You are staring at 40 pages of linear notes from the past month of your philosophy course. Somewhere in those pages are the connections between Kant's categorical imperative, Hume's empiricism, and the professor's argument about how they relate to modern ethics. But the notes are organized by date, not by idea. The connections you need to see are scattered across weeks of chronological entries, invisible to any quick review.

Now imagine the same material arranged on a single page. Kant in one branch, Hume in another, modern ethics in a third--with lines drawn between the ideas that connect them, color-coded by theme, the entire conceptual landscape visible at a glance. That is a mind map. And for subjects where understanding relationships matters more than memorizing isolated facts, it is one of the most powerful study tools available.

Mind mapping is not a gimmick. It is a structured visual technique backed by cognitive science research, used by students, professionals, and researchers worldwide. This guide covers how to create effective mind maps, when they outperform linear notes, and how to use them for exam preparation, essay planning, and long-term knowledge building.

Linear notes show you what you learned. Mind maps show you how it all fits together.

What is mind mapping?

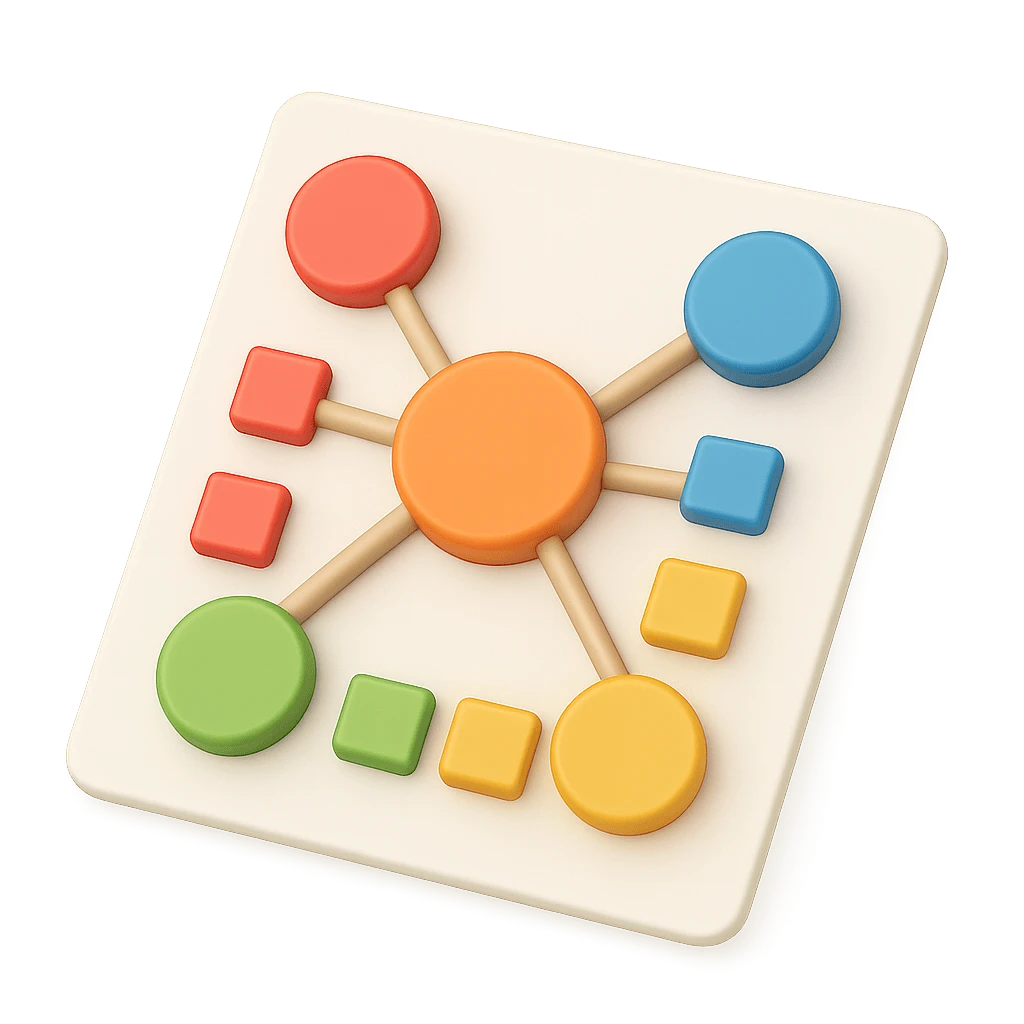

Mind mapping is a visual note-taking and thinking technique where information radiates outward from a central topic. Instead of writing top-to-bottom in lines, you build a branching diagram that shows relationships between ideas.

