You download a language app. You complete a few lessons. You feel like you're making progress. Six months later, you still can't hold a basic conversation. What went wrong?

This is the most common language learning story: initial enthusiasm, scattered effort, disappointing results. The problem isn't intelligence or talent—it's method. Most people study languages in ways that feel productive but aren't.

The difference between language learners who succeed and those who don't isn't time invested—it's how that time is used.

The good news? Decades of research have revealed what actually works for language acquisition. Here's how to study a foreign language using methods that produce real results.

The science of language acquisition

Before diving into techniques, it helps to understand how your brain actually learns languages.

Language acquisition happens through two complementary processes: explicit learning (consciously studying vocabulary, grammar rules, pronunciation) and implicit learning (absorbing patterns through exposure, the way children learn their first language). Both matter. Relying on only one produces lopsided results.

Explicit learning is efficient for building foundational knowledge quickly. You can learn 20 new vocabulary words in a single session. But explicit knowledge doesn't automatically transfer to real-time use—you need implicit learning to make language automatic.

Implicit learning happens through massive exposure to comprehensible input—language you can mostly understand with some new elements. This is where immersion shines. But without foundational knowledge, immersion can be overwhelming and inefficient.

"We acquire language in one way and only one way: when we understand messages. We call this comprehensible input."

— Stephen Krashen, linguist

The optimal approach combines both: use explicit study to build knowledge, then activate that knowledge through immersive practice.

Vocabulary acquisition: The foundation of fluency

Vocabulary is the raw material of language. Without words, you have nothing to work with—no amount of grammar knowledge helps if you don't know the words for what you want to say.

Focus on high-frequency words first

Here's a fact that should change how you study: the most common 1,000 words in any language cover approximately 80–90% of everyday speech. The next 1,000 words add only another 5–7%. This follows Zipf's law—a small number of words do most of the work.

This has profound implications. Learning obscure vocabulary (medieval weapons, specialized botanical terms) before mastering high-frequency words is wildly inefficient. Focus on the words you'll actually encounter.

A practical progression: start with the 500 most frequent words, which gives you enough for basic communication. Then expand to 1,000 words for everyday conversations. Push to 2,500 words for reading newspapers and native content. Finally, aim for 5,000+ words for near-native comprehension.

Use spaced repetition for vocabulary

Spaced repetition is the single most effective technique for vocabulary retention. Instead of cramming words and forgetting them, you review at strategically increasing intervals—just before you'd forget.

When creating flashcards, resist the temptation to use isolated words. Instead, put each word in context within a full sentence—"El gato duerme" teaches you more than just "gato = cat." Include audio pronunciation when available, because hearing the word correctly from the start prevents fossilized mispronunciations later. For concrete nouns, add an image; visual associations create stronger memory traces than translations alone. And create cards in both directions: recognition cards (target language → native) are easier but less useful; production cards (native → target language) are harder but mirror what you actually need to do when speaking.

Vocabulary learned in context sticks. Vocabulary learned in isolation floats away.

Learn words in context

Isolated word lists are the least effective way to learn vocabulary. Words learned in context—within sentences, stories, conversations—are remembered 3–5× better and are more accessible during actual use.

When you encounter a new word, don't just note its translation. Note the entire sentence. Note what situation it appeared in. Note related words that appeared nearby. This creates rich memory traces with multiple retrieval paths.

Grammar: Structure without obsession

Grammar is essential—it's the system that allows you to combine words into meaningful sentences. But grammar study is also where many learners get stuck, spending years memorizing conjugation tables without being able to speak.

The grammar-first trap

Traditional language education emphasizes grammar rules before communication. Students memorize verb conjugations, case endings, and agreement patterns—then struggle to produce a single spontaneous sentence.

The problem? Explicit grammar knowledge doesn't automatically transfer to implicit ability. You can know that German uses Subject-Object-Verb order in subordinate clauses while being unable to produce that pattern in real-time conversation.

Grammar should serve communication, not replace it.

A better approach to grammar

Learn patterns, not rules. Instead of memorizing that the subjunctive is used for hypotheticals, uncertainty, and wishes after certain conjunctions, learn example sentences that demonstrate the pattern. Your brain will extract the rule implicitly.

Focus on high-frequency structures first. Every language has grammatical structures that appear constantly and others that appear rarely. Master present tense before worrying about the past subjunctive.

Use grammar reference as a tool, not a curriculum. When you encounter a structure you don't understand, look it up. This just-in-time learning is more effective than front-loading grammar before you need it.

The four skills: Balancing input and output

Language proficiency encompasses four distinct skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Most learners dramatically over-invest in some skills while neglecting others—creating lopsided ability that feels frustrating in real situations.

