You read the chapter. You highlight the formulas. You nod along to the examples. Then you open the problem set and stare at question one like it's written in ancient Sumerian. What went wrong?

You fell into the most common trap in mathematics education: confusing recognition with ability. Understanding an example when it's explained to you is not the same as being able to solve a problem yourself. In math, more than almost any other subject, the gap between watching and doing is vast.

You don't learn math by watching someone else do it. You learn math by doing it yourself.

This guide covers everything you need to know about studying mathematics effectively. These are proven study techniques backed by cognitive science and refined by generations of successful math students.

Why most students struggle with math

Before diving into techniques, let's understand why math feels uniquely difficult—and why traditional study approaches fail.

The cumulative knowledge problem

History is additive: you can learn about World War II without understanding Ancient Rome. Math is cumulative: you cannot understand calculus without algebra, and you cannot understand algebra without arithmetic. Every gap in your foundation becomes a crack that widens as you advance.

This is why students often hit a "math wall" at some point in their education. They've been accumulating small gaps—a concept not quite understood here, a procedure memorized without comprehension there—until suddenly the gaps are too large to bridge without going back.

"Mathematics is not about numbers, equations, computations, or algorithms: it is about understanding."

— William Paul Thurston, Fields Medalist

The passive learning trap

Most students study math the same way they study other subjects: they read, they highlight, they review notes. But math doesn't yield to passive approaches.

| Passive approach (ineffective) | Active approach (effective) |

|---|---|

| Reading worked examples | Attempting problems first |

| Highlighting formulas | Deriving formulas from memory |

| Watching lecture recordings | Solving problems while paused |

| Re-reading textbook sections | Teaching concepts out loud |

| Reviewing solution steps | Explaining why each step works |

When you read a worked example, your brain follows along and thinks "This makes sense." But following is not the same as leading. On an exam, no one leads you through the steps. You have to generate them yourself—and that's a completely different cognitive process.

The fundamentals of effective math study

1. Work problems before looking at solutions

This is the single most important principle for studying math. Before you look at any worked example or solution, attempt the problem yourself.

Even if you fail—especially if you fail—the struggle primes your brain to understand the solution more deeply when you see it. You've already identified what you don't know, so when the explanation arrives, it fills a gap you're aware of.

The problem-first method starts with reading the problem carefully, then attempting a solution without looking at notes or examples. When you get stuck—and you will—that's actually good. Identify exactly where your understanding breaks down. Only then should you look at the solution or example, not just reading it but genuinely understanding why each step works. The crucial final step that most students skip: close the solution and try the problem again from scratch. Only when you can solve it without reference should you move to a similar problem and repeat the cycle.

2. Use active recall for formulas and concepts

Active recall—testing yourself on material without looking at your notes—is just as crucial in math as in other subjects. But in math, it takes specific forms.

For formulas, don't just read them over and over. Cover the formula and try to write it from memory—the struggle to recall strengthens the memory trace. Whenever possible, derive the formula from first principles; understanding where it comes from means you can reconstruct it when memory fails. For each variable, make sure you can explain what it represents and why it appears in that form. Finally, apply the formula to a problem without referring to it. If you can't use it without looking, you don't really know it.

A formula you can derive is a formula you'll never forget on exam day.

For concepts, use the "explain it simply" test. Can you explain the chain rule to someone who's never heard of it? Can you describe why we use integration by parts? If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it deeply.

3. Build mathematical intuition, not just procedure

Many students learn math as a collection of procedures: "When you see this type of problem, do these steps." This works until it doesn't—usually on exams with unfamiliar problems.

Real mathematical understanding means knowing why procedures work, not just how to execute them. When you understand the why, you can adapt to novel problems and catch your own errors.

Building intuition requires a fundamental shift in how you engage with material. After every step, ask "why does this work?" rather than just "what's next?" This single question, asked consistently, transforms superficial understanding into deep comprehension. Connect new concepts to ones you already understand—mathematics is a web of relationships, and isolated facts are fragile while connected knowledge is robust. Visualize problems graphically whenever possible; a picture can reveal structure that equations hide. Look for patterns across different problem types, because recognizing similarities is how mathematicians transfer techniques. And when you encounter a theorem, don't just memorize it—understand the proof. The proof reveals the logic that makes the theorem true.