The basic structure

1. Central topic. Write the main subject in the center of a blank page (landscape orientation works better than portrait). Circle it or make it bold.

2. Main branches. Draw thick lines outward from the center for each major sub-topic or theme. Label each branch with a keyword or short phrase. Use different colors for different branches.

3. Sub-branches. From each main branch, draw thinner lines for supporting details, examples, and evidence. Continue branching as deep as needed.

4. Cross-connections. Draw dotted lines or arrows between branches that relate to each other--even if they're on opposite sides of the map. These cross-connections are where the real insight happens.

5. Visual elements. Add simple icons, symbols, or small drawings wherever they help. A question mark for unresolved issues. A star for key exam material. A light bulb for your own insights.

The science behind mind mapping

Mind mapping is not just a pretty way to organize notes. Several cognitive principles explain why it works.

Dual coding theory

Allan Paivio's dual coding theory proposes that information encoded both verbally (words) and visually (images, spatial layout) creates two memory pathways instead of one. Mind maps inherently use both: the text on each branch is verbal encoding, while the spatial arrangement, colors, and connections provide visual encoding.

Elaborative processing

Creating a mind map forces you to make decisions that linear note-taking does not: Where does this concept belong? What does it connect to? Is it a main branch or a sub-branch? Each decision requires processing the information at a deeper level than simply writing it down in sequence.

Spatial memory

Humans have remarkably strong spatial memory--you can probably recall the layout of your childhood home in detail. Mind maps leverage this by giving information a physical location on the page. During an exam, you can often recall that a concept was "on the upper right branch, connected to the branch about empiricism." This spatial cue triggers recall of the content itself.

<info-box type="info" title="A note on "learning styles""> You may have heard that mind mapping is only for "visual learners." The learning styles theory--the idea that students are categorically visual, auditory, or kinesthetic learners--has been largely debunked by research. Mind mapping works not because some people are "visual" but because visual-spatial processing strengthens memory for everyone. That said, people differ in their comfort with visual techniques, and mind mapping does require practice to become fluent.

Chunking

A mind map naturally chunks information into groups (branches) with clear hierarchical relationships. Cognitive research shows that chunked information is easier to remember than a flat list--your working memory can hold 4-7 chunks, and each chunk can contain multiple related items.

When to use mind maps (and when not to)

Mind mapping is powerful but not universal. Knowing when to deploy it--and when to choose a different note-taking method--is what separates strategic students from those who force one technique into every situation.

Mind maps excel at

Synthesizing material after lectures. You sat through the lecture and took linear notes. Now, during your review session, create a mind map that connects the key ideas. This synthesis forces you to identify relationships that weren't obvious during the lecture.

Planning essays and papers. Before writing, map out your argument: thesis in the center, supporting arguments on main branches, evidence and examples on sub-branches, counterarguments on their own branch. The visual overview prevents the structural problems (wandering arguments, missing evidence, disconnected sections) that plague unplanned essays.

Exam review for conceptual subjects. Mind maps compress an entire topic onto one page. Before an exam, create a mind map for each major topic area. Use it to see the big picture, then zoom into weak areas for deeper study.

Connecting ideas across courses. Mind maps don't care about course boundaries. A map on "How humans make decisions" might draw from your psychology, economics, philosophy, and neuroscience courses. These cross-course connections are often the most valuable learning moments in a student's career.

Brainstorming and ideation. When you need to generate ideas--for a thesis topic, a project, or a creative assignment--mind mapping's radial structure encourages expansive thinking in ways that linear lists do not.

Mind maps struggle with

Fast-paced lectures. Creating a mind map in real time during a rapid lecture is extremely difficult. By the time you've decided where to place a concept and what it connects to, the professor has moved on. For lecture capture, use a faster method like Cornell notes or outlining, then mind map during review.

Sequential or procedural content. Step-by-step processes, mathematical proofs, and chronological narratives are inherently linear. Forcing them into a radial format adds complexity without adding clarity.

Precise, detail-heavy material. Mind maps trade detail for overview. If you need to remember exact dates, formulas, or definitions, a mind map's keyword-based branches may sacrifice too much specificity. Supplement with detailed notes or flashcards.

