You've probably been told you're a "visual learner." Or an "auditory" one. Maybe you've even taken one of those tests that explained, with colorful graphics, how your brain supposedly works. That's nonsense. Not slightly oversimplified, not "roughly accurate"—scientifically debunked for over 15 years. The learning styles theory belongs in the same category as horoscopes: it sounds plausible, feels personal, and is completely baseless.

The problem isn't just that learning styles are wrong. The problem is that they cause harm. They lead people to limit themselves, waste time, and ignore study methods that actually work. Yet 93% of teachers still believe in the myth. Time to set the record straight.

What learning styles claim

The idea originated with Frederic Vester (1975) and became internationally known through Neil Fleming's VARK model (1987). The core claim is simple: people can be categorized as visual (learns through images), auditory (learns through listening), kinesthetic (learns through movement and touch), and sometimes reading/writing as a fourth category. Know your type and study accordingly, the theory goes, and you'll learn more effectively.

The theory has intuitive appeal. Of course you have preferences—maybe you prefer reading to listening, or you like diagrams more than walls of text. But here's the fundamental flaw: preference is not effectiveness. You might prefer chocolate to broccoli. That doesn't make chocolate healthier. Similarly, your preference for videos doesn't mean you learn better from videos than from text.

Preference is not effectiveness. You prefer chocolate to broccoli—that doesn't make it healthier.

The scientific debunking

What the research actually shows

In 2008, Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, and Bjork published a comprehensive meta-analysis in Psychological Science in the Public Interest. They reviewed all available literature on learning styles and asked a simple question: Is there evidence for the so-called meshing hypothesis? This hypothesis is the core of learning styles theory—the claim that learning outcomes improve when instruction matches the learner's "type."

"We found virtually no evidence for the meshing hypothesis."

The result was devastating. The few studies that even had proper methodology—randomized assignment, measurement of actual learning outcomes rather than just satisfaction—consistently showed: It makes no measurable difference whether instruction matches the supposed learning style or not. Visual learners don't learn better from images; auditory learners don't learn better from podcasts.

The research didn't stop with Pashler. Willingham, Hughes, and Dobolyi confirmed the findings in 2015 in "The Scientific Status of Learning Styles Theories." Rogowsky, Calhoun, and Tallal tested explicitly in 2015 whether "visual learners" learn better from books and "auditory learners" learn better from audiobooks—the result was negative. Husmann and O'Loughlin examined anatomy students in 2019 who studied according to their VARK results and found no correlation with exam performance.

Why the myth survives anyway

If the evidence is so clear, why do so many people still believe? The answer lies in the psychology of the myth itself:

- Intuitive appeal: Everyone has preferences, so they must be important—or so the reasoning goes.

- Flattering effect: "You're a visual learner!" provides identity, an explanation for difficulties, sometimes a convenient excuse.

- Profitable industry: Learning style tests, workshops, books, online courses—millions are spent on these annually.

- Entrenched in training: Many educators learned about learning styles as established knowledge.

- Confusion with real concepts: Multimodal learning—using different sensory channels—actually works. But it works for everyone, not type-specifically. This confusion keeps the myth alive.

Why learning styles cause harm

The myth isn't just wrong—it actively causes harm. Someone who believes they're an "auditory learner" might tell themselves: "I can't learn from books." This isn't just false; it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. You try less, get worse at it, and "confirm" your belief. This self-limitation is especially tragic because it's based on fiction.

Add to that wasted time. Hours spent converting study material into your supposed "type"—recording everything as audio or drawing everything as diagrams—would often be better invested in evidence-based methods. And while you're wondering "Am I actually a kinesthetic learner?", you're missing techniques that demonstrably work.

A particularly problematic aspect: sometimes students are labeled "kinesthetic" when they actually have attention issues or other challenges. The label distracts from real solutions and delays appropriate support.

What actually works

The good news: there are study techniques that genuinely work—supported by dozens of studies, replicated over decades, effective for all people regardless of supposed "types." Combine these methods with solid study habits, and you'll maximize your learning efficiency.

- Active Recall: Test yourself instead of passively reading

- Spaced Repetition: Distributed practice with increasing intervals

- Interleaving: Mix different topics instead of working through blocks

- Elaboration: Actively connect new knowledge with prior knowledge

- Dual Coding: Combine words and images

These methods work for everyone—no learning types required.

Active recall and spaced repetition

Active recall means testing yourself instead of passively reading. You close the book and ask: "What did I just learn?" This simple act of retrieval strengthens neural connections.