4. Master one concept before moving on

Math's cumulative nature means rushing ahead creates compounding problems. If you sort-of-understand something, you'll definitely-not-understand what builds on it.

Before moving to the next section, make sure you can:

- Solve problems without looking at examples or notes

- Explain the concept clearly in your own words

- Recognize when to apply this concept in novel contexts

- Connect it to previous material

Specific techniques for math mastery

Spaced repetition for formulas

You need to memorize certain formulas—there's no way around it. But cramming before exams leads to rapid forgetting. Spaced repetition, where you review material at increasing intervals, creates durable memory.

Implementing spaced repetition for math starts with creating flashcards for key formulas—digital apps like Anki work particularly well because they automate the spacing intervals. On one side of each card, put the name of the formula or a problem that requires it. On the other side, include the formula itself plus a brief explanation of when to use it. Review daily at first, then at increasing intervals as you master each card—this is the "spaced" part that makes retention stick. Crucially, don't just create "what is the formula?" cards. Include "why does this work?" questions that test your conceptual understanding, not just your memorization.

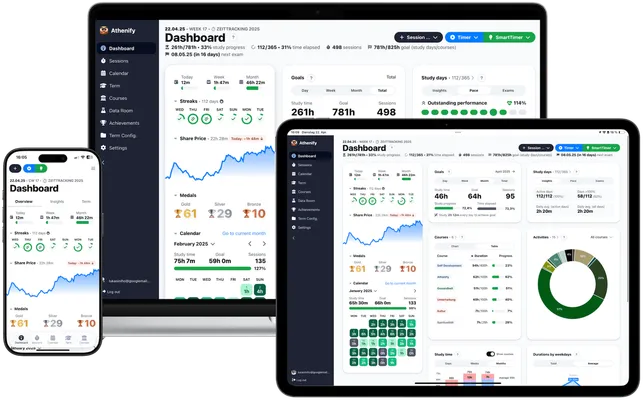

Use tools like our study timer to structure your practice sessions and track consistency.

The worked example–problem pair method

Research shows an effective learning sequence: study a worked example, then immediately solve a similar problem without looking back.

- Study a worked example carefully—understand each step and why it's taken

- Close the example immediately

- Solve a similar problem from your problem set

- Check your solution—not just the answer, but each step

- Analyze any differences between your approach and the example

- Repeat with a harder variation

The goal isn't to mimic procedures. It's to internalize principles.

Error analysis: Learn from every mistake

Mistakes in math are not failures—they're data. Every error tells you something about your understanding or process. The students who improve fastest are those who analyze their mistakes systematically.

When you get a problem wrong:

- Don't just look at the correct answer—understand why your answer was wrong

- Classify the error: Conceptual misunderstanding? Computational slip? Misread the problem?

- Trace back: Where exactly did your solution diverge from the correct path?

- Make a note: Keep an "error log" of common mistake patterns

- Create a problem: Write a new problem that tests the same concept

Teaching and explaining

The best way to confirm you understand something is to teach it. When you explain a concept, you're forced to organize your knowledge, identify gaps, and think about it from a fresh perspective.

Explain problems out loud, step by step, as if teaching someone who knows nothing about the topic. The act of verbalizing forces you to organize your thoughts and expose hidden confusions. Study with a partner and take turns being the "teacher"—the one explaining learns more than the one listening. Write out explanations of concepts in your own words, without looking at your notes. When you stumble in your explanation, you've found exactly where your understanding needs work—that's a feature, not a bug.

Structuring your math study sessions

The Pomodoro Technique for math

Math requires sustained concentration, but your brain can only maintain deep focus for limited periods. The Pomodoro Technique provides ideal structure:

- Choose a specific topic or problem set

- Set a timer for 25 minutes

- Work with complete focus—no distractions

- Take a 5-minute break (stand up, stretch, hydrate)

- After four cycles, take a longer 15–30 minute break

Daily vs. weekly math study

Consistency beats intensity. Daily 45-minute practice sessions build stronger neural pathways than weekend cramming marathons. Your brain needs time between sessions to consolidate learning.

