Here's a scene that plays out millions of times every day: a student sits down to study, opens their textbook, and reads. Highlights. Re-reads. Feels confident. Then bombs the exam. What went wrong? They fell for one of the most common traps in learning: confusing familiarity with knowledge. The material felt easy to process, so they assumed they'd learned it. But recognition isn't the same as recall—and on exam day, the difference becomes painfully clear.

The act of retrieving information strengthens your ability to retrieve it again.

This simple technique—tested extensively in cognitive science labs for over a century—may be the single most powerful tool you have for learning. It's one of the most effective study techniques backed by science. Here's everything you need to know to use it.

Why re-reading fails you

Before understanding why active recall works, let's understand why the alternative doesn't.

Re-reading feels productive. The material becomes familiar. You recognize concepts. You think: "I know this."

But recognition is not recall. On exam day, you won't be asked "Does this answer look familiar?" You'll be asked to produce information from memory—a completely different cognitive process.

"Students often prefer techniques that are easy and feel good over techniques that actually work. Re-reading falls into the first category; active recall falls into the second."

— Henry Roediger, Cognitive Psychologist

This is called the fluency illusion: when material feels easy to process, we assume we've learned it. But fluency and learning are not the same thing.

The passive learning trap

| Re-reading | Active Recall | |

|---|---|---|

| Direction | Page → eyes → short-term memory | Long-term memory → conscious awareness |

| Effort | Minimal—feels easy | High—feels hard (that's the point) |

| What happens | You recognize concepts | You retrieve and strengthen them |

| Result | Illusion of learning | Actual long-term retention |

The science behind active recall

Active recall works because of a phenomenon psychologists call the testing effect: the act of retrieving information from memory strengthens your ability to retrieve it again.

How memory actually works

When you learn something new, your brain creates a memory trace—a pattern of neural connections. But this trace is weak and temporary. Without reinforcement, it fades within days or weeks.

Here's the key insight: retrieving a memory is not a neutral act. Each time you successfully recall information, you strengthen the neural pathway.

What happens during active recall:

- You attempt to retrieve information from memory

- The retrieval effort strengthens neural pathways

- The memory becomes more durable and accessible

- Each successful recall extends how long you'll remember

Think of it like a path through a forest—the more you walk it, the clearer and easier to navigate it becomes. Re-reading, by contrast, is like flying over the forest in a helicopter: you recognize the landscape below, but you haven't actually walked the path, so you couldn't navigate it on foot.

Re-reading doesn't trigger this strengthening because you're not retrieving—you're recognizing. The information is right there on the page, doing the cognitive work for you.

Research evidence

The evidence for active recall is overwhelming. In their landmark 2008 study, Karpicke and Roediger found that students who tested themselves remembered 80% of material a week later, compared to just 36% for those who only studied passively—more than double the retention. Even more striking, a 2006 study by Roediger and Karpicke demonstrated that a single test produced greater long-term retention than three additional study sessions. One retrieval practice session beat three passive reviews.

The effects extend beyond the laboratory. McDaniel and colleagues followed students through an actual college course in 2007 and found that those using active recall techniques earned a full letter grade higher than their peers using traditional study methods. This isn't a marginal improvement—it's the difference between a B and an A, or between passing and failing.

Testing isn't just a way to assess learning—it's a way to cause learning.

How to practice active recall

1. The "close the book" test

After reading a section—a paragraph, a page, a chapter—close the book and ask yourself: "What did I just learn?" Write down everything you can remember without peeking. Then, and only then, open the book and check what you missed. This simple exercise takes thirty seconds but transforms passive reading into active learning.

This is the simplest form of active recall. No tools required, no apps to download, no special materials to buy. Just you, the material, and the uncomfortable-but-productive act of trying to remember. The gaps you discover—the things you thought you knew but couldn't produce—become your study priorities.

2. Flashcards done right

Flashcards are a classic active recall tool, but most students use them wrong. They flip to the answer too quickly, glance at it, think "Oh yeah, I knew that," and move on. But recognizing an answer isn't the same as recalling it—and that shortcut defeats the entire purpose.