Listening: The undervalued skill

Listening comprehension is often the weakest skill for self-taught learners. It's also the most important for real-world communication—you can't respond appropriately if you don't understand what was said.

You can't have a conversation if you can't understand what the other person is saying.

The challenge: spoken language is fast, reduced (sounds get swallowed), and unpredictable. Text-based study doesn't prepare you for this. The solution is massive listening practice with comprehensible input.

Graded listening resources (designed for learners at your level) are invaluable early on. Podcasts for learners, slow news broadcasts, and textbook audio provide the right level of challenge.

Native content becomes accessible as you progress. Start with content where you can see the speakers (movies, TV shows) since visual context aids comprehension. Use subtitles strategically: target language subtitles help connect sounds to words; native language subtitles are a crutch that prevents real listening practice.

Speaking: Active production

Speaking is where explicit knowledge becomes implicit ability—and it's the skill most learners neglect because it feels uncomfortable.

You cannot think your way to speaking fluency. You must speak—awkwardly, incorrectly, slowly at first—to develop the automatic production that fluency requires.

Conversation practice is irreplaceable. Language exchange partners (find them on apps like Tandem or HelloTalk), tutors (affordable on iTalki), or local conversation groups provide necessary practice opportunities.

Shadowing is a technique where you repeat what a native speaker says, matching their rhythm, intonation, and pronunciation. It builds the motor patterns needed for speech without requiring a conversation partner.

Self-talk works surprisingly well. Narrate your day in your target language. Describe what you see. Argue with yourself about decisions. This builds fluency without the pressure of a real conversation.

Reading: The vocabulary accelerator

Reading is the most efficient way to encounter new vocabulary in context. A single novel might expose you to thousands of unique words, many repeated enough for implicit learning.

Graded readers—books written specifically for learners at different levels—are underused but invaluable. They provide comprehensible input at your level, gradually introducing new vocabulary and structures.

Native content becomes accessible around the intermediate level. Start with genres you enjoy—motivation matters. Use a structured approach: look up unknown words that appear repeatedly (high-frequency unknowns), but don't stop for every unfamiliar word (this kills reading flow).

Writing: Cementing knowledge

Writing forces precision. When speaking, you can wave your hands, use filler words, avoid structures you don't know. When writing, you confront your gaps directly.

Journaling in your target language is an accessible daily practice. Write about your day, your thoughts, what you learned. Don't worry about perfection—the goal is production practice.

Get feedback when possible. Language exchange partners can correct your writing. Online tools like Lang-8 or Journaly connect learners with native speaker corrections. Active recall of correct forms after feedback accelerates improvement.

Immersion vs. structured study

The language learning community often polarizes between immersion advocates ("just move to the country!") and structured study advocates ("grammar and vocabulary drills are essential!"). Both extremes miss the mark.

The case for structured study

Structured study builds foundational knowledge efficiently. You can learn the 1,000 most common words in a few months of focused flashcard study—it would take years to encounter them all naturally in immersion. Grammar patterns that take 10 minutes to explain explicitly might take thousands of hours of exposure to acquire implicitly.

Structured study proves especially valuable in specific situations. Beginning learners benefit most because they have too little knowledge for immersion to be comprehensible—watching a Spanish movie when you know 50 words is mostly just noise. When you have specific weaknesses, targeted practice is far more efficient than hoping random exposure will cover your gaps. And time-constrained learners get more from 30 minutes of focused study than 30 minutes of undirected exposure, because every minute is optimized.

The case for immersion

Immersion provides what structured study cannot: real language as it's actually used. Native speakers don't speak like textbooks. They use idioms, contractions, cultural references, and pragmatic patterns that explicit instruction rarely covers.

Immersion becomes increasingly valuable as you progress. Intermediate and advanced learners have enough foundation to actually benefit from exposure—they can parse sentences and learn from context. For listening comprehension, there's simply no substitute for massive audio input; you need hundreds of hours of hearing the language spoken naturally. And for natural phrasing and fluency, immersion provides what textbooks cannot: the implicit patterns, idioms, and rhythms that make speech sound native rather than translated.

The optimal combination

Build knowledge through structured study, activate it through immersion. Use your target language for entertainment (shows, movies, music, podcasts). Practice conversation regularly. But also maintain your vocabulary review sessions and address specific weaknesses with targeted study.

Tracking progress and staying consistent

Language learning is a marathon, not a sprint. Progress can feel invisible over weeks, even months—which is why so many learners quit before reaching fluency.

Why tracking matters

Tracking your study time and activities creates accountability and reveals patterns. Without tracking, it's easy to overestimate effort ("I study every day!") while underestimating actual time invested.