Recommended schedule:

- Daily (45–60 min): Work new problems, review previous material using spaced repetition

- Weekly (2–3 hours): Tackle harder problems, connect concepts across sections

- Before exams: Practice tests under timed conditions, review your error log

What to do when you're stuck

Getting stuck is part of math. The question is how you respond.

If you've been stuck for less than 10 minutes, the struggle is still productive. Reread the problem carefully—did you miss something in the wording? Try a completely different approach; often the first method that comes to mind isn't the best. Draw a diagram or work through a simpler version of the problem. Check whether you're even using the right formula or concept—sometimes the issue is choosing the wrong tool.

If you've been stuck for more than 10 minutes, it's time to seek targeted help. Look at a hint—but not the full solution. Review the relevant concept in your notes or textbook to shore up gaps in understanding. Sometimes the best move is to set the problem aside, work on something else, and return later with fresh eyes. And there's no shame in asking for help from a teacher, tutor, or study group—this is what they're for.

Common math study mistakes to avoid

Mistake 1: Practicing only easy problems

It feels good to solve problems quickly. But if you're never struggling, you're not learning. Growth happens at the edge of your ability.

Fix: After warming up with easier problems, always push into territory that challenges you.

Mistake 2: Looking at solutions too quickly

Every time you peek at the answer early, you lose the chance to strengthen the neural pathways that produce solutions.

Fix: Enforce a minimum struggle time. Set a timer for 10 minutes before you're allowed to check hints.

Mistake 3: Focusing on answers instead of process

Getting the right answer by the wrong method, or by lucky guessing, teaches nothing.

Fix: Always verify your process matches the correct solution, not just the final answer.

A correct answer with a flawed process is more dangerous than a wrong answer you understand.

Mistake 4: Skipping steps when writing solutions

Rushing through notation and skipping "obvious" steps leads to errors and hidden misunderstandings.

Fix: Write out every step, especially while learning. Clarity in your written work reflects clarity in your thinking.

Mistake 5: Studying math like you study literature

Reading a math textbook like a novel doesn't work. Math is a contact sport—you learn by engaging, not spectating.

Fix: Have paper and pencil ready whenever you're reading math. Work every example yourself before reading the solution.

Building long-term mathematical confidence

Reframe your relationship with struggle

Many students interpret difficulty as evidence they're "not a math person." But struggle is the point, not the problem. Every mathematician, at every level, experiences regular confusion and frustration.

"If you're not confused, you're not learning."

— Common saying in mathematics education

The difference between successful math students and those who give up isn't innate ability—it's their response to difficulty. Growth happens when you push through confusion, not when you avoid it.

Track your progress

Progress in math can feel slow, especially when you're deep in challenging material. Tracking your study time and problem completion helps you see improvement that might otherwise be invisible.

