The assignment is staring at you from your laptop screen. "Write a 4,000-word research paper on the economic impacts of climate change policy. Due March 1. Include at least 12 academic sources."

Your brain immediately translates this into: "This is enormous, vague, and will take forever. I don't even know where to start." And so you don't start. Not today, not tomorrow, not the day after. The assignment sits in your consciousness like a low-grade alarm, producing a steady hum of anxiety without ever triggering productive action.

The problem isn't your discipline, your intelligence, or your work ethic. The problem is that "write a 4,000-word research paper" isn't actually a task. It's a project containing dozens of tasks, and your brain can't engage with something that undefined. It's like being told to "build a house"--the instruction is technically clear, but you can't pick up a hammer and start without first knowing which wall to build, which brick to lay, which foundation to pour.

You don't procrastinate on small, clear tasks. You procrastinate on large, vague ones. Task chunking converts the latter into the former.

Task chunking is the systematic process of breaking any overwhelming assignment into pieces small enough that your brain can engage with them without resistance. It's not a productivity hack. It's a fundamental shift in how you approach work--and it's one of the most effective weapons against procrastination that exists.

Why your brain freezes on big tasks

To understand why chunking works, you need to understand why your brain chokes on large assignments.

The overwhelm response

When you contemplate a large, poorly defined task, your brain performs a rapid (and usually inaccurate) cost-benefit analysis. It estimates the effort required, compares it to your available energy, and if the gap feels insurmountable, it triggers an avoidance response. This isn't laziness--it's a protective mechanism designed to prevent you from wasting energy on tasks that seem impossible.

The key word is "seems." A 4,000-word research paper isn't actually impossible. It's probably 20-30 hours of work spread across several weeks. But your brain doesn't calculate that. It sees "4,000 words" and "12 sources" and generates a feeling of overwhelm that's disproportionate to the actual difficulty.

The specificity gap

Your brain can engage with specific, concrete actions: "Read page 47." "Write the first sentence of the introduction." "Search Google Scholar for three sources on carbon pricing." These are actions you can literally picture yourself performing.

But "write a research paper" isn't a specific action. It's a category of actions. Your brain can't picture "writing a research paper" because it contains too many sub-tasks, decision points, and unknowns. The vagueness itself is what triggers avoidance--not the difficulty.

Task chunking bridges this specificity gap by converting abstract projects into concrete actions.

How to chunk any assignment

Step 1: Define the final deliverable

Before you can break a task apart, you need to know what "done" looks like. Read the assignment prompt carefully and extract the concrete requirements:

- Format: Essay, report, presentation, problem set?

- Length: Word count, page count, number of problems?

- Components: Introduction, methodology, bibliography, appendix?

- Sources: How many? What type?

- Deadline: When is it due?

Write these down. This becomes your project specification--the target that your chunks will collectively reach.

Step 2: Identify the major phases

Every academic assignment follows a rough sequence of phases. Identifying these gives you the high-level structure for your chunks.

For a research paper:

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| Research | Finding and reading sources |

| Planning | Creating an outline and thesis |

| Drafting | Writing the first version |

| Revising | Improving structure and arguments |

| Polishing | Editing, formatting, citations |

For exam preparation:

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| Inventory | Identifying all topics to cover |

| Review | Rereading notes and textbook |

| Practice | Working through problems and questions |

| Consolidation | Creating summary sheets |

| Testing | Doing practice exams under timed conditions |

Step 3: Break each phase into 15-45 minute chunks

This is where the real work happens. Take each phase and break it into tasks that meet these criteria:

- Specific: You can picture exactly what you're doing

- Bounded: You know when it's done

- Achievable: Completable in a single sitting of 15-45 minutes

- Independent: Doesn't require completing another chunk first (where possible)

Here's an example of chunking a research paper on climate policy:

Research phase:

- Read assignment prompt and list all requirements (15 min)

- Search Google Scholar for 5 sources on carbon pricing (20 min)

- Search Google Scholar for 5 sources on renewable energy subsidies (20 min)

- Read and annotate source 1, extract key arguments (30 min)

- Read and annotate source 2, extract key arguments (30 min)