What you track matters. Log your daily study time across different activities—not just total minutes, but where those minutes went. Track your vocabulary review completion, asking yourself honestly: did you actually do your flashcard reviews, or did you skip them? Monitor which skills you're practicing, because most learners unconsciously neglect listening or speaking while overinvesting in comfortable reading. And log your native content consumption: hours of listening, pages read. These immersion hours compound over time in ways that structured study alone cannot replicate.

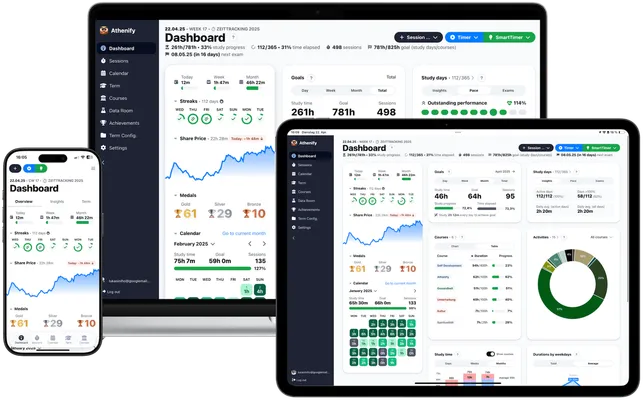

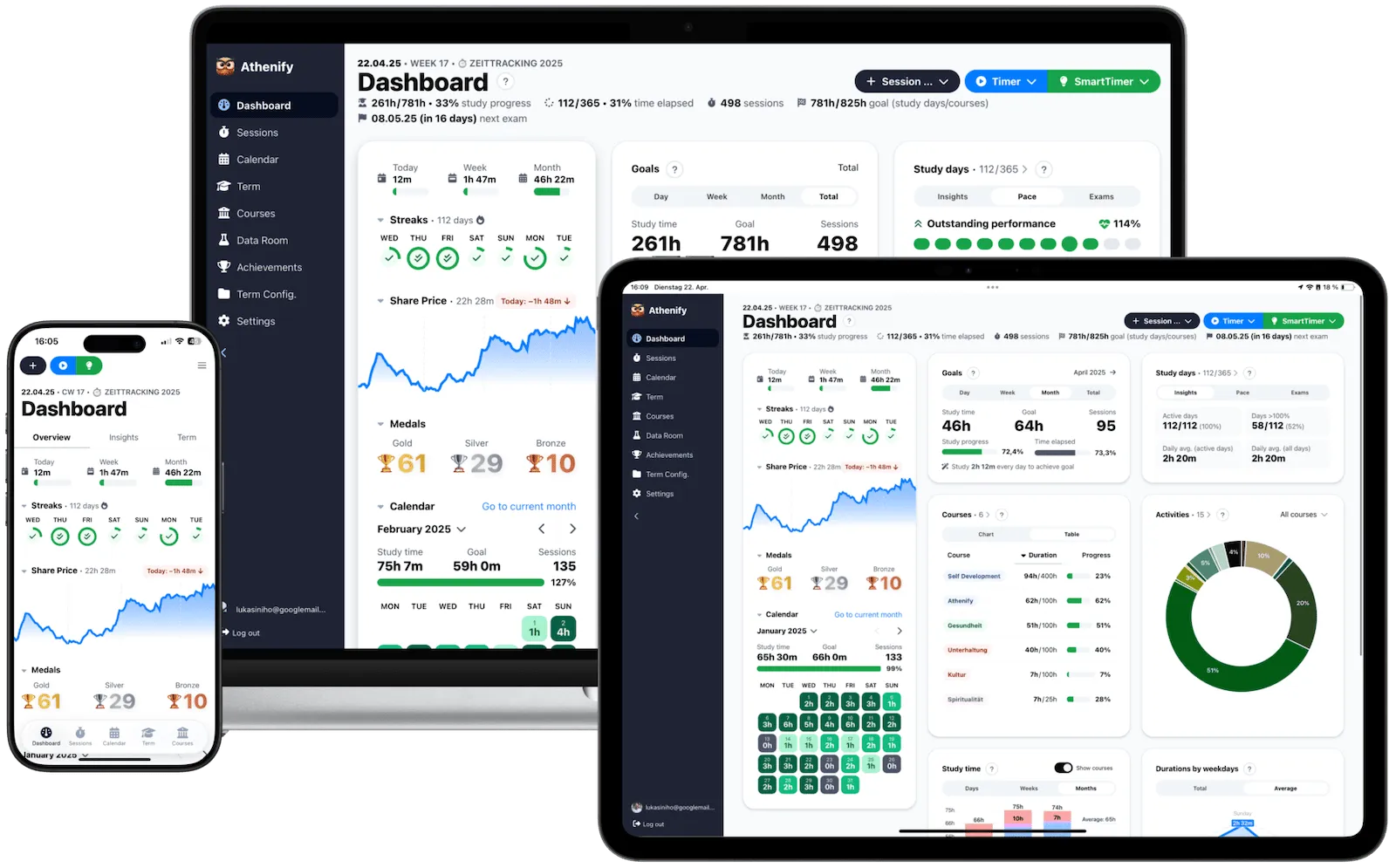

Tools like Athenify make tracking effortless—start a timer when you begin, stop when you finish. The study timer helps maintain focus during dedicated study blocks.

