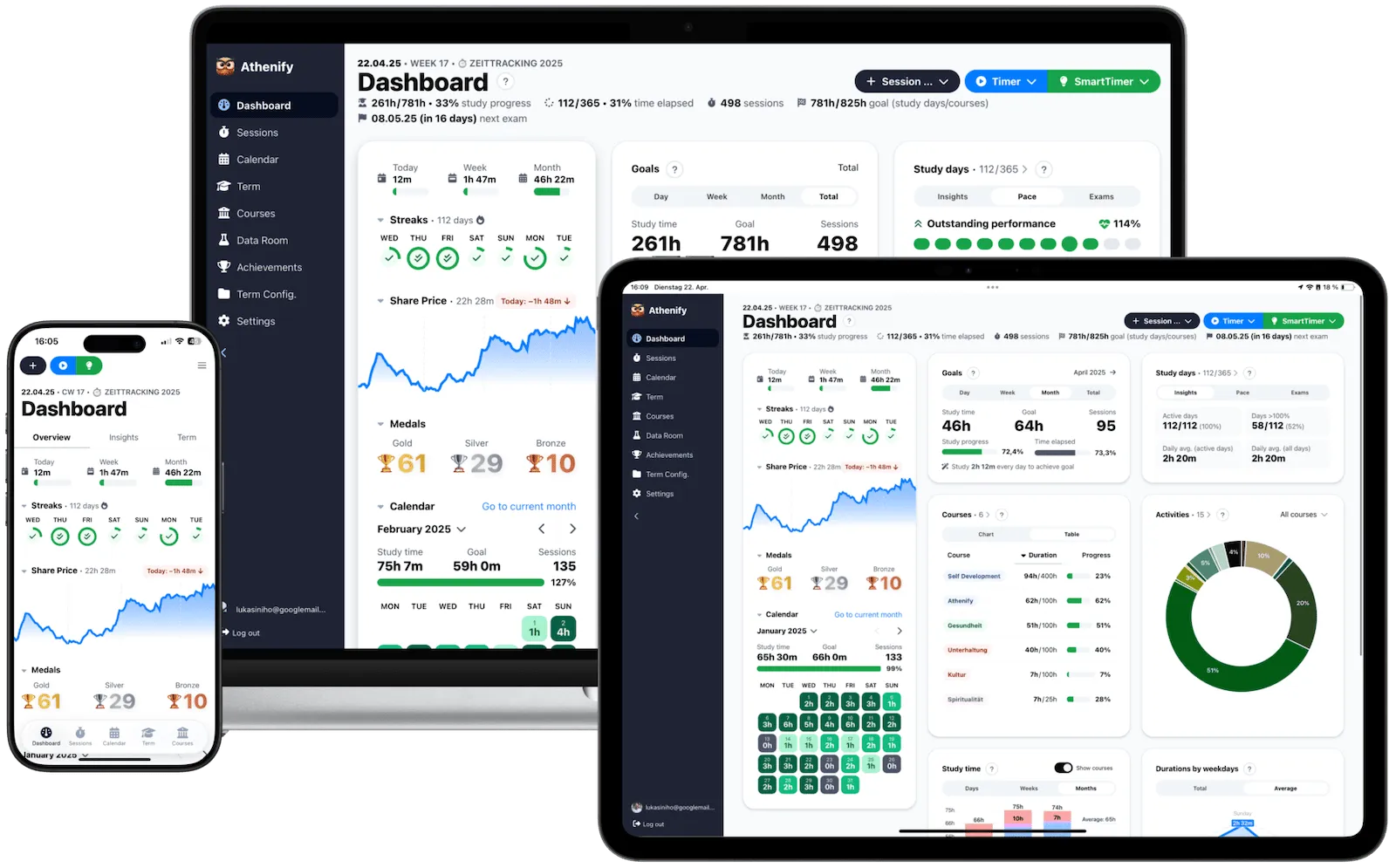

Try Athenify for free

Track your note-taking and review sessions. See which subjects get attention, build consistent study streaks, and know exactly where your time goes.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Building your note-taking system

The best note-taking method is the one you'll actually use—consistently, every class, every semester. Here's how to build a sustainable system:

Start with one method

Don't try to master all five methods at once. Pick one that fits your primary subject type and use it exclusively for two weeks. Once it feels natural, experiment with a second method for a different subject.

Create a capture-process-review cycle

Notes without review are just archives. Review without active recall is just re-reading. Build the full cycle.

The three-phase cycle is simple but rarely followed: Capture during lecture using your chosen method, focusing on understanding over transcription. Process within 24 hours by filling gaps, adding cues or questions, and digitizing if that's part of your system. Review using spaced repetition with active recall—not passive re-reading, but genuine testing of your memory. Each phase matters, and skipping any one of them dramatically reduces the value of the others.

Track your efforts

You can't improve what you don't measure. Track how much time you spend on notes and review. Are you actually doing those 24-hour reviews? Do some subjects get neglected? Time tracking reveals the gap between intention and reality—and helps you adjust before exams. Combine your note-taking practice with deep work sessions for maximum focus, and use the Pomodoro Technique to structure your review sessions.

Conclusion: notes as learning, not recording

The students who ace exams aren't the ones with the longest notes—they're the ones who process information as they write. Every note-taking method in this guide shares a common thread: they force you to think, not just transcribe.

Choose the method that matches your subject. Use handwriting for first-time learning, digital for long-term organization. Review within 24 hours, then space your reviews. Test yourself instead of re-reading. And remember: the goal isn't to record the lecture. It's to learn from it.

Your notes are only as good as what you do with them afterward. The Cornell cue column means nothing if you never cover the notes and quiz yourself. The mind map connections are useless if you never trace them during review. Pick a method, use it consistently, review actively—and watch your retention transform.