- Continue for each source

Planning phase: 7. Write a one-sentence thesis statement (15 min) 8. Create a bullet-point outline with section headers (20 min) 9. Assign sources to each section of the outline (15 min) 10. Write a detailed outline for the introduction (15 min) 11. Write a detailed outline for section 1 (15 min) 12. Continue for each section

Drafting phase: 13. Draft the introduction paragraph (25 min) 14. Draft section 1, paragraphs 1-3 (30 min) 15. Draft section 1, paragraphs 4-6 (30 min) 16. Continue for each section 17. Draft the conclusion (25 min)

Revising phase: 18. Reread full draft, mark areas that need improvement (30 min) 19. Revise the introduction and thesis clarity (20 min) 20. Revise section 1 for argument flow (25 min) 21. Continue for each section

Polishing phase: 22. Check all citations are properly formatted (20 min) 23. Proofread for grammar and spelling (25 min) 24. Format according to style guide requirements (15 min) 25. Final read-through, submit (20 min)

What was one terrifying task is now 25 manageable ones. None of them is overwhelming. Each one has a clear start point, a clear end point, and a realistic time estimate.

The discovery chunk: when you don't know where to begin

Sometimes you can't chunk a task because you don't understand it well enough. The assignment is vague, the subject is unfamiliar, or you genuinely don't know what the first step should be.

This is where the discovery chunk comes in: a small, time-bounded task whose only purpose is to clarify the larger project.

Examples of discovery chunks:

- "Spend 15 minutes reading the assignment prompt and writing down every question I have"

- "Skim the first 10 pages of the textbook chapter to understand the scope"

- "Watch the first 15 minutes of the lecture to identify key topics"

- "Email the professor with my three biggest questions about the assignment"

- "Search for two example papers to understand what's expected"

When you don't know where to start, start by figuring out where to start. That's a valid first chunk.

The discovery chunk is powerful because it transforms "I don't know what to do" (paralyzingly vague) into "I'm going to spend 15 minutes figuring out what to do" (concrete and achievable). The output of the discovery chunk is clarity, which enables you to create the rest of your chunks.

Chunking for different types of assignments

Chunking an essay

The key challenge with essays is that students try to write them linearly: introduction first, then body, then conclusion. This maximizes resistance because the introduction is often the hardest part to write.

Better chunking approach:

- Write the thesis statement (15 min)

- Create a bullet-point outline (20 min)

- Draft body section 1 (30 min)

- Draft body section 2 (30 min)

- Draft body section 3 (30 min)

- Draft the conclusion (20 min)

- Draft the introduction last (20 min)

- Revise for flow and argument coherence (30 min)

- Proofread and format (20 min)

Writing the introduction last is counterintuitive but highly effective. You can't introduce something you haven't written yet. By the time you've drafted the body and conclusion, the introduction practically writes itself.

Chunking exam preparation

Exam prep is uniquely well-suited to chunking because it naturally divides into topics. The challenge is ensuring comprehensive coverage without getting bogged down in any single area.

Chunking approach:

- List every topic that could appear on the exam (15 min)

- Rate your confidence on each topic: strong, medium, weak (10 min)

- Create chunks for weak topics first (highest impact)

- For each topic: review notes (15 min) + practice problems (20 min) + create summary card (10 min)

- End with a full practice exam under timed conditions (varies)

Spread the chunks across available days using a study schedule. Interleave topics rather than marathon-studying one subject per day--research on distributed practice shows this produces significantly better retention.

Chunking a group project

Group projects add coordination complexity on top of the normal challenges. Chunking helps by making each person's responsibilities explicit and bounded.

Chunking approach:

- Discovery chunk: read the assignment together and list all deliverables (20 min)

- Divide deliverables into individual chunks

- Assign chunks with clear deadlines and specifications

- Build in integration chunks: "Combine sections 1 and 2, check for consistency" (30 min)

- Build in review chunks: "Read the full draft and leave comments" (30 min)

The specificity of chunks prevents the most common group project failure: one person doing everything because roles were vague.

Pairing task chunking with other techniques

Task chunking defines what you do. These complementary techniques define how and when.