Mind maps are for understanding. Linear notes are for capturing. Use both--at the right time.

How to create an effective study mind map

Step 1: Start with the right materials

For hand-drawn maps: Use blank, unlined paper in landscape orientation--A3 is ideal, A4 works fine. Have at least 4-6 colored pens or markers. Unlined paper is important: lines encourage linear thinking, which is exactly what you are trying to avoid.

For digital maps: Tools like Miro, MindMeister, Xmind, or even Apple Freeform provide unlimited canvas space and easy reorganization. Digital is better for maps you will update over time. Hand-drawn is better for initial creation and memory encoding.

Step 2: Define your central topic

Write the topic in the center and circle it. Be specific: "Causes of World War I" is better than "History." "Pavlov's Classical Conditioning" is better than "Psychology Chapter 6." The more focused the center, the more useful the map.

Step 3: Identify main branches (before you start drawing)

Pause before drawing. Think about the 4-7 major sub-topics or themes. Write them on a scrap of paper first if needed. This prevents the common mistake of starting with one branch, over-developing it, and running out of space for the others.

Step 4: Build branches with keywords, not sentences

Write single keywords or very short phrases on each branch--never full sentences. "Encoding specificity" not "The encoding specificity principle states that memory retrieval is most effective when the conditions at retrieval match the conditions at encoding." The keyword triggers your memory of the full concept. If it doesn't, that's a signal you need to study that concept more deeply.

Step 5: Use color deliberately

Assign one color per main branch and use it consistently through all sub-branches. This creates visual grouping that aids recall. Some students also use a color system for types of information: blue for facts, green for examples, red for questions or disagreements.

Step 6: Draw cross-connections

This is the most important step and the one most students skip. After completing your branches, look for relationships between ideas on different branches. Draw dotted lines or arrows and label the connection: "contradicts," "supports," "caused by," "similar to." These cross-connections are the insights that transform a simple diagram into a genuine thinking tool.

Step 7: Review and refine

Step back and look at your map as a whole. Does the spatial arrangement make sense? Are related branches near each other? Is there a branch that feels disconnected--maybe it belongs on a different map? Adjust while the material is fresh.

Mind mapping for exam review

Mind maps are exceptionally powerful for exam preparation. Here is a concrete workflow.

The overview map

One week before the exam, create one master mind map for the entire course or exam scope. Each main branch represents a major topic area. Sub-branches cover key concepts within each area. This map should fit on a single large page--it is your executive summary of the entire course.

The detail maps

For each main branch that needs deeper review, create a separate, detailed mind map. These drill into specific topics with more sub-branches, examples, and connections.

The recall test

This is where mind maps become an active study tool rather than a passive reference. Take a blank page and try to redraw your overview map from memory. Don't peek. Draw everything you can remember: branches, sub-branches, connections, keywords.

Then compare your recall map with the original. Every missing branch, every forgotten connection, every misplaced sub-topic tells you exactly what you need to study. This is active recall in visual form--and it is far more diagnostic than re-reading notes or highlighting a textbook.

Mind maps as cheat sheet substitutes

Some professors allow a one-page reference sheet during exams. Mind maps are perfect for this--they compress maximum information into minimum space while maintaining visual organization. Even if the exam is closed-book, creating the reference sheet mind map is an excellent study exercise. The act of deciding what goes on the sheet forces you to evaluate importance and prioritize.

Mind mapping for essay writing

Mind maps solve the most common structural problems in student essays: wandering arguments, missing evidence, and disconnected sections.

The essay planning workflow

1. Central thesis. Write your argument in the center.

2. Supporting arguments. Create main branches for each supporting point, in the order you plan to present them.

3. Evidence. Add sub-branches with specific evidence, examples, quotes, and citations for each argument.

4. Counterarguments. Give counterarguments their own branch. Then draw connections showing where your supporting arguments address them.

5. Connections. Look for connections between branches. If Argument 2 builds on Argument 1, draw that link. If your conclusion synthesizes elements from multiple branches, show those connections.

6. Write. Now you are not writing from scratch--you are expanding each branch into prose, following a visual outline that shows both the sequence and the connections.

This approach is particularly useful for academic writing where structural clarity directly affects your grade. A mind-mapped essay plan prevents the meandering that happens when you start writing without a clear map of where the argument is going.