Roediger and Karpicke showed in 2006 that students who tested themselves retained significantly more than those who only reviewed. This works with flashcards, self-tests after each chapter, fill-in-the-blank exercises, or explaining to others.

Closely related is spaced repetition—distributed practice with increasing intervals. Instead of cramming everything in one day, you review material across days and weeks, ideally just before you'd forget it. The spacing effect was discovered by Ebbinghaus back in 1885 and is one of the most robust findings in learning psychology. Apps like Anki use algorithms to calculate optimal review intervals.

Interleaving and elaboration

Interleaving means mixing different topics or problem types instead of completing one topic entirely before moving to the next. In math, this means mixing different problem types in one session. In languages, it means alternating between grammar, vocabulary, and reading. The brain learns to distinguish between different concepts and retrieve the right knowledge at the right time—a skill that's crucial in exams. Our guide on deep work with Athenify explains how to integrate these methods into focused study blocks.

Elaboration means actively connecting new knowledge with existing knowledge. You ask: "Why is this the case? How does this relate to what I already know?" You search for analogies, find real-life examples, create mind maps. The more connections you create, the more retrieval pathways emerge—and the more resistant the knowledge becomes to forgetting.

Dual coding—for everyone

Dual coding means combining verbal information with visual representations: drawing diagrams alongside texts, creating sketchnotes, using infographics. This works because your brain stores verbal and visual information in different systems. When both work together, more retrieval pathways emerge.

Dual coding doesn't mean "visual learners" need images—it means all people learn better when words and images work together.

Here's a common misconception: Dual coding is often misunderstood as proof of learning styles. But the opposite is true. Dual coding is a universal principle—it works for everyone, not just supposedly "visual" learners. The combination of words and images helps the auditory learner just as much as the visual one, because it's based on the fundamental architecture of human memory.

Multimodal learning: Why variety works for everyone

Here's the key that's often misunderstood: Using different sensory channels actually works—but not because you're a certain "type." It's a universal principle.

The brain is not a learning type. It's a multimodal processing system that benefits from variety.

When you read about a topic, watch a video about it, explain it to someone, and then do practice problems, you learn better. Not because you happened to serve all "types," but for entirely different reasons:

- Different perspectives deepen understanding

- Spacing effect—repetition in different formats leverages this effect

- Active processing—explaining and practicing is more effective than passive absorption

- Dual coding—the combination creates more neural connections

The content determines the medium—not your "type." You learn anatomy with images because the structures are visual. Languages require listening and speaking because language functions auditorily. Programming requires practice because skill comes through doing. That's about the subject, not about you.

Data over gut feeling

If learning styles don't work—what then? The answer is simpler and simultaneously more demanding than a personality test: Experiment and measure.

The real individual differences in learning:

- Prior knowledge – How much you already know about the subject

- Motivation – How interested you are in the topic

- Working memory capacity – How much you can process simultaneously

- Self-regulation – How well you manage your learning

You can influence and improve these factors—unlike a supposedly innate "type."