Chunking + the 2-Minute Rule

Once you've created your chunk list, apply the 2-Minute Rule to start the first one. The combination is devastatingly effective against procrastination: chunking removes the overwhelm, and the 2-Minute Rule removes the starting resistance. You've now eliminated the two biggest barriers to productivity in a single system.

Chunking + Pomodoro Technique

Each chunk maps naturally to one or two Pomodoro sessions. A 25-minute Pomodoro is the perfect container for a 15-25 minute chunk. For larger chunks (30-45 minutes), use two Pomodoros with a short break in between.

Chunking + structured procrastination

When you can't face the chunk at the top of your list, use structured procrastination to work on a different chunk instead. Because your chunks are independent and all contribute to the project, completing any chunk--not just the "right" one--moves you forward.

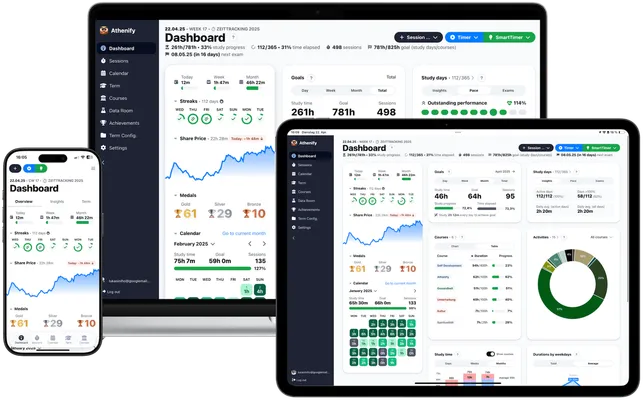

Chunking + time tracking

Track the time you spend on each chunk. This produces invaluable data: you'll learn how long different types of academic work actually take, which corrects the planning fallacy and makes future time estimates more accurate. After a few weeks of tracking, you'll know that "draft a 500-word section" takes you 35 minutes, not the 2 hours you feared.

Common chunking mistakes

Mistake 1: Chunks that are too vague

"Work on the essay" is not a chunk. "Draft paragraphs 2-4 of section 1" is a chunk. The difference is specificity. If you can't picture yourself doing the task in concrete terms, it needs to be broken down further.

Mistake 2: Chunks that are too small

Going too granular creates overhead. "Write sentence 1 of paragraph 3" is too small--the time spent managing your task list exceeds the time saved by chunking. Aim for the 15-45 minute sweet spot.

Mistake 3: Ignoring dependencies

Some chunks must happen in sequence: you can't "revise section 2" before "drafting section 2." When creating your chunk list, note any dependencies and ensure your schedule respects them. Independent chunks can be done in any order, which gives you flexibility on days when certain tasks feel more approachable than others.

Mistake 4: Never updating the list

Your initial chunk list is a first draft, not a final plan. As you work, you'll discover that some chunks take longer than expected, some can be combined, and some need to be split further. Update your list after each study session based on what you've learned.

The psychology of checking things off

There's a reason chunking works beyond pure logistics: completing a chunk triggers a small dopamine release. Your brain rewards you for finishing something, however small. This neurological reward creates a positive feedback loop--each completed chunk makes the next one feel more appealing.

Every checked box is a small victory. Stack enough small victories and the assignment that felt impossible becomes a trail of completed steps behind you.

This is why long, undefined tasks are so demotivating. With no intermediate completion points, your brain never gets the reward signal. You work for hours with nothing to show for it except "I'm still working on the paper." Chunking turns that experience into a series of wins: "I finished the outline. I drafted section 1. I revised the introduction." Each win energizes the next one.

For a complete system that eliminates procrastination from your study routine, combine task chunking with the morning routine strategies and motivation techniques covered in our other guides.