The key is discomfort. When you see a flashcard prompt, sit with it. Wait at least five to ten seconds before flipping, and actually verbalize or write your answer first. If you couldn't produce the answer from memory, be honest with yourself: you didn't know it. That failed retrieval attempt is valuable—it shows you exactly what needs more work.

Focus your time on the cards you struggle with, not the ones you've already mastered. Digital flashcard apps like Anki and Quizlet use SRSSpaced Repetition System algorithms to automate this prioritization—showing you cards at optimal intervals based on your performance. But physical cards work too, as long as you're honest about what you actually know. For a structured approach to creating flashcards from class material, see our guide on how to take effective lecture notes.

3. Practice problems before solutions

For problem-based subjects—math, physics, programming, economics—there's a counterintuitive approach that works remarkably well: try problems before looking at worked examples.

Even if you fail—especially if you fail—the struggle primes your brain to understand the solution more deeply when you do see it. You've already identified what you don't know, so when the explanation arrives, it fills a gap you're aware of rather than washing over you like background noise.

Start by reading the problem carefully. Then attempt a solution, even a partial one—sketch out what you think the first step might be, identify where you get stuck, notice which concepts you're uncertain about. Only then should you study the worked solution, paying special attention to the parts where you struggled. Afterward, try a similar problem immediately to cement what you've learned.

4. Teach it to learn it (the Feynman Technique)

Explaining a concept out loud—as if teaching someone else—is powerful active recall.

"If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough."

— Often attributed to Einstein

When you teach, you're forced to retrieve information, organize it logically, and identify gaps in your understanding. If you stumble or can't explain something clearly, you've found exactly what you need to study more.

You don't need an actual audience. Explain concepts to a study partner if you have one, but you can also record yourself on your phone, write out explanations longhand, or simply talk through material out loud in an empty room. Some students find it helpful to pretend they're explaining the concept to a curious twelve-year-old—if you can make it simple enough for a child to understand, you truly know it.

5. Self-quizzing

Create questions based on your material, then answer them without looking. The quality of your questions matters—they should force genuine recall, not just recognition.

Good questions ask for explanations, not yes/no answers: "What is photosynthesis and why does it matter?" rather than "Is photosynthesis important?" Ask how processes work, what the differences are between related concepts, why phenomena occur, and for specific examples of principles in action. These open-ended formats require you to construct knowledge from memory rather than simply confirming what you already suspect.

| ❌ Weak questions (recognition) | ✅ Strong questions (recall) |

|---|---|

| Is the mitochondria the powerhouse of the cell? | What is the function of mitochondria? |

| Did the French Revolution begin in 1789? | When and why did the French Revolution begin? |

| Is Python an interpreted language? | Explain how Python executes code differently than C. |

6. Past exams and practice tests

Taking full practice tests under exam-like conditions is active recall at scale. This makes it essential for effective exam preparation.

Combining active recall with other techniques

Active recall becomes even more powerful when combined with complementary strategies.

Active recall + spaced repetition

The best time to practice recall is right before you're about to forget.

Spacing your recall attempts over increasing intervals prevents forgetting and builds long-term retention. The idea is simple: instead of reviewing everything in one marathon session, you spread your recall practice over time—reviewing new material the next day, slightly older material in three days, older material in a week, and well-established material every few weeks.

This spacing exploits how memory works. Each time you successfully recall something just as you're about to forget it, you strengthen that memory trace more than if you'd reviewed it while it was still fresh. Apps like Anki automate this scheduling algorithmically, but you can also space your own review sessions manually with a simple calendar system. For a deep dive into this technique, see our complete guide to Spaced Repetition.