Combining mind maps with other methods

Mind mapping works best as part of a system, not as the only technique you use.

Mind maps + Cornell notes

Use Cornell notes during lectures for structured capture. During your processing phase, create a mind map that synthesizes the lecture's key ideas and connections. The Cornell notes provide the detail; the mind map provides the overview. Together, they cover both the trees and the forest.

Mind maps + Zettelkasten

If you maintain a Zettelkasten, mind maps serve as visual structure notes. When a cluster of permanent notes has grown large enough, create a mind map that shows how they connect. Store the map alongside the structure note in your system. This gives you both a visual and a textual entry point into the topic.

Mind maps + flashcards

For each branch or cross-connection on a mind map, create a flashcard that tests the relationship. "How does encoding specificity relate to context-dependent memory?" The mind map provides the big picture; the flashcards drill the specific connections. Review both using spaced repetition for maximum retention.

Mind maps + digital notes

Take digital or handwritten notes during lectures for speed, then create hand-drawn mind maps during review for deeper processing. The act of translating linear notes into a spatial format requires you to think about relationships you might not have noticed in the original notes.

Common mind mapping mistakes

Mistake 1: Too much text

Mind maps use keywords, not sentences. If your branches contain full sentences, you are writing linear notes in a radial format--gaining the overhead of mind mapping without the benefits. Force yourself to use single words or very short phrases.

Mistake 2: No cross-connections

A mind map without cross-connections is just a hierarchical outline drawn in a circle. The cross-connections between branches are where genuine insight lives. If your map has zero cross-connections, you are not thinking relationally yet.

Mistake 3: Trying to mind map during fast lectures

Real-time mind mapping during a lecture is a recipe for frustration. The professor talks faster than you can decide spatial placement. Use mind maps during review, not during capture. For lecture capture, faster linear methods work better.

Mistake 4: Making it too big

A mind map that spans multiple pages loses its primary advantage: the one-page overview. If your map is growing too large, create sub-maps for detailed branches and keep the master map at a summary level.

Mistake 5: Never reviewing the map

A mind map you create and never look at again is no better than the linear notes you were replacing. Use the recall test method described above: redraw from memory, compare, and study the gaps. The map's value is realized through active review, not through creation alone.

Getting started: your first study mind map

You don't need special training or tools to begin. Here is a five-minute exercise.

- Pick one topic from a recent lecture--something you need to review.

- Get a blank sheet of paper and 3-4 colored pens.

- Write the topic in the center and circle it.

- Without looking at your notes, draw 4-6 main branches for the major sub-topics. Use keywords only.

- Now check your notes. Add any branches or sub-branches you missed. Draw cross-connections between related ideas on different branches.

- Tomorrow, try to redraw the map from memory. Compare with the original. Study what you forgot.

Do this for one topic per day for a week. By the end of the week, you will have a set of mind maps covering your most important material, you will know exactly which topics need more study, and you will have a concrete feel for whether mind mapping works for your subjects and your brain.

Track your mind mapping sessions alongside your other study habits to build consistency. If you find that your focus drifts during map creation, try pairing it with the Pomodoro Technique--one 25-minute Pomodoro is usually enough for one detailed mind map.

