You walk out of a 50-minute lecture with four pages of dense, continuous text. Every word the professor said is there--or close to it. You feel accomplished. You did the work. You showed up and wrote it all down.

Three weeks later, you open those notes to study for the midterm and realize you have no idea what any of it means. The sentences run together. You can't tell what was important and what was a tangent. The examples make no sense without the professor's explanation. Your diligent transcription has produced a document that's useless for the one thing you actually need it for: learning.

This is the trap most students fall into. They confuse capturing information with processing it. They treat note-taking as a recording task when it should be a thinking task. The difference between students who struggle before exams and students who breeze through them often comes down to this single distinction: are you transcribing, or are you learning while you write?

The goal of lecture notes isn't to create a transcript. It's to create a tool for thinking.

Why most lecture notes fail

Before fixing your note-taking, it helps to understand exactly why the default approach--write everything down as fast as you can--produces such poor results.

The transcription trap

When you try to capture every word, you shift into what researchers call "non-generative" note-taking. Your brain operates as a relay station: information enters through your ears and exits through your pen or keyboard without being processed in between. You are functioning as a human audio recorder, and a less reliable one at that.

Generative note-taking, by contrast, requires you to select, paraphrase, organize, and connect. These cognitive processes create understanding. When you write "Photosynthesis converts light energy into chemical energy stored in glucose," you are just copying. When you write "Plants use sunlight to make food (glucose)--opposite of cellular respiration," you are thinking. Same information. Vastly different learning outcomes.

The illusion of completeness

Long, detailed notes feel productive. They look impressive. They create the comfortable illusion that you "have everything." But completeness in notes often correlates inversely with comprehension. The students with the longest notes are frequently the ones who understand the least--because they spent their cognitive resources on capture rather than processing.

No review pathway

The final failure mode: notes that contain no built-in mechanism for review. A wall of continuous text gives you nothing to grab onto. You can re-read it (passive, ineffective) or you can try to figure out what to study (overwhelming). Effective notes include questions, summaries, or structural cues that tell you how to review them. Without these, notes are archives--not study tools.

The three-phase system for effective lecture notes

Effective note-taking is not a single activity. It is a three-phase process: capture during class, process within 24 hours, and review at spaced intervals. Each phase has a distinct purpose, and skipping any one of them dramatically reduces the value of the others.

Phase 1: Capture -- what to do during the lecture

Your only job during lecture is to capture the important information in a format you can work with later. This means being selective, organized, and fast--but not exhaustive.

What to write down

Focus your capture on five categories of information:

Main concepts and arguments. When the professor introduces a new idea, defines a term, or presents a thesis, write it down. These are the structural elements of the lecture--the ideas everything else supports.

Key examples and evidence. Don't copy examples verbatim. Instead, note what the example illustrates: "Pavlov's dog experiment --> classical conditioning = involuntary response to neutral stimulus after pairing." The principle matters more than the details.

Connections to other material. When the professor links the current topic to a previous lecture, a textbook chapter, or another discipline, capture that connection. These are often the most valuable parts of a lecture and the easiest to miss.

Formulas, dates, and precise facts. Anything specific that you cannot reconstruct from memory deserves space in your notes. You can reason your way to a concept, but you cannot reason your way to a date or a constant.

Your own confusion. This is the one most students skip. When something doesn't make sense, mark it with a question mark or write "???" in the margin. These markers tell you exactly what to investigate during your processing phase.

What to leave out

Anything on the slides. If the professor posts slides, don't copy them. Write what the professor says about the slides--the explanations, context, and nuances that won't be in the PDF.

Anecdotes and tangents. Entertaining stories are memorable but rarely tested. Unless the anecdote illustrates a core concept, skip it.

Verbatim quotes. Unless the exact wording matters (a legal definition, a literary passage), paraphrase. The act of paraphrasing is the act of processing.

Leaving space

This is a small habit with outsized impact. Leave blank lines between topic sections. Skip lines when the lecture shifts direction. Leave wide margins. This space serves two purposes: it visually separates topics during review, and it gives you room to add information during processing.

Students who cram every inch of the page with text create notes that are dense, intimidating, and difficult to revisit. White space is not wasted space--it is review space.