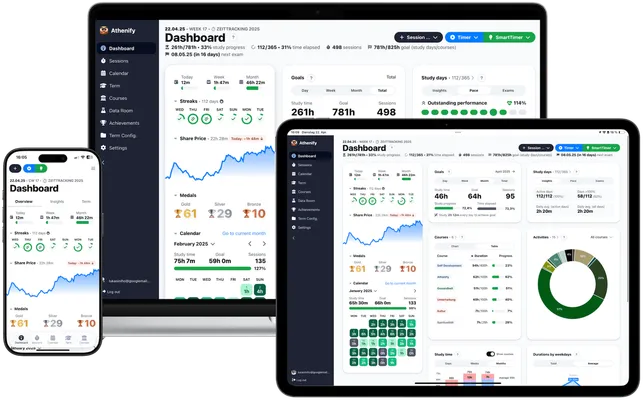

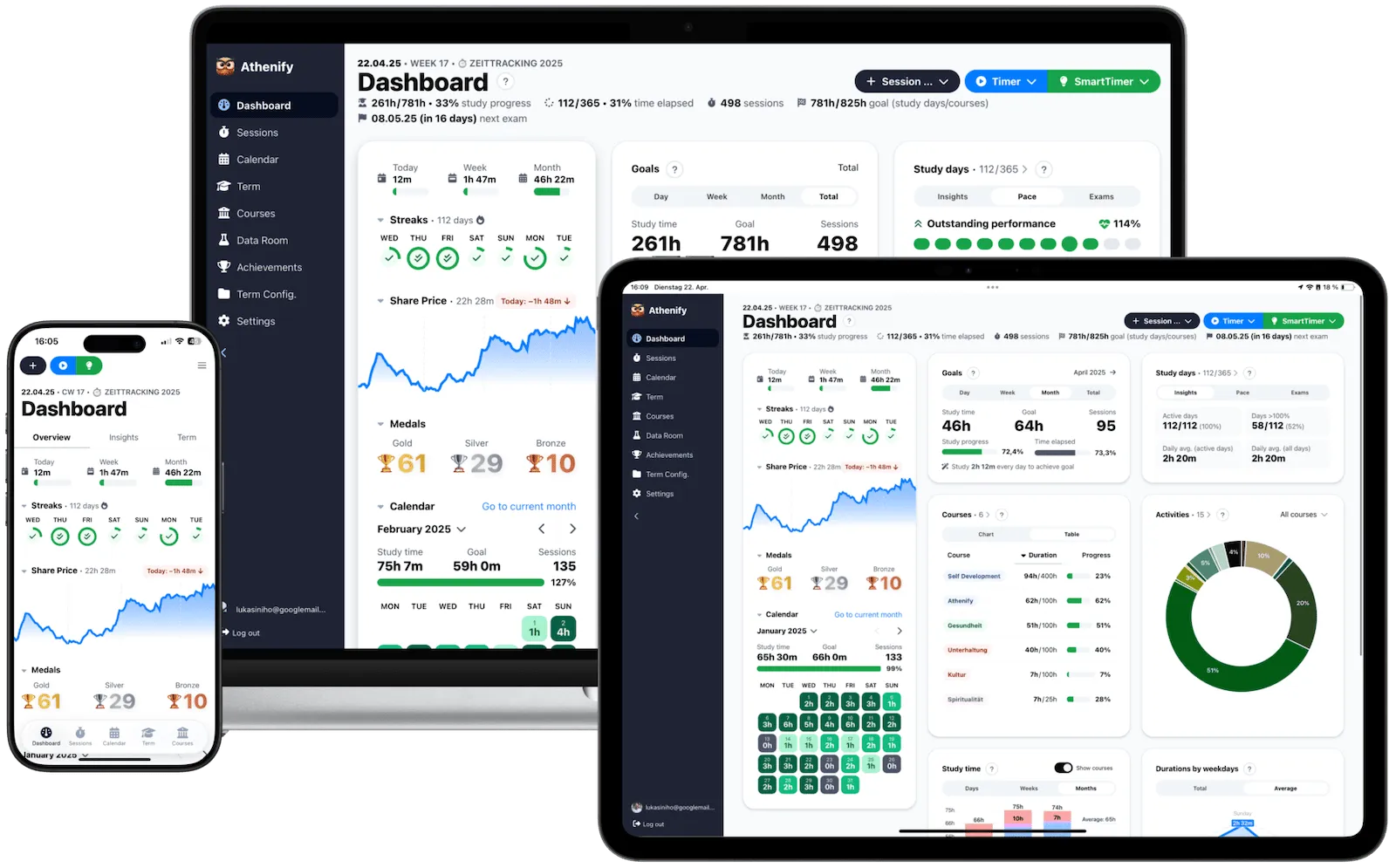

Active recall + time tracking

Tracking your study time keeps you accountable and ensures you're actually engaging with the material—not just staring at pages.

When you log study sessions with Athenify, you build a record of your effort. You can see patterns: which subjects get neglected, when you study most effectively, how consistency affects your results.

Try Athenify for free

Track your active recall sessions, build consistency with streaks, and see which subjects need more attention.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

What gets tracked gets done. What gets done gets learned.

Active recall + interleaving

Instead of studying one topic until you've "mastered" it (blocked practice), mix different topics within a single study session (interleaved practice).

This feels harder—and that's the point. Interleaving forces your brain to repeatedly retrieve different types of information, strengthening each one. Consider combining active recall with deep work sessions for maximum learning efficiency, and use the Pomodoro Technique to structure your practice sessions.

How much active recall is enough?

As a general rule: spend at least 50% of your study time testing yourself. If you're studying for an hour, use roughly half that time reading, taking notes, and understanding new material—and the other half with your notes closed, actively practicing recall.

For review sessions covering material you've already learned, you can push this ratio even higher—70 to 80 percent recall, with only brief reference checks to fill gaps.

Quality indicators

How do you know if you're doing active recall correctly? Pay attention to how it feels. Effective active recall is uncomfortable—studying should feel more effortful than just reading, and you should frequently be surprised by what you can't remember. If your recall improves noticeably across sessions and you perform better on practice tests than expected, you're on the right track.

Conversely, if you're flipping flashcards instantly without thinking, rarely encountering material you don't know, or finding that studying feels easy and comfortable, something is wrong. Easy studying usually means ineffective studying. And if practice tests still catch you off guard despite hours of "review," you've probably been re-reading instead of recalling.