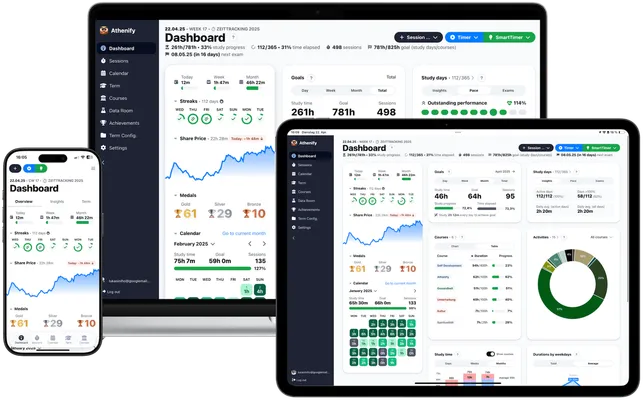

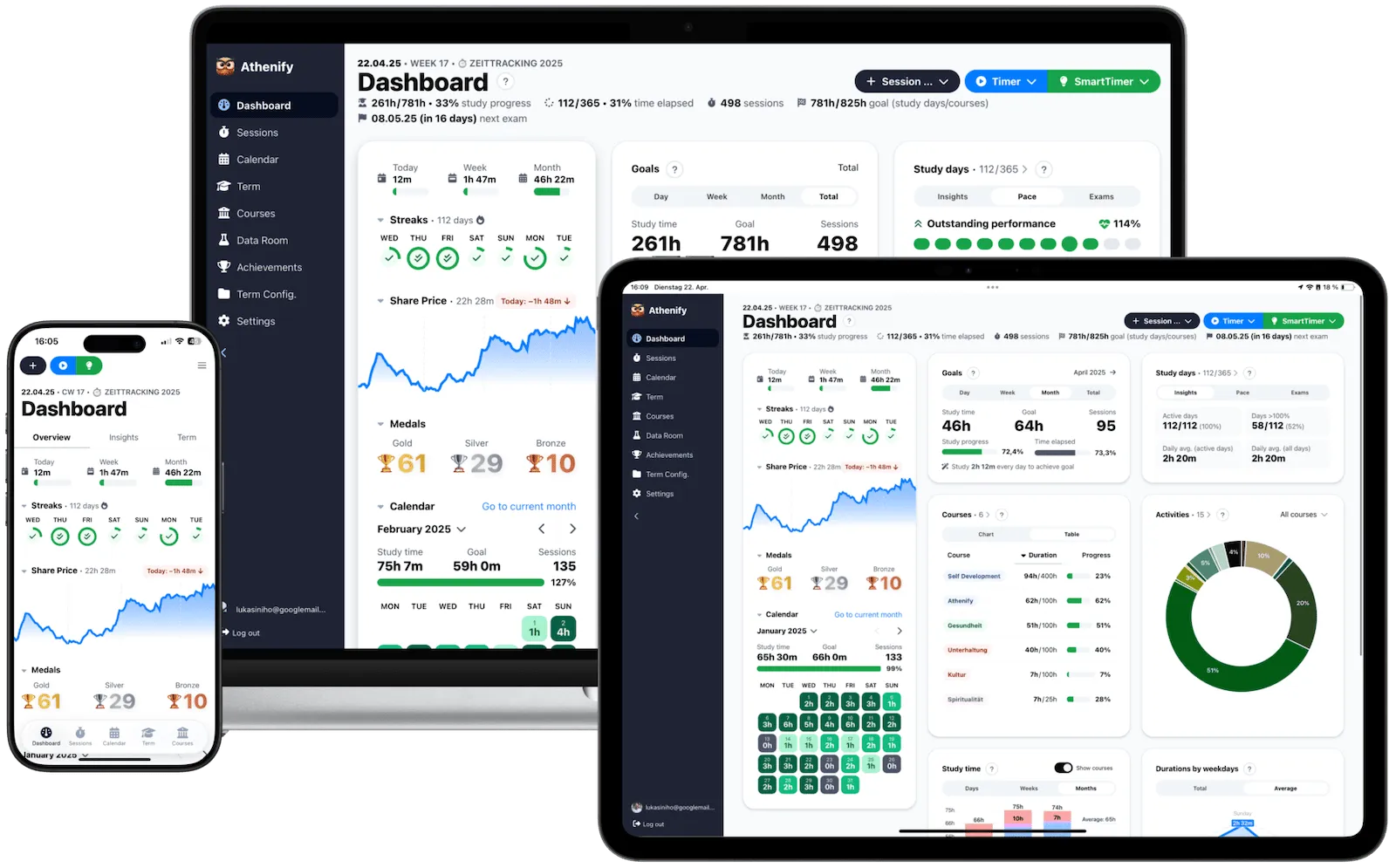

Try Athenify for free

Forget learning style tests—instead track which study methods actually work for you. Data over gut feeling.

No credit card required.

No credit card required.

With Athenify, you can track different learning activities—flashcard practice, problem sets, videos, writing summaries—and compare after the exam: Which subjects went well? How did you study for those subjects? The data reveals patterns your gut feeling misses. Maybe you learn better in the morning than evening. Maybe you need longer breaks. Maybe Pomodoro works for math but not for essays. These are real, individual differences—and you find them through data, not a learning style test.

Instead of asking "What type of learner am I?", ask: "Which method works for me in this subject, at this time, under these conditions?" You find the answer through systematic experimentation and honest measurement—not through self-assessment in an online quiz.

Conclusion: Science over myth

Learning styles are a myth—and a harmful one at that. The research has been clear for over 15 years: there's no evidence that people fall into fixed learning types or that type-matched instruction works better. The myth leads to self-limitation, wasted time, and distraction from methods that demonstrably work.

What actually works, works for everyone: active recall, spaced repetition, interleaving, elaboration, and dual coding are universal principles, not type-specific tricks. Real individual differences exist—but they lie in prior knowledge, motivation, and self-regulation, not in sensory preferences.

Stop labeling yourself as a "visual learner" or "auditory type." Start trying evidence-based methods—and measure the results. No pseudoscience. Just data.