Choosing a method

Different lectures demand different methods. For a complete overview, see our guide to note-taking methods. Here is a quick decision framework:

| Lecture type | Recommended method | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Linear, content-heavy | Cornell Method | Built-in cue column creates review structure |

| Hierarchical, fast-paced | Outline method | Fastest for structured content |

| Conceptual, discussion-based | Mind mapping | Captures non-linear connections |

| Multi-topic | Boxing method | Visually separates distinct topics |

| Problem-solving | Flow-based | Captures thinking processes |

Phase 2: Process -- what to do within 24 hours

Phase 2 is where most students fail. Not because it is hard, but because it feels optional. It isn't. Processing your notes within 24 hours is the single most impactful study habit you can build.

Why 24 hours?

The forgetting curve, first described by Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885 and confirmed in countless subsequent studies, shows that memory decay is steepest in the first 24 hours after learning. You forget more between today and tomorrow than between tomorrow and next week. Reviewing while the material is fresh catches this decay at its steepest point.

The processing routine (10-15 minutes per lecture)

1. Read through your notes once. Not to memorize--just to re-enter the lecture mentally. Notice any gaps, confusing sections, or question marks you left.

2. Fill gaps. Use the textbook, lecture slides, or a classmate's notes to complete any sections where you fell behind or didn't understand. This is detective work, not transcription--fill only what you need.

3. Add questions and cues. If you use the Cornell Method, fill in the cue column with questions that test the material. If you use another method, write 3-5 questions in the margin that you should be able to answer from these notes.

4. Write a summary. In 2-3 sentences, capture the main takeaway from the lecture. Force yourself to distill: "If I could only remember one thing from this lecture, what would it be?" This summary becomes your entry point during exam review.

5. Flag what you don't understand. After processing, you should have a clear picture of what you know and what you don't. The things you don't understand need additional work--office hours, study groups, textbook deep-dives. Identifying these gaps early is infinitely better than discovering them the night before the exam.

The digital processing option

If you take handwritten notes during lectures, the processing phase is an ideal time to digitize key concepts. Don't transcribe everything--extract the important ideas and add them to your digital knowledge system. This selective digitization forces you to evaluate what matters while simultaneously reviewing the material.

For students building a Zettelkasten or a second brain, the processing phase is when lecture notes become permanent knowledge notes. Each important idea gets written as an atomic note in your own words and linked to related concepts across all your courses.

Phase 3: Review -- what to do at spaced intervals

Taking and processing notes is worthless if you never review them. But most students review wrong--they re-read, highlight, and feel a comforting sense of familiarity that is not the same as actual learning.

Active recall, not passive re-reading

Effective review means closing your notes and testing yourself. Cover the notes column and answer your cue questions. Look at section headings and try to recall what's underneath. Explain the main ideas aloud as if teaching a classmate. This is active recall--the most powerful study technique available.

If you can't explain it without looking at your notes, you don't know it yet.

The spaced review schedule

Don't cram all your review into the night before the exam. Space it out to align with the forgetting curve:

- Day 1 (your processing session): First review. Fill gaps, add questions, write summary.

- Day 3: Quick recall test. Cover notes, answer cue questions. Note what you missed.

- Day 7: Full review. By now, most material should feel solid. Focus on persistent gaps.

- Day 14: Final consolidation. Material should be in long-term memory.

This spaced repetition schedule means you review each lecture only four times, for a total of perhaps 30-40 minutes spread over two weeks. Compare that to the three-hour cramming session the night before the exam--less total time, dramatically better results.

Adapting to different lecture formats

The slide-heavy lecture

Many professors rely heavily on slides, which creates a temptation: why take notes when the slides are posted online? Because slides contain information, not understanding. Your notes should capture what the professor says about the slides--context, explanations, emphasis, connections.

A practical approach: print or download the slides before class (if available). During the lecture, annotate the slides with the professor's verbal commentary. Focus on the "why" behind each slide, not the "what" that's already printed.