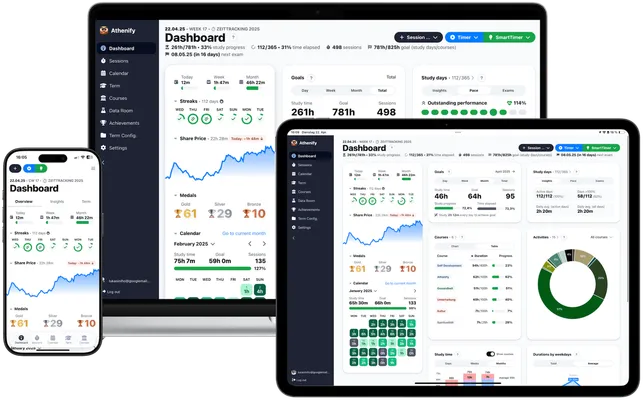

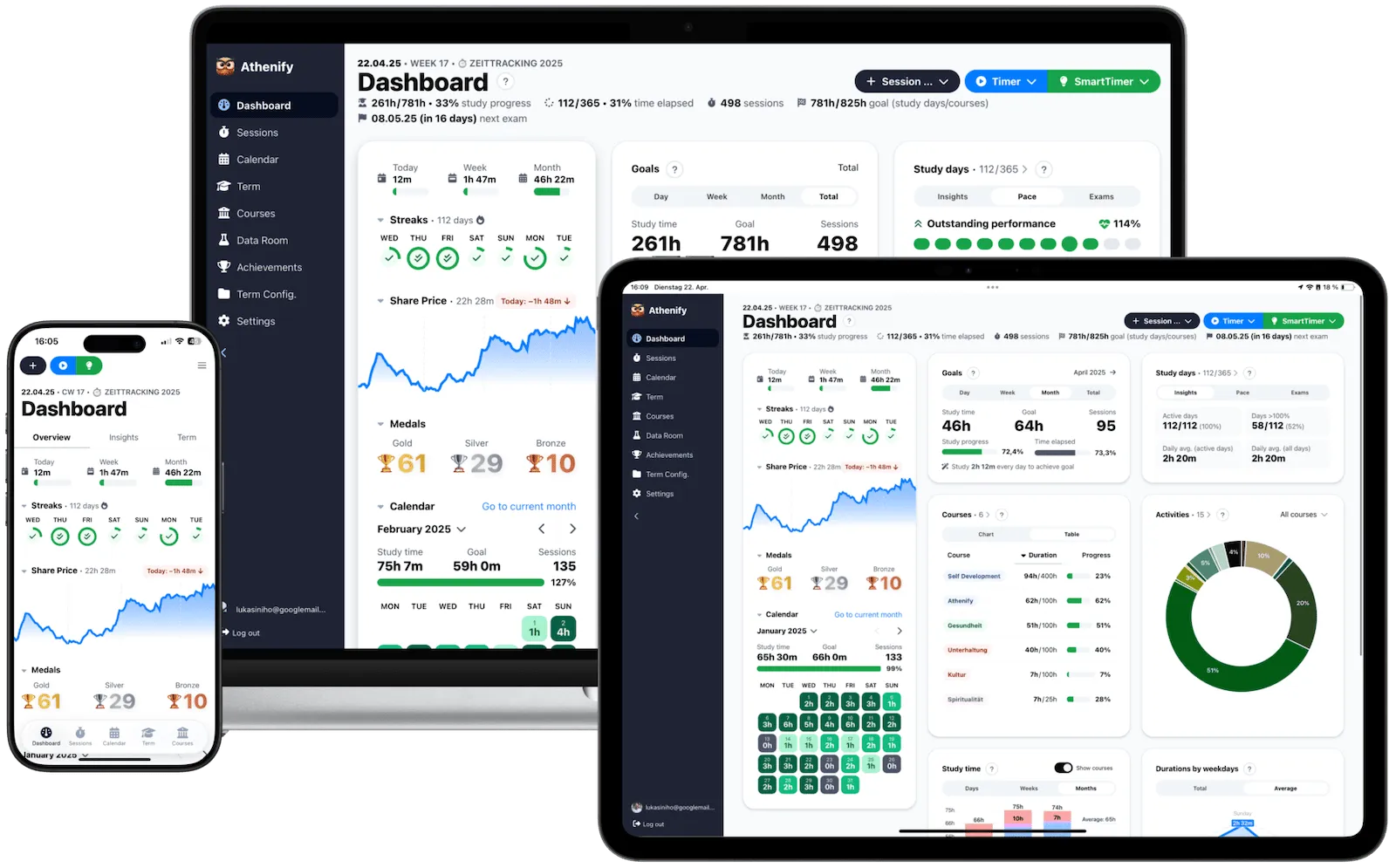

Try Athenify for free

Track your study sessions and see which techniques produce results. Build streaks, stay consistent, and study smarter.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Conclusion

Mind mapping is not a replacement for linear note-taking. It is a complement--a visual thinking tool that reveals connections your linear notes hide. The students who get the most from mind mapping use it strategically: for review and synthesis, for essay planning, for exam preparation, and for connecting ideas across courses.

Start small. One topic, one page, 15 minutes. Draw it by hand. Use color. Focus on connections, not completeness. Then test yourself by redrawing from memory. If you can reconstruct the map, you understand the material. If you can't, you know exactly where to focus your study.

The most powerful thing about a mind map is not what it shows you. It is what it reveals you don't know--yet.