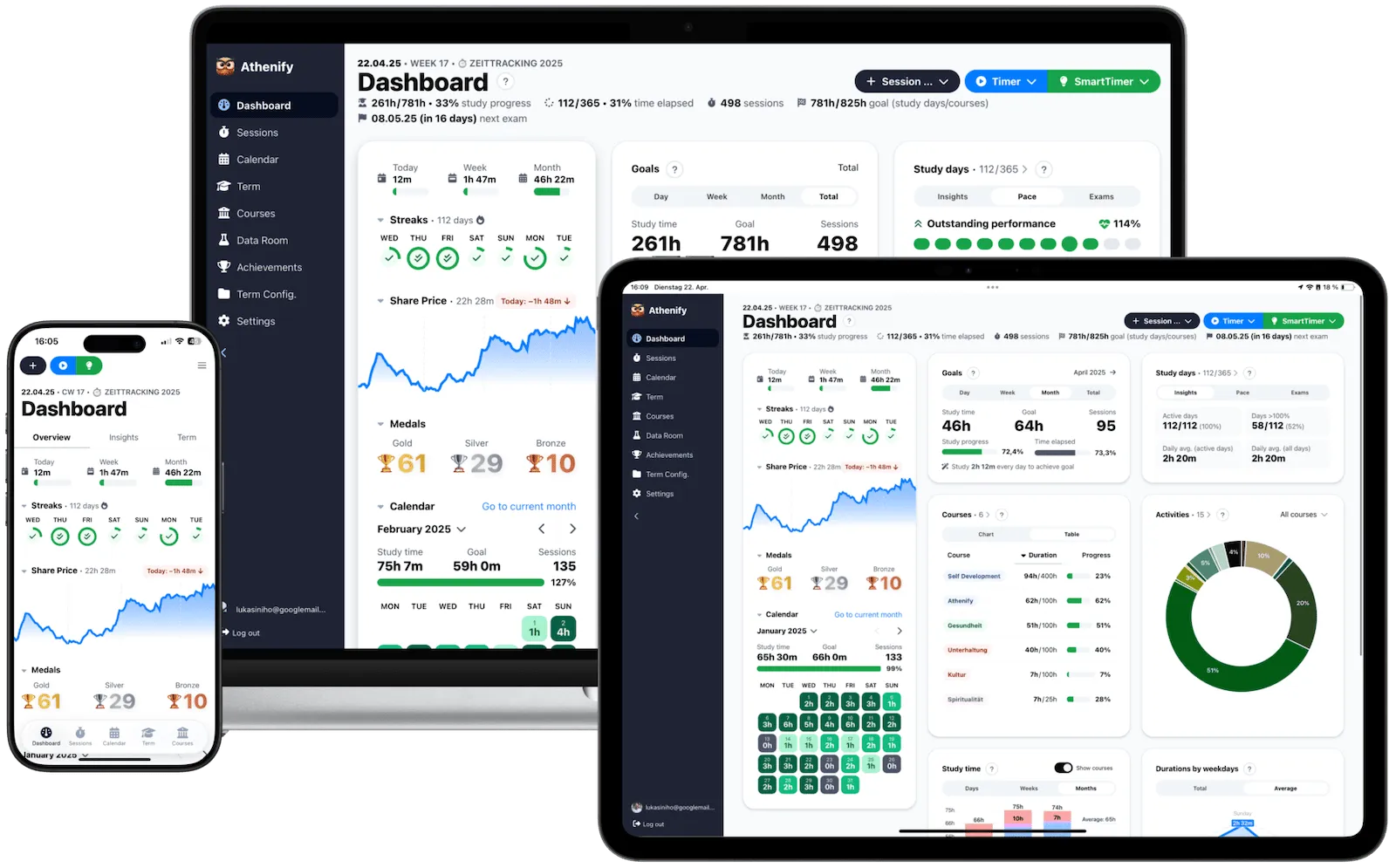

Try Athenify for free

Track the time you spend on each chunk. Athenify shows you exactly how long assignments actually take--so next time, you plan with data instead of dread.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Your first chunk starts now

Pick the assignment that's been looming over you. The one you've been avoiding. Open a blank page and write the following:

Assignment: nameDue date: dateFinal deliverable: what you need to submit

Now break the first phase into three chunks. Just three. Each one should start with a verb and take 15-45 minutes.

Then do the first chunk. Right now. Use the 2-Minute Rule if you need to--commit to just 2 minutes of the first chunk.

You don't need to see the whole staircase. You just need to take the first step.