The discussion-based seminar

Seminars are harder to take notes on because ideas emerge non-linearly from multiple speakers. Don't try to capture everything. Focus on:

- The main question or thesis being discussed

- The strongest arguments on each side

- Moments of consensus or unresolved disagreement

- Your own reactions and questions

Mind mapping works well here--central question in the middle, different arguments branching outward, cross-connections between related points.

The problem-solving lecture

In math, physics, and computer science, lectures often consist of worked examples. For these, the process is as important as the answer. Note each step of the solution and why that step follows from the previous one. "Integrate both sides" is a step. "Integrate both sides because the variables are now separated" is understanding.

Leave space after each example to write a brief note about when this method applies: "Use separation of variables when the equation can be written as f(x)dx = g(y)dy." These application notes become invaluable during exam preparation.

The fast-talking professor

Some professors speak at a pace that makes selective note-taking impossible. Strategies:

- Use the outline method for maximum speed

- Abbreviate aggressively -- even more than usual

- Record the lecture (with permission) as a backup, but still take active notes

- Leave gaps and fill them immediately after class using slides or the recording

- Focus on structure: capture the main points and topic transitions, even if you miss details

The pre-lecture preparation that multiplies everything

One habit separates students who take great notes from students who struggle: pre-reading. Even 10-15 minutes of previewing the material before lecture transforms your note-taking from reactive to proactive.

When you know what's coming, you can:

- Identify the main concepts in advance and listen for them

- Focus your notes on what's confusing rather than what's obvious

- Recognize connections to previous material in real time

- Ask better questions during the lecture

You don't need to study the material deeply. Skim the textbook chapter headings, read the introduction and conclusion, and review the learning objectives if they're listed. This creates a mental framework that lecture content slots into naturally.

Pre-reading for 10 minutes before lecture is worth more than re-reading for an hour after.

Building the habit

Knowing how to take good notes is useless if you don't actually do it. Here is a minimal, sustainable routine that incorporates all three phases.

Before each lecture (5-10 minutes)

- Preview the topic in the textbook or syllabus

- Set up your page (draw Cornell lines, prepare a fresh mind map, etc.)

- Review your notes from the previous lecture for 2 minutes to prime your memory

During the lecture (the full session)

- Capture selectively using your chosen method

- Use abbreviations, leave space, mark confusion

- Don't worry about perfection--you'll process later

After the lecture, same day (10-15 minutes)

- Read through notes once

- Fill gaps from slides, textbook, or classmates

- Add questions, cues, and a summary

- Flag topics you don't understand

At spaced intervals (5-10 minutes per session)

- Day 1: initial processing (above)

- Day 3: quick recall test

- Day 7: full review

- Day 14: final consolidation

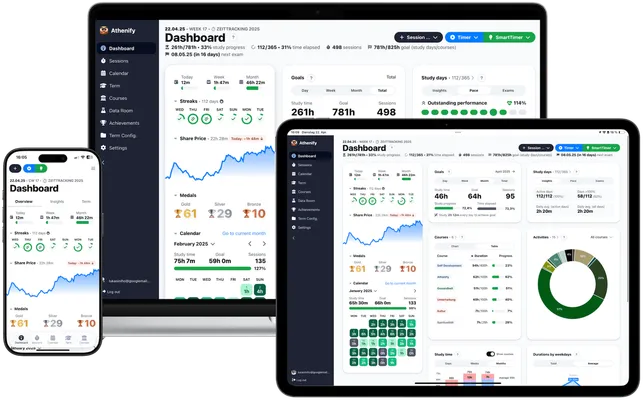

Total extra time per lecture: approximately 30-40 minutes spread over two weeks. This is less than most students spend cramming the night before an exam--and it produces vastly better results. Track your sessions alongside your other study habits to build accountability and see where your time actually goes.