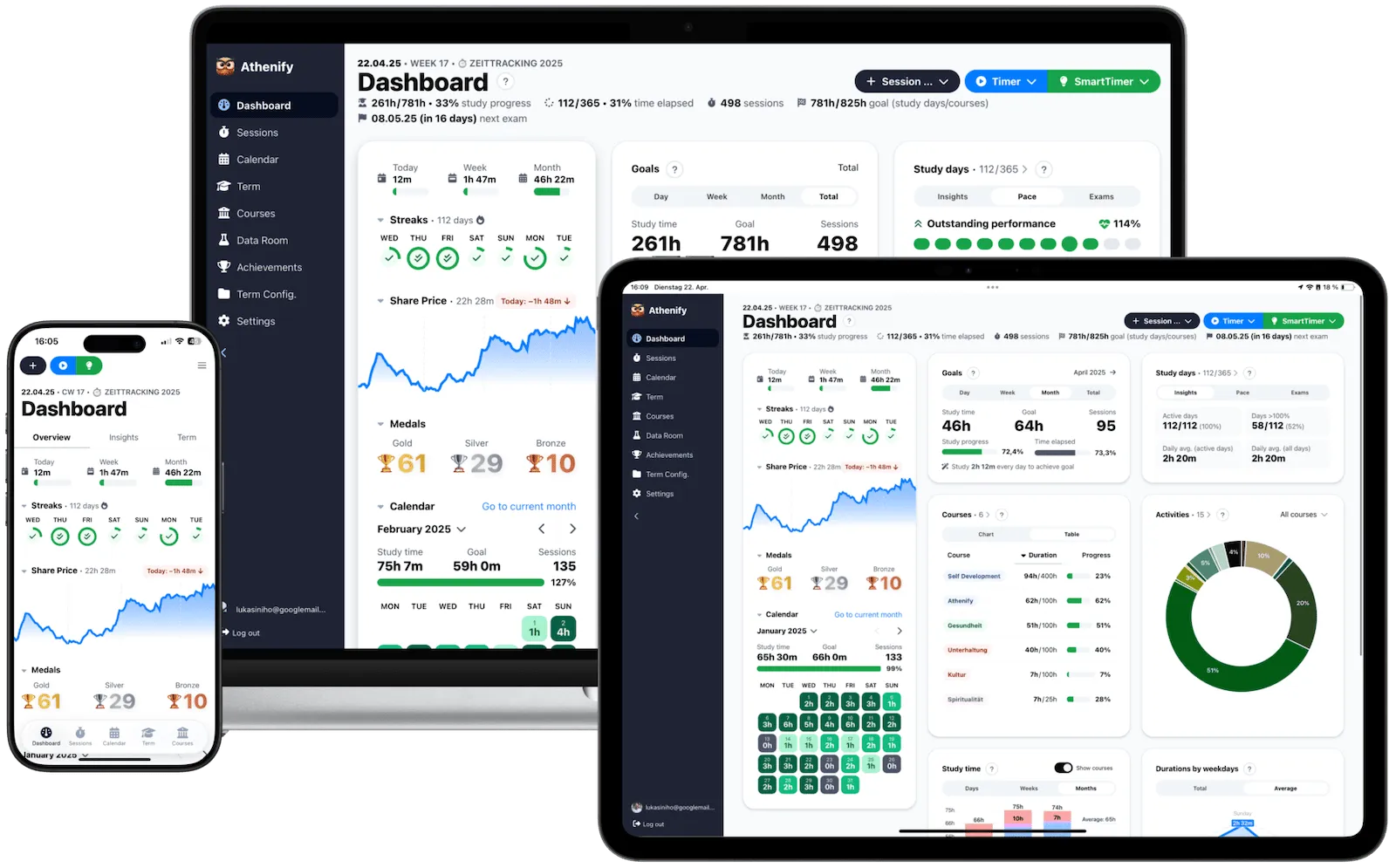

Use tools like Athenify to log your study sessions. Over time, you'll see patterns: how many problems you're completing, which topics need more attention, whether you're maintaining consistency.

Try Athenify for free

Track your math study sessions, build consistency with streaks, and identify which concepts need more practice.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

Connect math to meaning

Abstract math becomes easier when connected to applications you care about. Physics, economics, computer science, biology—nearly every field uses mathematics as its language.

When studying a new concept, ask: "Where is this used in the real world?" Understanding applications provides motivation and often deepens conceptual understanding.

Conclusion: Math mastery through deliberate practice

Mathematics is not a spectator sport. You don't learn by watching—you learn by doing.

The path to mathematical competence is straightforward but demanding. Work problems before looking at solutions—the struggle is where learning happens. Use active recall for formulas, testing yourself rather than re-reading. Build intuition by asking "why" at every step, not just "how." Master each concept before moving forward, because math's cumulative nature punishes gaps.

Structure your sessions with time-boxing techniques like Pomodoro, and prioritize consistency over intensity—daily 45-minute sessions beat weekend cramming. When you make mistakes, treat them as learning opportunities: analyze them, categorize them, and create problems that test those weak points.

Most importantly, reframe your relationship with difficulty. Every mathematician struggles. The students who succeed are those who push through confusion rather than running from it. Mathematical ability isn't something you're born with—it's something you build, one problem at a time.