Common objections (and why they're wrong)

Students often resist active recall, and the objections tend to follow predictable patterns. "It takes too long," they say—but active recall actually saves time. Students who use it need fewer total study hours to achieve the same results. Re-reading five times is less effective than reading once and recalling twice. You're trading inefficient hours for effective minutes.

"It's too hard," comes the next complaint. Yes—that's the point. The effort of retrieval is what builds memory. If studying feels easy and comfortable, you're probably not learning much. The discomfort is the learning happening.

"I need to understand first, then I'll test myself," students insist. But understanding and recall aren't separate stages—they reinforce each other. Attempting to recall material (even unsuccessfully) improves subsequent understanding by highlighting what you don't know. Don't wait until you feel "ready." You'll be waiting forever.

Finally, there's the subject-specific excuse: "It doesn't work for my field." But active recall works for every subject: sciences, humanities, languages, professional exams. The specific techniques may vary—flashcards for vocabulary, practice problems for math, case analysis for law—but the underlying principle is universal.

Conclusion: Make active recall your default

Every time you read instead of recall, you're choosing the easy path over the effective one.

Active recall isn't just another study tip—it's the foundation of effective learning. The shift is simple but profound: after every reading session, close your materials and write down what you remember before moving on. Create flashcards for key concepts and test yourself honestly, without peeking. When facing problem sets, attempt solutions before looking at worked examples. Explain concepts out loud as if teaching someone who's never heard of the topic.

The students who master active recall don't just perform better on exams—they remember material for years, not weeks. They learn faster and forget slower. And perhaps most importantly, they spend less total time studying, because their study time actually works. The irony is that the technique that feels hardest in the moment is the one that makes everything easier in the end.