Try Athenify for free

Track your language learning sessions, see which skills need more attention, and build streaks that keep you accountable.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

The consistency principle

Frequency beats intensity. Thirty minutes daily produces far better results than three hours on weekends. Your brain consolidates language during sleep—daily exposure gives your brain daily opportunities to reinforce what you've learned.

Language learning is a daily habit, not an occasional project.

Aim for daily contact with your target language, even if some days are minimal (a 5-minute flashcard review still maintains the habit).

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Mistake 1: All input, no output

Watching shows and reviewing flashcards feel productive and comfortable. Speaking feels uncomfortable and exposes gaps. So learners do more of the former and avoid the latter.

The result: comprehension far outpaces production. You understand conversations but can't participate in them.

Fix: Schedule non-negotiable speaking practice. Even 15 minutes of conversation practice three times weekly dramatically accelerates progress.

Mistake 2: Perfectionism paralysis

Waiting until you're "ready" to speak, write, or consume native content. Avoiding mistakes rather than learning from them.

Fix: Embrace imperfection. Errors are data, not failures. You will sound ridiculous at first. Everyone does. That's how learning works.

Mistake 3: Tool hopping

Constantly searching for the "perfect" app, textbook, or method. Spending more time researching how to learn than actually learning.

Fix: Pick a reasonable method and commit for at least three months before evaluating. No method is perfect, and switching constantly prevents any method from working.

Mistake 4: Neglecting pronunciation early

Pronunciation patterns are hardest to change after they've solidified. Learners who neglect pronunciation early often plateau with an accent that's difficult to understand.

Fix: Work on pronunciation from the beginning. Learn the sound system explicitly. Use shadowing to develop native-like patterns. Record yourself and compare to native speakers.

Mistake 5: Studying about the language instead of using it

Reading grammar explanations, watching videos about learning, discussing method—without actually practicing the language.

Fix: Most of your time should be spent using the language: speaking, listening, reading, writing. Studying about the language is a small supplement, not the main activity.

A practical study plan

Here's how to structure your daily practice for balanced progress:

Your daily essentials should take 30–45 minutes. Spend 15–20 minutes on vocabulary review using spaced repetition flashcards—this non-negotiable maintenance keeps your word bank growing. The remaining 15–20 minutes go to listening practice: podcasts, shows, or audio content at your level. These two activities form the backbone that everything else builds on.

Your weekly additions add another 3–5 hours of deeper practice. Aim for 2–3 conversation practice sessions of 30 minutes or more—this is where passive knowledge becomes active ability. Dedicate 1–2 hours to reading, starting with graded readers and progressing to native content as your skills allow. Include 2–3 short journaling sessions in your target language; writing forces precision that speaking allows you to avoid. Grammar review happens as needed, targeting specific weaknesses you've identified rather than following a textbook's predetermined sequence.

Your monthly assessment keeps you on track. Review honestly what's working and what isn't—which activities feel productive versus performative? Adjust your time allocation based on weak skills; if speaking lags behind reading, shift hours accordingly. Set specific, measurable goals for the next month so progress becomes visible.

Explore more study techniques that complement your language learning routine.

Conclusion: The path to fluency

Fluency isn't a destination you arrive at—it's a direction you travel in, one day at a time.

Learning a foreign language is achievable for anyone willing to invest consistent effort using effective methods. The core principles are clear: master high-frequency vocabulary first using spaced repetition, because 1,000 words cover most daily speech. Balance all four skills—listening is often neglected but critical for real communication. Combine structured study with immersion: build knowledge explicitly, activate it through exposure and use. Track your progress and study daily, because consistency beats intensity every time. And avoid the common traps: passive consumption, perfectionism paralysis, and method-hopping.

The students who reach fluency aren't more talented—they're more strategic. They use their study time on what actually works and maintain the daily habit long enough for compound progress to accumulate.

Start today. Review your first flashcards. Listen to your first podcast. Have your first awkward conversation. The path to fluency begins with a single study session.