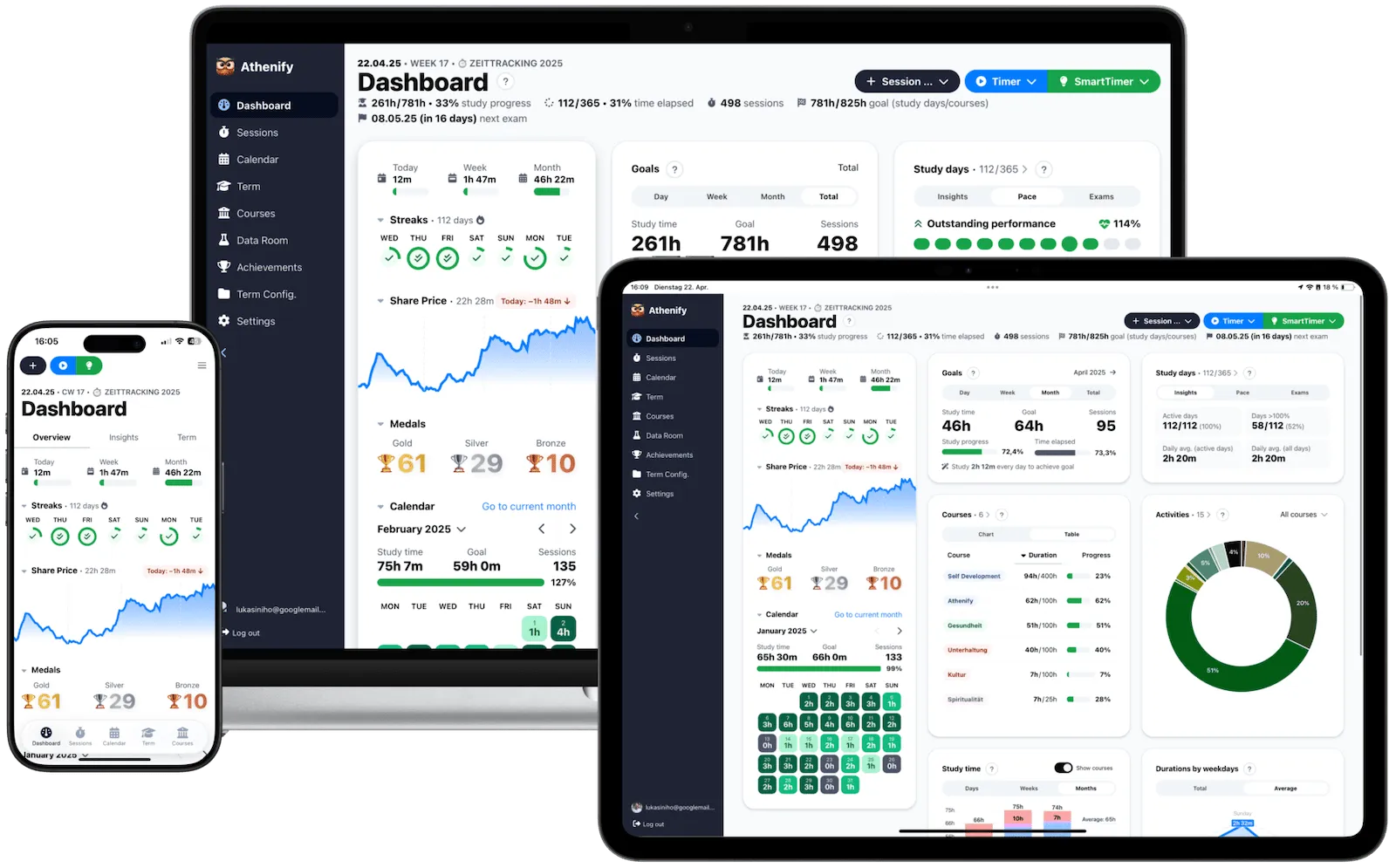

Try Athenify for free

Track your lecture note sessions and review habits. Build streaks, see patterns, and know exactly where your study time goes.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Conclusion

Taking effective lecture notes is not about writing more. It is about thinking more while you write. The students who succeed are not the fastest writers or the most diligent transcribers--they are the ones who treat note-taking as an active learning process with three distinct phases: selective capture, deliberate processing, and spaced active review.

Choose a note-taking method that fits your subject. Use abbreviations and leave space. Process within 24 hours--not by rewriting, but by adding questions, filling gaps, and summarizing. Then review using active recall at spaced intervals.

The notes you take tomorrow don't have to look like the notes you took yesterday. Every lecture is a chance to write less, think more, and learn better.